Thank you to the Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies for granting permission to the Park Warden Service Alumni to post this interview on our website.

Park Warden Alumni Society of Alberta

Oral History Phase 10, 2020

Phone Interview with Paul Galbraith

Date/time: May 11, 2020 1030

Interviewed by Monique Hunkeler

Place and date of birth? Born in Invermere, BC, 1948

MH: Where did you grow up?

PG: Grew up in the Columbia Valley, graduated high school in 1967, left the valley to attend school; worked with BC Forest Service in the summers.

Attended:

Caledonia College, Agricultural Campus in Dawson Creek 1969/70

Lethbridge Junior College – Conservation Law Program 1971-72

University of Saskatchewan – Ecology/Geography

University of Waterloo – Honors program in Environmental Studies.

MH: How did you become involved in the Warden Service? Which national park did you start working in?

PG: As a student I worked with the British Columbia Forest Services in Fire Suppression, 1969 I worked on the Big Horn Sheep Research study in Kootenay National Park and did some range analysis for the East Kootenays alongside Parks Canada employees. The next summer I worked as a Park Warden. Kootenay National Park was my first park 1970-1972 as a seasonal Park Warden, working with Ian Jack, Larry Halverson, and all those other bad actors. Max Winkler had just left when I got there; John Turnbull and a few other good old-time wardens were there. It was a good time as a Seasonal Warden.

MH: What made you want to join the Warden Service? 2220:

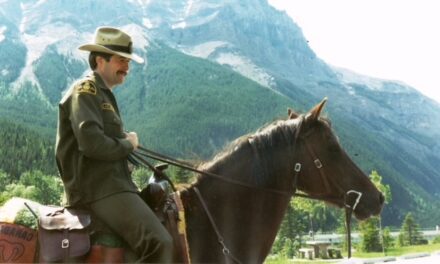

PG: The people that worked there. When I started working with the Big Horn Sheep group, Naturalists and Wardens that were there. I grew up on horses and in the Warden Service you could go for a ride on your horse once in a while, it seemed to be a good idea. I never did well in geography in high school, so I decided to take some geography lessons across the country. My wife is bilingual so I thought it would be good to go to places where she could speak her language (French), like New Brunswick. It seemed like the right thing to do at the time.

MH: What different parks did you work in? How did they compare? Do you have a favourite? 1135:

PG: Kootenay National Park, Seasonal Warden 1970-1972

Prince Albert National Park, District Warden 1973-1976. I was the Kingsmere District Warden working under the District System for one year and then the Chief Park Warden brought me into town. He wanted someone to head up the Law Enforcement Program and so I did that for 2-3 years. They had some serious Law Enforcement in that Park. It was in Prince Albert National Park that I first worked with Duane West. Duane had a deep appreciation for conservation and First Nations. He was an inspiration to us all.

Wood Buffalo National Park, Resource Manager of the Peace Athabasca Delta (1976-1980). I was there during the Bison anthrax outbreak. It was a very nice time to be there, good staff, good local aboriginal employees. I learned to speak a little Cree, enough to get by in the field and I had a dog team.

Fundy National Park, Chief Park Warden 1980-1982. It is a nice little park. There was a lot of work to be done so it was an exciting place, and we were able to get money to put into the park. During this time Canada had its Green Plan going so we funded the reintroduction of Peregrine falcons to the Eastern seaboard. The program was centered in Fundy National Park with Anne Morceau looking after the interpretation and she was fabulous. We used Wood Buffalo peregrines for the introduction in Fundy. I believe there are 32-34 confirmed nesting pairs in that region.

Terra Nova National Park, Chief Park Warden 1982 – 3-4 months to clean up a situation. I was on my way to Gros Morne, but they wanted me to go to Terra Nova to get people working on the Conservation Plan.

Gros Morne National Park, Chief Park Warden 1982-1985. It was just being established. A beautiful Park, and the staff were excellent, many later transferring all over Canada to work. Jeff Anderson, Chip Bird, Peter Deering, Daniel LeSauteur, Roger Baird, Barb Heinleman, Dan Reeve, Norman Wentzell, John Taylor, Dan Couchie –a great bunch of staff; very dedicated to establishing that Park. It was tough because people there (in Gros Morne National Park) were used to doing everything, like shooting moose. One year we had 19 moose and caribou poaching cases in the Park: more than the total poaching cases in all the National Park Service across Canada. After an interview in Deer Lake about poaching cases, I was walking away and said to one of the Wardens (and you should never do this after a news conference, when you think everything is off the record) I said, “You know Newfoundlanders, they have to eat too”. As the reporter was talking disparagingly about the families we were picking up as poachers. Of course, news media with their parabolic mics picked this up and it was the local news story…the Chief Warden says Newfoundlanders have to eat too. Did not go over too well with the Superintendent of course.

