Thank you to the Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies for granting permission to the Park Warden Service Alumni to post this interview on our website.

This Oral History interview was funded in part by a research grant received in 2019 from the Government of Alberta through the Alberta Historical Resources Foundation.

Park Warden Alumni Society of Alberta

Oral History Phase 9, 2019

Interview with Frank Burstrom

Date/time: November 30th, 2019@1000 Exshaw

Interviewed by Monique Hunkeler

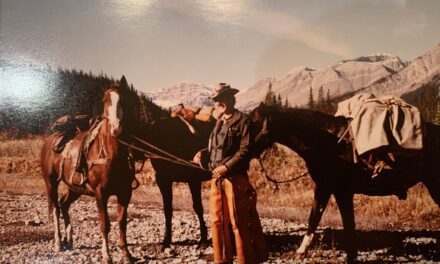

Frank Burstrom

Place and date of birth? Jasper, Alberta on May 31, 1956

MH: Where did you grow up?

FB: Grew up in Jasper

MH: How did you become involved in the Warden Service? Which national park did you start working in?

FB: Basically it was kind of a family business. My Dad (Alfie) was a Warden and my Grandfather (Frank) before him and it was what we knew how to do, what we liked to do. My first job was in Jasper National Park, start date, July 11th, 1975.

MH: What made you want to join the Warden Service? 0100:

FB: It’s all I knew how to do properly. Mostly I liked my backcountry and it was a job that paid me to saddle up and leave and to me, that was the ideal thing. I wouldn’t have traded any other job for it. And also, the people that you worked in the Warden Service with were kinda like family in a lot of ways at that time. A great place to grow up as well as work.

MH: What different parks did you work in? How did they compare? Do you have a favourite? 1135:

JB: Jasper as a patrolman for 3-4 years and went to college at the same time. From there I went to Pacific Rim National Park, 1979-1981. I’d never seen the ocean before. Spent a couple of years there (where I) worked with Scott Ward, Gordon McLean, few of those guys. Worked in Lake Louise for a couple of years, then out of Rev/Glacier, Banff, Grasslands and then back to Banff. Every Park was unique and different. There are no ugly National Parks, haven’t found one yet. The environment at Pacific Rim was probably the most challenging because in the 1970s, they used the Expropriation Act to create the Park and so we weren’t very well liked in the local community. It was basically a war zone between the locals (fisherman and loggers) and us. There you had to be a little bit careful. You wouldn’t go into the bar by yourself because sometimes there was a big battle. After working there for a couple of years, I transferred around to a couple of parks, the last one being Grasslands which was a relatively new park at the time, and before I went there, that was one of the first questions I asked, “Did you use the Expropriation Act and are you planning to?” and they said, “No”. Willing seller, willing buyer. That made it easier to go there because I didn’t want to go into another war zone, that just didn’t make sense. In Rev/Glacier, I was on special projects out there, twinning of the CP Rail. I was environmental Protection Officer at Rogers Pass for 2 years, then back to Banff. And from Banff to Grasslands for 2.5 years. Every Park had something unique and different about it so I don’t really have a favourite. I’d say Grasslands was one of the places I almost didn’t come back from. It wasn’t so much to do with the park although it was very interesting, it was more to do with the people. The neighbours in Southern Saskatchewan are some of the nicest people in the world.

MH: What were some of your main responsibilities over the years? 0605:

FB: It varied. Grasslands, Fire was one of my main responsibilities there. Prescribed Burn Program as well as wildfires. In Banff, most of it was backcountry, looking after various districts, everything from Bryant Creek to Indianhead, so all over. In Pacific Rim, I was more of a generalist, working the long beach section, dealing with illegal campers, water rescue, basically the full gamut there, some law enforcement. And in the winter months when I got laid off the Warden Service, I hired on their trail crew, West Coast trail building bridges and trails. Rogers Pass that was Environmental Protection Officer during the tunneling project, looking after environmental issues that had to do with clearing of the new right of way and basically managing environmental protection with 2000 man camps so a lot of people. It was about 1983ish.

MH: What did you like / Dislike about being a warden? 0810:

FB: Saddle up and leaving. One of the funny ones, basically my first wife didn’t understand that, why I was always leaving. One of the funniest radio calls I got when we used to do the call-ins. I got to Mystic and I had a message from Dispatch. The message was from Terry, “your supper is getting cold”. Oh, I had forgotten to tell her I was heading into the backcountry again. But she had 10 days to get over it.

