Thank you to the Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies for granting permission to the Park Warden Service Alumni to post this interview on our website

Park Warden Alumni Society of Alberta

Oral History Project Phase 8 – Summer 2018

Telephone Interview with Marvin Millar

Interviewed by Christine Crilley-Everts

July 24, 2018

Place and Date of Birth: Wilkie, Saskatchewan. May 10, 1948.

Occupations: Before being sent to the Beaufort Sea as a federal fisheries technician, Marv applied for a warden position in Jasper National Park. In 1971, he began his career with the service working as the district warden in the Lower Smokey. After working as the Backcountry Coordinator and assistant chief in Jasper, Marv accepted a position at the Fortress of Louisbourg National Historic Site. From the east coast, Marv moved to prairies to take over as the Backcountry Coordinator in Riding Mountain National Park. He then became the Chief Warden and later took on a lead role for Parks Canada in the bovine tuberculosis outbreak around the park. Marv retried from Parks Canada in 2006 after 35 years of service.

Additional Information: Marv and his wife Diane keep very busy in retirement, spending their summers in the Yukon where Marv helps local outfitters and their winters in Arizona. They share a love of family, wilderness, and animals, especially horses and dogs.

Marv Millary, John Steele, Toni Klettl. Photo courtesy of Terry Damm

“The interviews are going to go to the Whyte Museum in Banff, to the archives there.”)

(1:10) Well you know…I couldn’t have asked for a better career. So I said I’m going to leave a bit of a legacy before I can’t remember it! Okay, let’s go at er!

“What is your date and place of birth?”

(1:34) May the 10th, 1948 and I was born in Wilkie, Saskatchewan.

“Is that where you grew up?”

Yep, I grew up on a farm. When I finished high school, I went to the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon. I spent two years in the University and then I transferred to the (what) was called the Kelsey Institute (Saskatchewan Polytechnic) and that’s where I spent two years in the Renewable Resource Diploma Program and graduated in about…1968/1969. I think is when I graduated from that college! From there I started, I was a Fisheries Technician. A federal Fisheries Technician in the Northwest Territories for two seasons, one in Hay River and one in Yellowknife. My third year in 1970, they were going to send me way into the Beaufort Sea on some fishery/mining thing and I didn’t really want to go there.

(2:54) So the next thing you know, I see these ads in the Edmonton Journal looking for park wardens…I didn’t know much about the national parks at that time…so I said I will try…they were looking for guys in Jasper. I applied on it and went for an interview, I don’t know where, in Edmonton somewhere? Bud Armstrong, was the Chief Warden (for) Jasper and he interviewed me in May of 1971 or something. A month later I was hired in Jasper and I started in the backcountry of the Lower Smokey District…

“That would be a nice place to start.”

(3:52) Yeah, well it was interesting. They were big districts back there and I had a little bit of horse experience, not a heck of a lot. Brian Wallace was my mentor and Al Stendie. Brian was at Willow Creek and Al was at Blue Creek and then I was in the Lower Smokey which is just north of Mount Robson there. It’s a beautiful part of the world.

(4:24) So I rode with Brian for about, I don’t know, 10 days or so. Then he turned around and left me and my four horses to go and continue on! I was the Lower Smokey warden for about four or five years…they moved guys around a bit, so I ended up at Willow Creek for a couple of years. Then I became the Backcountry Coordinator after about six or seven years…for the north boundary…that was for the summer…I worked in the backcountry from May until hunting season was over, until October or November. Then we would skidoo supplies in or whatever else for part of the winter. About four or five years later, I starting doing that in the summertime and then I’d work at the ski hill at Marmot Basin in avalanche control for the winter. I did that for probably five or six years. It was the perfect job! You rode horses all summer and skied all winter. I mean what else could a young man want? I did that for about five or six years. (Then I) moved from there to be the district warden at Pocahontas at the east gate. I was at the east gate for about three years, I guess and then I went back into the town site. I can’t remember for sure, but I think by then I became the Assistant Chief Warden.