Prince Albert National Park, Chief Park Warden 1985-1992. Worked with a bunch of great staff there. Got a few things done, Fire Management Program, Aquatics Program. Prince Albert is a nice park.

From 1991-1992 I worked out of Regional Office in Winnipeg as a Manager for Strategic Planning for the North, the Prairie Parks and the Yukon while still living in Prince Albert National Park. Working on strategic issues in those Parks.

Jasper National Park, Chief Park Warden 1992-1998. Jasper was a great place to work. The interesting thing about Jasper was that there were so many staff that had been there so long that everyone knew their job perfectly. They had a lot of experience however not much Regional interaction. One of the things done as the Chief Park Warden is to look at what’s going on within the whole natural region around the park, see what the issues were there, and then do things in National Parks that make a difference in the natural region. One natural region for Jasper was the mountain region, all the way from the TransCanada Highway up to Swan Lake, all the natural region on the foothills side. That is a big region. On the British Columbia side, there is the whole Mount Robson region, which is quite different. The programs had to be expanded, which the staff were receptive to. We started to get involved in other programs like the Model Forest and the Inter-Mountain Region projects and it worked out. You can still see the programs that originated in Jasper during that time. The Jasper wardens had a program to prevent wildlife from being run over on the Yellowhead Highway that worked and we said, “Let’s make this program Regional, to go from the other side of Hinton all the way to the other side of Mount Robson. Work with people there and see if we can get the program on a much larger scale. Truckers going through would know there were certain areas they needed to slow down due to wildlife.” It was done and was very successful. When you drive from Jasper to Prince Rupert, you see the same types of programs as in Jasper, slowing down the traffic on the Yellowhead Highway. National Parks can do a lot of work that influences the entire Region, making the Park program relevant on the broader Region.

1645: Look at the traditional territories of Aboriginal people and tie that into the Parks’ program. The First Nations that have thought this through can see some things we do in National Parks that are good for their regions as well and we were able to write in some language that they are using now. When we did the Model Forest in Jasper and the review for the Cheviot Mine, we were able to sit down with First Nations and write what they thought was important in their territory and, with the help of Mike Gibeau, Cliff White, Wes Bradford, George Mercer, Shawn Cardiff, Janet Mercer and some US researchers, put that information into biological terms. We were able to look at what they wanted to see on the landscape, put it into biological terms and then put numbers by it so they (First Nations) could see how meaningful it was. They could see what had happened in other areas where it was improperly outlined and the landscapes got totally crisscrossed, ruining the landscape with ATV’s, etc. It was a way of working on First Nations concerns and issues. The role of the Chief Park Warden was to make the program in the Park relevant to the region. The problem with that was, (and this was part of the demise of the Warden Service), although the Chief Park Wardens, the Chief Naturalists and some Superintendents were doing that (Superintendents like Dave Dalman who knew all about that and wrote the book on serving the larger natural region), many Senior Managers had no idea what we were doing. They did not understand what we were doing; and that contributed to the demise of the Warden Service. When we worked with the bear garbage issues in Banff, all those bear containers were designed and developed by Wardens. I was in New Mexico last year and the very same patented bear proof garbage containers are all over the continent, designed by Wardens in Waterton and Banff National Parks. The new Senior Managers did not get this and really had no idea what we were doing. They (Senior Management) would come into the local Park office and see maps of our local region, the traditional territory and the surrounding area, and they would say, ’You should have maps of all the National Parks in Canada.” In Prince Albert National Park, for example, most of the people coming to the Park will never see another National Park, but they will live in this Region for the rest of their lives. The Regional maps are still out there in some National Parks, these old signs of poor maps showing some park down in Cape Breton Island…someone in Banff cares about that? That was one of the divides that happened in the Parks Service.

21:50 PG: I do not have a favorite Park. Every Park we lived in was my favorite Park at the time. As the Chief Park Warden, you have to be the cheerleader for your Park and the Park Wardens that work there. The only comparison I can make is that smaller Parks tend to have a stronger focus on regional integration. Larger Parks tend to be more independent from the natural region or the traditional aboriginal territory.

MH: What were some of your main responsibilities over the years? 1155:

PG: Public Education; Law Enforcement; Resource Management; Strategic Planning; Regional integration; recruiting quality staff; attracting top level researchers to work in Parks in a multi-disciplinary setting; staff training and development.