0910: Basically, some of the tragedies that could have been avoided. I remember doing one search in Lake Louise where a little fellow about 3 years old, had gone through the ice. Little McAllister boy. And we didn’t get him out in time. We all have a mixture of tragedies that we’d just as soon not remember. Worked on lots of traffic accidents, Rogers Pass. One winter there were 9 fatal accidents within 5 days at Christmas time. It was a slaughterhouse. So, a bunch of tragedies. That was the part I didn’t like about the Warden Service job.

MH: What were some of your more memorable events as a Warden? 1025:

FB: Nothing that really jumps out at the moment, it all blends together. There were a lot of highs, and a few lows like I just mentioned, some of the traffic accidents and other tragedies that you dealt with. Avalanches and stuff that you worked on. Nothing that really jumps out at the moment.

MH: Can you tell me about any rescue/wildlife stories that stick out in your memory? 1100:

FB: Working on Avalanches, that one up on Healy Creek where a few people were killed. It was tragic. I had skied out from the (Egypt Lake) Cabin and come out to the parking lot and when I got to the parking lot, some people came up to me and said, ‘Have you seen our friends?” and I said, “No, I haven’t seen them”, “Well they are supposed to be coming down the trail.” And I thought about it for a minute and I realized there was an avalanche that I had skied overtop of and there were no tracks on it, so I knew where they were so I initiated the call to get search and rescue in, but by that time, it was a moot point. We were on that slide for quite a number of days. It had been balmy warm, chinook conditions when the slide come down and then it got really cold, that massive temperature change. The people had done everything right, but God said no.

1303: I worked on a series of bear mauling’s over the years. All the ones that I worked on, the people survived, some of them fairly badly injured but they survived. And it really made me a believer in bear spray. I saw where it works. The one we did on Allenby Pass, that bear mauling there, two people were hiking up the pass and got a ways away from each other and the sow with a couple of cubs met the one fellow in the lead and went after the guy. The guy had gotten his bear spray out but the bear had gotten him down. The other guy came running up the trail and distracted the bear momentarily and then the bear started to go after him as well and they literally stood there as the bear circled around, spraying pepper spray and after the incident, the cubs caught up and went by and ran down the other way so the sow followed the cubs and left the two guys alone. The one guy hiked over Allenby Pass to Halfway Cabin and got a message out that his friend was badly injured up there so we flew out to help him. They were so covered in pepper spray, that when we put them in the helicopter, all our eyes were watering. I was wondering if the pilot was going to be able to see! So that was definitely an incident where pepper spray paid off. It definitely works.

1500: Another one over towards Bourgeau, the guy was taken down three times and survived every time. The bear went after him in the alpine, took him down. The guy played dead, the bear went away, so the guy got up to run and the bear saw him get up, went back after him and took him down again. He played dead, the bear left him alone after biting him a couple of times and rolling him around. And then he got up to run again, he was closer to the trees, he thought he could make it to the trees but he didn’t. Bear took him down again. This time he stayed down, playing dead for much much longer, because he was badly injured by this point. Bear left him alone, and he was probably on the ground for close to an hour, playing dead, and another hiker came along, found him and ran out and reported it. But the guy survived, three attacks from the same bear. It was interesting.

MH: How did the Warden Service change over the years? 1650:

FB: Certainly Public Safety definitely changed quite dramatically in the 1970s. We had to become much more professional in what we did. A little higher level of training became more of a priority. There were a lot more rescues, a lot more people in the park doing high end climbing (North Faces) so that meant we had to increase our response level. And really, guys like Peter Fuhrmann played a major role in that, developing helicopter rescues and that sort of thing.

The other changes in the Warden Service, of course the last one was the Law Enforcement thing, that still kind of pisses me off. In my mind, Law Enforcement is not an entity in itself, it was really a tool in your bag to do your job, but it’s just a tool, there are other ways to do your job as well. And you brought that tool out when you needed to (campgrounds, boundary patrol etc.) and if you didn’t need to, that’s okay. It was unfortunate to see the break up that happened in the Warden Service and really you don’t have the same group of people anymore, they are more separated. That’s a shame. To have Law Enforcement as just the job, it’s mind boggling to me. They must get pretty bored. That was a break up and I wished that hadn’t have happened.