(6:37) As I was going through my formative years Mac Elder, Ole Hermanrude, Toni Klettl, Bob Haney, Duane Martin, they were all my mentors. Or our mentors, for the young guys that were just kind of growing up. Those guys were real mentors, I mean they lived and died (for) the warden service. They grew up ‘hard, rode hard and put away wet’ lots. I guess that’s what a lot of us were like actually, you know. Whether it was after hours or during hours, we played hard, but we worked hard sort of a thing…

Marv Millar, Tom Davidson. Photo courtesy of Terry Damm.

(7:20) Just kind of giving you an overview there, I was in Jasper until 1985. Then for some reason I thought that maybe I should branch out a bit. I was there for 16 years or something, that I should try another park…it was quite easy to do. If you wanted to transfer whether you were at the same level, or promotions were the easiest way to transfer. But lots of times we would transfer back and forth at the same level in different parks, which was a good thing because you got to see different administrations and different organizations and how they did things. So it was a growing experience…

(8:07) I really wanted to go to Kootenay, so I applied. I had to go against Peter Whyte and he kicked my ass in an interview! I placed second or third, but you might as well place a hundred rather than second if there is only one job! Then I resigned to the fact that maybe I am not Chief Warden material and I would just stay in Jasper. The next thing you know there are some jobs on the east coast. The Fortress of Louisbourg came open and it was at the same level. It was in a historic park, so it was kind of a different experience…I applied on that position and low and behold I won the competition! So we packed up our family, we had two kids…our kids were ten and seven, our daughter was ten and our son was seven in Jasper. I said, “Listen kids, we are going to move to the east coast.” Well, the kids essentially hated me (for) taking them away from their school and from their friends. We moved to Louisbourg and lived there for about three or four years, I can’t remember exactly…It was different because it was a historic park. So I’m used to being in a park that is 4000 square miles and I’m in one that is ten square miles! I could walk across the park in a day and there was nothing to do. It was mainly looking after the historic artifacts. The Environmental Assessment Review Program was really strong because of all the artifacts. You know every time you did anything you were digging up some artifacts from the 1700s…French or British artifacts – they were shooting at each other. And we were responsible for all the fire suppression on the fortress. The (fire suppression system) was built in, I don’t know when, in the 60s, so the fire suppression stuff…all the hydrants and everything else were all from the 60s…I said this is the only place that is surrounded by water and is going to burn to the ground someday, because if you put any pressure on these hoses on the lines they would inevitably break…

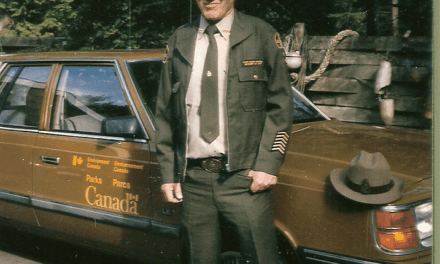

Marv Millar. Photo courtesy of Terry Damm

(10:53) Anytime we had a chance, we had a camper and we would tour Nova Scotia, PEI and Newfoundland and we really got to know the east coast…but we wanted to get back into the horses, we really liked horses…I knew Ray Frey from Jasper. He was the Chief Warden of Riding Mountain at the time. He phoned me, Keith Foster was moving somewhere and he said, “I am going to have a vacant, Backcountry Coordinator position here.” He said, “You might think about applying for it…” So we hummed and hawed a little bit and the next thing you know, we (decided that we) could try it out. And I happened to win that competition. Now my kids are 14 and ten and we are moving them from the east coast. Now they hated me again because I am taking them away from their friends and from their school and we move to Riding Mountain. It was a sort of neat dichotomy and actually it’s interesting because now both my kids live in Nova Scotia.