More as a Chief Park Warden than as a Warden, one of my main goals was to attract top level researchers to work in parks. In several parks (Gros Morne, Prince Albert, and Jasper), we set up multi-disciplinary teams of researchers to work on natural region issues. I am a believer of science, the role of science and that science should inform decision making, so I spent a fair bit of effort to do that. I spent a fair bit of time in Law Enforcement and Resource Management Planning, Fire Plans and Strategic Plans on a regional scale. Recruiting quality staff to me, was a major issue. Bill Dolan was responsible for hiring many of the excellent staff hired over a 20-year period. I was a generalist type of guy. We wouldn’t wonder if this was a job that would fit with what the wardens were supposed to do. If something came down the pipe our way, we would just say, “let’s do it”. We did not try to fit it into some category. We had a huge program in Prince Albert National Park which ended up involving 50 NASA scientists doing research on carbon exchange between the boreal forest and the atmosphere. We didn’t know it was going to get that big, but it did. Received a good snapshot in 1990 that this was the situation with carbon exchange between the boreal forest and the atmosphere.

MH: What did you like / Dislike about being a warden? 2700:

PG: I always felt that what the Warden Service did was very valuable, not only in terms of people having a place to enjoy the natural environment, but on a national scale. I felt it was possible for National Parks to play an ever-increasing role on environmental sustainability. The Warden Service – some people say they had an emotional attachment to the Warden Service, I did not feel that. I felt it was a very convenient way to get a very important job done. The icon image of the Warden Service was that they were very good instruments out in the field to make a real difference and to make the parks program relevant on a regional scale. I never heard anybody say the Wardens did not know what they were talking about on environmental issues, for example bears. I had more of a sense of responsibility towards environmental issues on a regional scale than the actual operation of the Warden Service. That may be different from what some people had which was more of a kinship to the Warden Service. George Mercer has statements in his books that showed he had a much more attached view of the Warden Service than I did.

Dislike: Cannot think of anything other than I think that we should have been paid more. I should tell you this story about the Warden Service. At one time we had a regional office and a headquarters office. There were many people who weren’t really involved directly in the parks program. Being a warden out in the field to me was an enjoyable job. One time there was an important fellow, Francois, coming out from Ottawa and he decided to come up to Jasper for a few days. Brian Wallace and I took him out to the Amethyst Valley on horseback. We left at 0600 in the morning after we got Francois adjusted to the horse and headed up the valley. At 1000, Brian and I got off our horses, walked to the riverbank and hung our heads for a few minutes; put our hats back on and got back on the horses. We never said anything. It was obvious that we were paying our respects to something. We arrived at the cabin and Francois said, “What was that little thing you did at 1000 back there on the trail?” Brian said, “We actually do that every morning. We say a small prayer for you poor buggers in Head Office, but we really appreciate what you do for us.” He went back and told the guys in Ottawa, which I heard about.

MH: What were some of your more memorable events as a Warden? 3248:

PG: It has to be the people across the country. I think making the Parks Canada program relevant across the country to me was a memorable event. Signing things into law like the Model Forest programs or Regional programs that Parks were very much a part of. I think we had an excellent training program, training generalist Wardens at the National Training Centre. We hired the best staff in the country. People would come out of university or technical college and the first place they wanted to work was the National Parks. Talented staff able to get things done, working in Parks across the country. Meeting and working with Park Wardens, other dedicated Park staff and Resource staff within the Region around the parks I found out early in my career that working in a cooperative, collaborative manner with Provincial and other National agencies could make the Parks Canada program successful and certainly more relevant.

MH: Can you tell me about any rescue/wildlife stories that stick out in your memory? 3440:

PG: One of the characteristics of the Warden Service is that if one slipped up you had to live with it for a long time. I had a problem with “aircraft crashes”. It started in 1973 when we put a Cessna 185 through the ice while conducting a Caribou survey near the Northwest Territory/Saskatchewan border. No one was injured and we got to shore, found an old trappers’ cabin for a few nights until our three fires were spotted by the Hercules (Search & Rescue)

The next incident occurred in 1975 when we landed a Cessna 172 in the trees west of Prince Albert. A few bumps and bruises but everyone was fine. The next day we rounded up another aircraft and continued the survey. As we pulled up to the terminal in Prince Albert Ray Whaley quipped, “That was the best landing we’ve had in two days”. About five days after we moved to Wood Buffalo National Park some wardens were working a fire just north of the Birch Mountains when a Medium working a bucket flipped upside down in the lake. The Chief Warden called me that night for a briefing and kind of hinted that perhaps I brought the aircraft jinx to Wood Buffalo.

In July 1987 we were working a fire in Prince Albert National Park with an older Sikorsky 55; it was transporting crew and bucketing. Greg Keesey was the Fire Boss with a crew of eight at the fire. Jean Fau, Sherri Baird and I were in the Fire Control Centre; Greg was talking on the radio at the time and you could hear the machine working nearby. All of a sudden Greg’s voice pitched, “Holy Jesus she’s down”, “Oh my God…”. and we could hear the breaking sounds of the machine crashing into the trees. About twenty seconds went by and Greg said, “The pilot is OK, nobody hurt”, and then complete silence for like two minutes. Jean Fau calls, “755 from Base; 755 from Base”. Another long two minutes go by nothing! Suddenly Greg comes on in a calm, collected voice, “Base from 755, we are going to need another machine out here.”