I remember working on the Brazeau Bandit case in Jasper and we never really thought about whether we should be armed or not. We always had a rifle. The Brazeau Bandit was a Metis fellow out of the states. After 30+ years, they finally found the end of the story. We did a native (backcountry) ride. Dennis Herman had set up a ride with the natives and the outfitter, Charlie Abraham. I remember chatting with him at Indianhead about the Brazeau Bandit incident. I asked him if he remembered anything about that and he said, “Yes my wife was at Small Boy’s Camp.

(Chief Johnny Bob Smallboy (7 November 1898 – 8 July 1984), also Robert or Apitchitchiw, was a community leader who brought national attention to problems faced by urban and reserve Indians of when he “returned to the land” with followers from troubled Canadian Indian reservations. He was born on the Peigan Nation, SW of Fort Macleod, Alta on 7 November 1898, of a traditional Cree family who were among the last to settle on their allotted reserve at Hobbema in central Alberta. A Treaty 6 nation location between Calgary and Edmonton and located on oil and gas reserves.[1] Smallboy became a hunter, trapper, farmer, and eventually chief of the Ermineskin Band from 1959 to 1969. In 1968, to escape deteriorating social and political conditions on the reserve, he moved to a bush camp on the Kootenay Plains. He attributed the alcoholism, drug abuse and suicide that he saw in his community to living modern lives on the reserve. Accompanied by approximately 125 people and with help from other elders he moved his community. Despite factional splits, the return of many residents to Hobbema, and the group’s failure to obtain permanent land tenure, Smallboy Camp persisted into the 1980s as a working community used as a retreat by Plains and Woodlands Indians from western Canada and the US.[2] Smallboy received the Order of Canada in 1979.)

(which was the camp that Dad (Alfie) and I had ridden into after tracking the fellow over there, but we didn’t get much response from the people there because we were in uniform and searching for this guy) and you guys were standing beside him”. We were at Small Boy’s Camp when we finished our search and the Brazeau Bandit was there, but nobody pointed him out to us. The Brazeau Bandit basically got tired of walking and had an opportunity and held up a Backcountry Warden at gunpoint, stole his horses, packs, boots and locked Dave up in the tack shed and rode off into the sunset. The initial response from Jasper end was to put some guys in a helicopter, fly over, pick this guy up; arrest him. And once they spent a while searching, they didn’t find him. And the reason being, you can hear a helicopter coming from a long way away, and you duck under a few spruce trees and they fly by. So my Dad was working on that one and I was over on the Lower Smokey when that happened and I got a message that they were going to fly me out because dad had made a request that I go with him to do the ground search. This is now a week or so after the incident. So they flew me out, I met up with Dad, got a truck, cruised down on the Blackstone, and we were able to find our Government horses (Dock and Dexter), they were running with the wild ones up there. So we got them back and we started figuring out where this guy had come out, and we found where he had picketed his horses, laid around camp for a day or two. He wasn’t in a big rush to leave the country. We got some of the packs back – up from Small Boy’s Camp, so we knew he’d gone out through there. But our response from Small Boy’s Camp, because it was a part of the American Indian Movement (it was a bit of a radical band that set up over there) and they weren’t interested in talking to us and giving us any information, so the case kinda went cold after that. We did get our horses back, and we ended up with an extra one out of it. The mare got pregnant. But I remember chasing the wild horses and trying to get our horses back. I saddled up and went after this wild bunch, ducking through the timber and it was probably some of the wildest riding I’ve ever done. It was getting dark, time wasn’t on our side and Dad decided to stay with the truck. Eventually our government horses weren’t as interested in running as fast or as hard as the Wildies, so I was able to catch them. They were used to being looked after so the freedom of the Wildies wasn’t for them. Yes, so it was pretty wild, finding out that we were basically standing beside the Brazeau Bandit at Small Boy’s Camp. In the end, we assumed he was killed in the States. He’d escaped custody a couple of times and they shot him down there. It was about the same sort of timing that the Claude Dallas event was happening in the States so we weren’t sure if we were dealing with him. Fortunately we weren’t.

Always fascinating reading about these amazing guys and their history in the Parks!

Thanks for sharing!

Dan