Thank you to the Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies for granting permission to the Park Warden Service Alumni to post this interview on our website.

This Oral History interview was funded in part by a research grant from the Government of Alberta through the Alberta Historical Resources Foundation

Park Warden Service Alumni Society

2020 Oral History Project Phase 10

Phone Interview with Wes Olson

Date/time March 28th, 2020 @ 1000

Interviewed by Monique Hunkeler

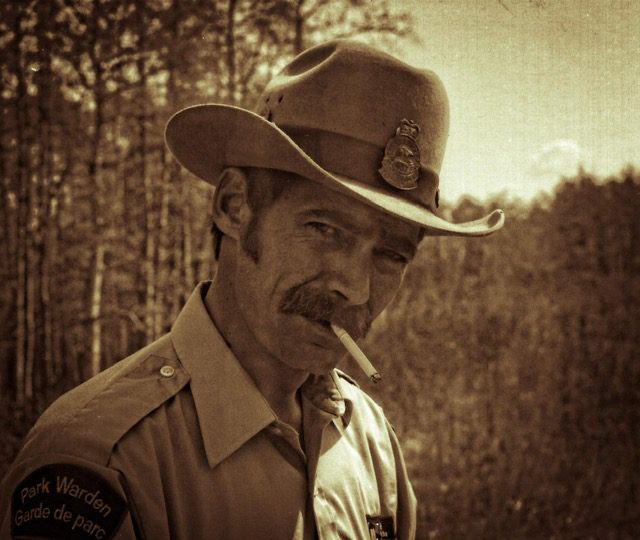

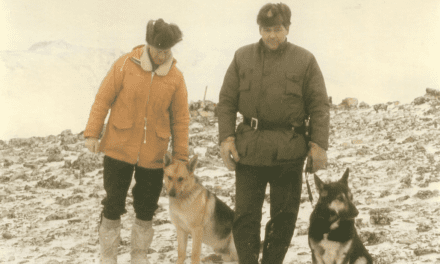

Wes Olson with Scout & Taiga 1999 in Elk Island National Park

Place and date of birth? I was born in Edson, Alberta, June 8th 1954

MH: Where did you grow up?

WO: My dad was a driller on the oil rigs so for the first six years, we moved all over the Province from one well-site to another but when school time came, we settled in Black Diamond, that’s where I grew up.

MH: How did you become involved in the Warden Service? Which national park did you start working in?

WO: It was not my initial career goal. I still have a grade 4 essay that I wrote about “What you want to do when you grow up” and it describes exactly how I spent the last 60 years. At that time, my father was a good friend with a provincial forest ranger and at that time, the forest rangers had virtually the same role as the generalist Park Warden job. I knew him well and I knew what he did, but over time, their role changed and became split into the various functions. I went to Lethbridge Community College and graduated from their Outdoor Conservation Program and started to work initially as a Forest Ranger but because they split their roles it no longer appealed to me but the Warden Service did. That’s how I got started with Parks. I started in Banff National Park in 1981.

MH: What made you want to join the Warden Service? 0220:

WO: Pretty much what I just described above. Prior to joining Parks after graduating from college, I worked for six years as a Wildlife Technician in the Yukon and Northern Alberta. This was mostly contract work and I got tired of that unpredictable lifestyle. So I started looking around and coincidentally at the same time, there was a competition for a Park Warden job, so I applied on it and managed to sneak my way in.

MH: What different parks did you work in? How did they compare? Do you have a favorite? 1135:

WO: I started in Banff as a term Warden in the fall of 1981, and moved to Waterton to a seasonal position in 1983. I stayed there for one season, went back to Banff for a 2-year term and then transferred to Elk Island National Park where I spent 24 years. The opportunity came along to go to Grasslands National Park in 2008, so we took it and spent 4 years working in Grasslands. I retired in 2012, and after 10 years living in Val Marie, we moved to a new acreage, near Elk Island, a couple of years ago.

0340: You know they are all totally different. People frequently ask what your favorite park was, and I don’t think I can nail it down to one, because they all had aspects that were really great. Of course, they had issues, like there is everywhere. Grasslands surprised us. I’d never lived or worked in a grasslands environment and it is amazing how it captivated both my wife and I. We still think of Grasslands (National Park) as one of our favourite parks just because it was so completely different than anything I’d done before. My position in Banff was doing Environmental Impact Assessments and I did lots of surveys of wildlife around the Banff townsite in the early 80s, so all my work with Parks to that point had been resource-based. Waterton was primarily Public Safety and Law Enforcement so that was hugely enriching for my career. Elk Island was a National Park where Wardens went to get their resource experience and most people came for two years and moved on to somewhere else. It is, and remains, a fascinating place for wildlife.