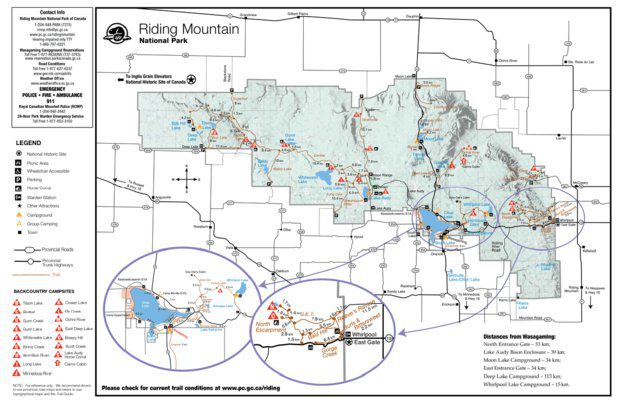

(Wikipedia describes Riding Mountain National Park (French: Parc national du Mont-Riding) is a national park in Manitoba, Canada. The park is located within Treaty 2 Territory and sits atop the Manitoba Escarpment.[2] Consisting of a protected area 2,969 km2 (1,146 sq mi),[1] the forested parkland stands in sharp contrast to the surrounding prairie farmland. It was designated a national park because it protects three different ecosystems that converge in the area; grasslands, upland boreal and eastern deciduous forests. It is most easily reached by Highway 10 which passes through the park. The south entrance is at the townsite of Wasagaming, which is the only commercial centre within the park boundaries.)

It’s just the value that the national parks was able to give me, to give us. You know, we spent their first formative years in the mountain parks, then to the east coast and then we went to a prairie park in Riding Mountain and the kids graduated from high school there and went off to colleges…then they both chose to move to the east coast and they are still there…that’s where they are making their lives and their families. They are maritimers now! So that is the value of what the national parks gave me and I think it gave a lot of people that option. You got to see all sorts of different places and of course national parks being what they are, they are probably the most pristine places in any province. So when you get the opportunity to move from one to the other you have an influence on (how) your family turns out and where they want to live and this kind of stuff. Now my kids are maritimers and I never would have thought that in a million years! They could have stayed in Jasper their whole lives…but they were able to pick and choose because they saw, the prairie life, the ocean life and the mountain life, and they chose the ocean life.

(13:37) Then my first wife and I got divorced in Manitoba. I raised my kids through kind of a tough few years. Ray Frey was a super (guy) to have as a Chief Warden, he really helped me out and kept me on the straight and level. Then when he retired, I applied on the Chief Warden job in Riding Mountain and I won that competition. Then I was the Chief Warden of Riding Mountain. In 2006, I retired as the Chief Warden of Riding Mountain…

(15:21) Some people really had an influence on me. Willi Pfisterer being one…My father passed away in 1980 and I think Willi lost his son Freddy somewhere in there…Willi was really heartbroken about losing his son and I had lost my father, both of us had a loss there. He sort of became my father almost. I could talk to him about anything. He was always such a true honest individual. He really was a good person and he really influenced the way that I thought I should be as an adult as I was growing up and that kind of stuff…

Marv Millar and John Steele. Photo courtesy of Terry Damm.

(16:38) We’d be going on these mountaineering trips, Brian Wallace and I were on some kind of advanced school…we were on Mount Collin in Jasper. It was a very sheer face that we were climbing. Brian and I and there were a couple of others guys, I think Clair Israelson or Gerry (Israelson) was with us too. Anyways, Brian and I end up on a little wee cliff. There was a blade of grass almost on a little precipice and both of us had our foot on that little piece of grass and we looked at each other and we said, “What the hell are two farm boys used to standing in 200 acres of wheat (doing) trying to survive on a little piece of a ledge where there is one blade of grass growing?” We were on ropes and everything else, but if somebody was to slip, we would have gotten seriously hurt. And Willi’s up on top and he says, “Hurry up you two! You guys go on ahead and I will meet you up top!” It was that humor that we were always able to use to get through tough times. Lots of times, there was a smart remark that would get you over the hump to make you push yourself a little bit farther and harder or whatever you know? I will never forget that time that we were on that little cliff and this little wee blade of grass there! Two farm boys there, we were a little bit out of our element!