In the 90’s I was catching a flight out of Edmonton going to Fort Smith and another Parks Canada employee was catching the same flight. As we got talking, he asked, “Aren’t you the aircraft jinx guy?” “Yeah, I guess”, I said. We boarded the plane, a 737, and were about four minutes into the flight when the Captain came on the intercom, “Some problems with the main door and cabin pressure, we will have to return to the airport.” Just then a chunk of black plastic flew by the window. We headed back to Edmonton where we were greeted by fire trucks, etc. They ordered up a new plane and we were all set to go when I noticed that Gord was over at the ticket counter switching his ticket for a later flight. Some things you just cannot live down.

3518 I was always impressed with the staff.

MH: How did the Warden Service change over the years? 3712:

PG: When I joined the Warden Service in the 1970s, there was a large military influence and many of the Wardens, Superintendents, Maintenance staff and Visitor Service staff were veterans. Most were disciplined and used to following orders. Apparently, there was an “order” (policy) that Wardens should shoot wolves, cougars, coyotes, and osprey on sight. The new Wardens coming into the service with a biological background understood the critical role that predators play in the ecosystem and, of course, did not agree with the “policy”. We didn’t want to challenge the Park Managers, so we held a little meeting at Kootenay Crossing and made a pledge to just ignore the “policy”. A couple of years later the Chief called us to a meeting in Radium to discuss killing of predators. We all thought that the Chief had found out about our meeting where we decided to ignore the official policy. The Chief kind of nervously brought out a memo and started reading. The memo was quite long and talked about the role of predators; near the end of the memo the Chief kind of choked up and then in an authoritative voice said, “I am ordering you to stop killing predators. I don’t like it but that is the order.” John Turnbull, the Warden from Marble Canyon said, “Well Neil, that’s easy, you (the CPW) are the only one who shoots predators. The Wardens stopped killing predator’s years ago.”

MH: What about the Warden Service was important to you? 4145:

PG: I always looked at the Warden Service to get things done. I was always thinking about what the wardens could do at the Park that would assist the natural region. We had at that time, a kind of dual mandate. We had park visitors versus the environment and the wardens were out there trying to protect everything and the other staff were trying to get visitors out there. I never viewed parks in that way and a lot of people in my era felt the same. We didn’t buy into the dual mandate. We said the role of parks is to promote an understanding and respect for natural ecosystems so of course people should be coming. We should value visitors and the quality of the experience in terms of how well it promotes an understanding of ecological processes and cultural heritage.

Places like Banff, the thinking was you could just jam everybody into downtown Banff, and it doesn’t matter what they do as long as you don’t affect the ecological integrity outside that little circle. To most of the wardens I knew that did not make any sense. People should come to National Parks for a National Park experience and to understand nature. They should not go there to golf and ski. Those things that are peripherally associated with understanding ecosystems, as far as we were concerned, have no place in National Parks. When Lower Fort Gary was established as a National Historic Site, it had a golf course. Within a week, we closed the golf course. It was not appropriate for a National Historic Site. I think the same about golf courses and a lot of my warden friends felt the same way about golf courses and for the most part, ski hills; although there is some value in having Sunshine Ski Hill as a historic area. We were expanding the ski hills and going in the opposite direction and we did not agree with that. People should be thinking of National Parks as a place to come and understand nature, not a place to come and party. The trap you get into is the only way you can do this is to fight on the ecological integrity scale and to start fencing everything like Banff highway. You do these things, and the park keeps growing and there are more skiers every year. The park-centered response was fencing and how does that enhance people’s understanding of nature. What happens from the park-centered view in my opinion, is you start embracing programs like the Yellowstone to Yukon which to me is a very park centered view but in the long term, I don’t think It will be successful. You must apply those ecological principles on a much larger scale. Ecological integrity examples should be shown throughout the natural region, so those programs are counter-productive to long term thinking about our survival as a human race in this country. I do not support and never have supported the Y2Y initiative.

4800 Paul’s notes: I never bought into the dual mandate of National Parks. The idea of preserving/protecting while optimizing use; a set-aside (preserves) romantic view of the world. The Park-centered view separates National Parks from their natural region and from traditional territories, the viability of Regional Ecosystems. The Park-centered view has also led to initiatives such as buffer zones, Yellowstone to Yukon. More importantly, the park-centered view constantly pits ecological integrity against human activities. The Mission of National Parks is “to promote an understanding, appreciation and respect for natural “regional ecosystems”. We can do this by:

maintaining ecological integrity

provide meaningful and quality visitor learning experience

research

communication, etc.

Hi Paul thanks for hiring for full time position in Wood Buffalo at Fort Chipewyan. Thanks for allowing me to take on some of the projects that where ongoing when I came in. It was good to here about you and your career.