MH: What were some of your main responsibilities over the years? 0700:

WO: Mostly entirely Resource Management based. I did a little bit of Law Enforcement and Public Safety but over my 24 years, it didn’t account for much. There were a few rescues and the usual weekend drunks in the campground type stuff, a few poaching cases, but this did not account for a large part of my job.

For most of my career, I worked with bison in Elk Island, re-establishing bison populations across the historic ranges of both Plains and Wood bison. That’s what occupied the bulk of my career. They hired me back out of retirement to work on the reintroduction of bison into Banff National Park. It was a great experience. I was taking bison from Elk Island to everywhere from Russia to the United States and every time I would open the door of a trailer to release the animals into a new landscape, it felt like I was taking them from their home to a strange place. But for some reason, when we opened the doors to release them in Banff, it felt like we had brought them home, rather than taking them from their home. I can’t describe why that is. It was a completely different feel when they settled in and adapted to Banff National Park.

MH: What did you like / dislike about being a warden? 0920

WO: The diversity of it. You never knew from one day to the next what you were going to wake up and be tasked with doing. I think that is the key. With the old school warden service, we were responsible for everything from wildlife management to people and everything in between, and this was really rewarding. I personally didn’t care for the switch to the functional system and had no intention or desire to go into Law Enforcement.

What didn’t I like? 0200 in the morning wake up calls to go deal with a drunk. We did routine Public Safety work, car accidents, and backcountry rescues. But really for the bulk of my career, there wasn’t much that I didn’t like. Every job has its ups and downs but for the most part, the Warden Service had more ups than downs.

MH: What were some of your more memorable events as a Warden? 1100:

WO: Probably the one that comes to mind was relocating bison from Elk Island into Central Siberia. Flying in the belly of a huge Russian cargo plane, sitting down in the cargo hold with them for 36 hours. That was a unique experience. The plane was big enough that we loaded three horse trailers with 10 animals each, into the belly of the cargo plane. Elk Island shipped four loads from Elk Island over there, and I was on the first shipment. All North American Bison evolved from the species that lived in Asia and Siberia, that came across the Bering land regions of North America. The ones in Russia went extinct so they settled on bringing Wood Bison back. Genetically, they looked at the DNA of the bison that had been there and Wood Bison were virtually the same, so they are the ones we reintroduced. It was successful, the animals are doing very well. The release site is equivalent to about 200 Km north of Yellowknife in latitude. They get on the average probably 6 weeks of minus 60 Celsius and 100 centimeters of snow so it’s a harsh environment. They do not have reproductive rates like the populations in Canada, but the population is still increasing in size.

MH: Can you tell me about any rescue/wildlife stories that stick out in your memory? 1300:

WO: Because I spent the bulk of my career working with bison, that’s where most of my examples come from. I got a call one night about 02:00 in the morning from Jasper Dispatch, who connected me to a call in Edmonton. A very frantic mother was worried about her teenage daughter, who had gone hiking in Elk Island with a new boyfriend and hadn’t come home. So, my wife and I went out to see if we could find them. It was late in the fall and freezing at night, but no snow yet. I loaded up an all-terrain vehicle, drove from parking lot to parking lot until we found their vehicle, and then unloaded and went down the trail where they had gone. We found them sitting about 20 feet up in the tree, surrounded by a group of bison. They’d been walking on the trail and finding themselves surrounded by a herd, the boyfriend did his role of protecting his new girlfriend, by putting her up a tree and climbing up after her. We gave them a ride back to their car, called mom and she was very relieved.

We had a fair number of rescues like that, people were just getting stranded or lost. Most of my wildlife-related stories revolve around injuries to people or to myself. We were handling elk one day, as the parks had to remove the surplus of bison and elk from the park. It was winter and we had a large holding pen set up. My job on that day was to chase the elk from the holding pen, down an alleyway and into the corral system, where we would process them. The usual routine required two Wardens on foot, who would split the big herd of elk into groups that were manageable, chase them down this alleyway on foot and as soon as they went around a corner, a gate operator would close a gate and the handling would proceed.

On this occasion, the elk went around the corner but in doing so they kicked up enough snow so the gate operator couldn’t get the gate closed. But I couldn’t see that. The whole adrenalin of chasing elk on foot quickly dropped and you just relax and stop. I heard somebody yell ”look out” and I looked up and there were all these elk coming right back at me. The lead cow was off the ground when she hit me in the face and chest with her chest, and carried me backwards onto the frozen ground – knocked me out and 13 other animals went stomping and kicking overtop as she went past me. I ended up with a bunch of bruises, broken ribs and a concussion. That was unpleasant. But surprisingly, I’ve worked on over 50 large-scale bison capture and handling operations, and 20-30 large-scale elk handling operations, and we had very few injuries.