(18:23) I was in Riding Mountain the last few years when things were starting to fall apart (as) they reorganized and had the Eco System Secretariat and whatever else. Paul Hanson was the Manager of Eco System Secretariat and I was the Chief Warden and when they reorganized those things, they made it into resource conservation or something, I can’t remember what we were called. But anyways…(because) Paul had his master’s degree and whatever else and he was in it for the long haul and I was kind of at the twilight of my career, he became the Manager of Resource Conservation and I was left holding the bag wondering what I was going to do?

(19:20) At that time we had just found out that there were some farmers (who had cattle infected with bovine tuberculosis). (Bovine Tuberculosis (BTb) is a contagious bacterial disease caused by Mycobacterium bovis. This long lasting, eventually debilitating disease can infect a number of mammals depending on the location. In Canada, it has been reported in bison, moose, deer, elk and cattle.) Riding Mountain…was an island of wilderness in a sea of agriculture…it’s so true, I mean there’s farmland right up to the park boundary and then there’s wilderness you know. Of course, the elk go back and forth and they graze out in the farmer’s fields and eat the farmer’s hay. The farmers shoot the elk and chase them back into the park. So…there’s quite a relationship there between the farmers and the wardens.

(20:10) Anyhow, some of these farmers, especially on the north side of the park, there were three of them, who ended up with bovine tuberculosis in their cattle herd. Bovine tuberculosis became very infectious to wild animals, the elk being one…it is a disease that is transferred via saliva and it sustains itself in 40 below weather and is transferred in straw or grain or wheat or hay. These elk would go out and eat these farmers hay in the field. The farmers would leave their hay out in the fields all winter lots of times. So the elk would go out there and eat these hay bales, then the bales would be taken in and fed to the cattle and somehow bovine tuberculosis got into the elk herd. So now we had an issue where the CFIA (Canadian Food Inspection Agency became) very heavily involved when these cattle herds became infected with bovine tuberculosis. It was 100% eradication, so if you had 200 cows…you’d get paid some compensation but your cows were all dead…now these farmers and the municipalities blamed the elk (for) giving it to the cattle. Well, if it’s called bovine TB, but it didn’t matter. If you lost your herd of cattle (it was devastating). I was very sympathetic to anybody who had (that happen). So now there was a lot of pressure on Riding Mountain to get rid of our elk. Well, we are in an ecosystem. We are a little different, we don’t do that stuff in national parks. I became the manager of that program to try and liaise with the land owners and the provincial people and the CFIA and the municipal governments around the park. I became the point man from Riding Mountain to do something then. To Parks Canada’s credit, they gave us a lot of money to try to do research and to do all sorts of things to try to get that the damn disease out of the elk the best we could. We had a few years, 2002 to 2004, before I retired, we probably euthanized 250 elk sort of thing then. We’d catch them with a helicopter and a net gun, take a blood sample, put a radio collar on the elk and then send the blood sample to the University of Saskatchewan lab and they would do the testing on it. If it came back positive at all then we went back in with the radio transmitter to find that elk and then we would take that elk out. So you can imagine, the costs that were involved were huge with this program.

(23:33) Of course we had to have these public meetings all around the park…it seemed like every two weeks, I had to go to a public meeting and give them an update as to what was going on…In the meantime…the CFIA was testing every farm and all their cattle around the park. So between the federal veterinarians and us, the farmers were really upset with government. The federal government mainly and the provincial government as well because they were involved in this thing, but it wasn’t quite as pronounced as the two federal parties, the CFIA and Parks Canada. So (as I said) for two years, it seemed like every second week, I was going to another public flogging basically and being blamed for everything that happened on these farms.

(24:50) One thing that we did do was that we continued that research program and they are still doing it, I think? We ended up getting a half a million dollars that we were able to give to each farmer. We hired a crew of First Nations people and they would build an eight-foot hay enclosure for free on each farmer’s property wherever he wanted. All he had to do was make sure that he kept those damn gates closed to keep the elk out of there! Actually, it seemed to work pretty good…I think we put up 300 fences over the course of a couple of seasons. They were good sized fences, they were probably worth, ten thousand dollars and so they got them for free. Parks Canada really did a lot of things to try and help alleviate the problem.