1647: Have you spoken with Angela Spooner? She was a Warden here in Elk Island and various national parks. She’s not with parks anymore but lives on Vancouver Island. Very attractive woman with these big brown eyes that really sucked you in. She was working the squeeze one day, handling bison. On the side of the squeeze (the metal contraption that you confine them in), has drop-down panels that open, so you can access various parts of the animal. She had been working on that when we brought in a big bison bull – so big that he pressured the sides of the squeeze so much that one of these panels opened and whacked her right on the eye. A big gush of blood came pouring out so I took her off to the hospital in Lamont.

I was sitting in the waiting room when this nurse came storming out of the treatment room and said to me, “What the hell were you doing beating this woman?” Angela had told the nurse this just to get my goat. They stitched her up and we hauled her back to work and she went right back at it. She had a beautiful black eye. She’d be a good one to call for some stories.

1835: My wife reminded me (about an incident) that we got a call one day that there was a calf moose stuck between two fences on the south side of the park, so we went down and sure enough here’s this calf. There was a place where these two fences came together, one was an intact fence that went for miles, and other was about an eight-foot fence that butted into it to help support the main fence. This calf was wedged in the corner where they met. So, I went in there with mother moose on one side of the shorter fence and I’m on the other trying to rescue her calf for her. She has her ears pinned, slashing and kicking at me and snot flying all over the place. I kept trying to get between the calf and the corner of the fence to haze it out of there and it wouldn’t move out. It continually pressed its head into the corner. At this point, my helpful wife says, “Here, use my belt.” I looped it around the calf’s head like you would a horse halter and turned it and led it out. I let the belt slide off and away they went. That was probably one of my most dangerous wildlife encounters. Most moose defending their calves can be pretty nasty.

MH: How did the Warden Service change over the years? 2000:

WO: You’ve probably heard this from everybody. I joined the Warden Service shortly after centralization took place and Wardens were moving from the backcountry into town. I remember about the second day of work, sitting at the coffee room table in Banff and listening to the old-timers, lamenting these changes and how they hated the Warden Service. Telling me that I had joined at the absolutely worst time in the history of the warden service – that it was just a miserable job now. Jaded old guys.

It’s changed a lot obviously from the district days through the transition to the current Warden Service. I much preferred the older system.

MH: What about the Warden Service was important to you? 2100:

WO: The usual list of why people liked their job as a Park Warden, you probably have enough examples. I remember once in Waterton Lakes National Park, at Cameron Lake there was a grizzly patrolling the beach near the trailhead. Earl Wilson and I went up there to put up the closure sign and to barricade the trail. We had 6-inch spikes that we were pounding into the sign at the edge of the parking area with the back side of the axe. I was holding the sign while Earl was beating away at it. We got the sign up and turned around and there’s a family from Britain, mom and dad, a girl about 16 and a couple of younger kids. I looked at the 16-year-old girl and I was stunned by the expression on her face. It was a look of complete awe. I had never actually seen anyone stand with their mouth open like that. And we were the recipients of that. Coming from downtown London to the wilderness of Waterton and see two Wardens hanging up a bear closure sign. The expression was priceless. Encounters like that really enriched the job. When you had a really positive experience with visitors from a foreign country, that was really rewarding.

MH: Are there any legends or stories associated with the Warden Service that you can share? 2250:

WO: My wife and I talked about this trying to figure out some examples. I was torn between the definition of “legend”. Is it the story of the classical legend of something like the Ghost of Windy Cabin or is it a person? There’s a ghost at Windy and another at Indianhead who lives in the basement there. It’s been a long time since I heard the story, but the one at Indianhead cabin, it’s a ghost of an old Park Warden, long dead, who lived in the basement, I think he was a short little guy who would come upstairs and do some weird things at night to people who were staying in the house. I remember being in that house with Keith Everts, Perry Jacobson and Rick Kunelius. We had done all our evening chores and had just gone to bed when there was a big ruckus in the basement. It sounded like somebody was beating pots and pans and doing weird things in the basement. All of us got up and went stumbling down the stairs to see who the hell was in the house with us, and of course, there was nothing. In hindsight, we suspected that it was the old furnace creaking and groaning. It sure sounded strange. I’m pretty sure it was at Windy that Frank Burstrom refused to sleep in the house. He would sleep in the woodshed instead because of the ghost. Frank’s one of my favourite wardens. If there is a legend in the Warden Service, it’s Frank. More experienced man than many of the other wardens.

Are there any publications about the beaver in Elk Island that I could use as a fact base for a fictitious children’s book? I am trying to gather information on what animals typically share the habitat with the North American Beaver and how they might interact with the beavers. A sound fact base on beavers is imperative and I am having a hard time finding a great resource.