Thank you to the Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies for granting permission to the Park Warden Service Alumni to post this interview on our website.

This Oral History interview was funded in part by a research grant received in 2019 from the Government of Alberta through the Alberta Historical Resources Foundation.

Park Warden Alumni Society of Alberta

Oral History Phase 9, 2019.

Phone Interview with Sylvia Forest

Date/time: November 27, 2019 @ 1300

Interviewed by Monique Hunkeler

Place and date of birth? April 1st 1960, Edmonton, Alberta

MH: Where did you grow up? Calgary, Alberta

MH: How did you become involved in the Warden Service? Which national park did you start working in?

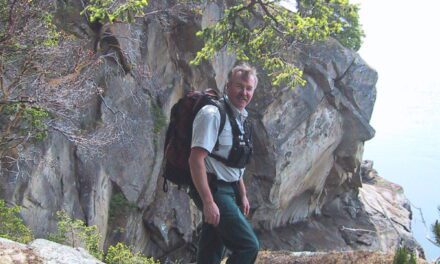

SF: That’s an interesting story. Basically, my sister Kathy Calvert, as you probably know, was one of the first female Park Wardens hired in Canada as part of a diversity initiative. I like to think of her as the first, although there were three hired all at once, she was the only one that lasted. I had a lot of influence from Kathy, watching her in her role as a female Warden, and I got to see what the job was all about. At the same time, I was struggling through University and realized that academia wasn’t my strong point so although I managed to get my degree, I knew that getting work in a field that was more active and outdoor related would really suit me a lot better. I had various jobs that led me in the direction of the Warden Service; as a climbing gym instructor at university, I grew up climbing with my dad, so I had a strong mountaineering background, and loved horses, and all of those things were things you got to do when you joined the Warden Service so I applied a couple of times. The first time I didn’t get short or long listed, it was very competitive, but eventually I managed to get an interview and got a job. I started working in Jasper National Park. I moved there to work at Marmot Basin Ski Area as a ski patroller and that gave me quite a bit more experience in Avalanche Control and other great things, and then as a result, I got introduced to the idea of working on trail crew, and got on with the fly in trail crew in Jasper and then after that, it opened a few doors to get me into the Warden Service.

MH: What made you want to join the Warden Service? 0340:

SF: Seeing what a cool job it was, seeing what my sister Kathy got to do for work, and she did a number of backcountry patrols back then and in that day, friends and family were allowed to tag along so I did a lot of trips with her and thought, “This is a great way to make a living, running around on horseback”. She was involved in a lot of other things, Public Safety, which was right up my alley, climbing and mountaineering, the idea of doing rescues, I was completely enamoured by pretty much everything that Park Wardens did at that time. There was nothing I didn’t like, it was right up my alley.

MH: What different parks did you work in? How did they compare? Do you have a favourite? 0445:

SF: I started in Jasper and spent the better part of 18 years there, but in that time, I also went to Elk Island for 3 winter seasons and one summer season (1.5 years total), working with the wildlife primarily. I worked in Lake Louise for one summer season and I worked in Revelstoke/Glacier for 8 years.

0525: I would have to say that Jasper is my favourite. They were formative years for one thing and I made the closest lifelong friend in Jasper. It was my home for 18 years and it is a really special place. It’s a little wilder and freer at the time. Banff and some of the other parks were under more scrutiny, Jasper had a little more “wild” in it. For seven of those years, I was stationed at Sunwapta Warden Station on Highway 93 North and that was really special times. (It was a) special community and developed some very close friendships there. But that being said, Elk Island turned out to be an amazing highlight and I was so grateful that I was able to work in Elk Island. The experience working with wildlife and again, the very close friendships I developed while I was there was a very cool working environment. And it was something totally different, got me out of the mountains and I was very interested in wildlife. I think if I hadn’t gotten on with the Warden Service, I probably would have gotten into some sort of Wildlife Management somewhere along the way. Rev/Glacier was very interesting but very challenging, which I’ll elaborate on later.

MH: What were some of your main responsibilities over the years? 0730:

SF: When I stared in Jasper, I started working in fire history which was really interesting. We either hiked, flew or rode horses into the backcountry and investigated the fire history of Jasper in some of the more remote areas which was very interesting. I worked as all wardens did, put in my time in operations, which is a certain amount of Law Enforcement and general park operations. Part of operations was managing elk in Jasper. At the time, there were many elk in the townsite, cows having calves in the townsite, large herds in the townsite area. For 5-6 years, I was a backcountry warden and patrolled the Smokey District on the north boundary of Jasper. Again, it was 7 years at Sunwapta which was general operations with a focus on Public Safety and Avalanche Control. In Elk Island of course it was primarily wildlife management. I was put in charge of the Beaver Management Program, I assisted with the Elk Management Program and took a lead role with the Woods and Plains Bison Management Program, which was very interesting. I did a certain amount of obligatory vegetation work as well. In Rev/Glacier, I went there as the Visitor Safety Manager.

MH: What did you like / dislike about being a warden? 1005:

SF: I liked pretty much everything. Certainly in the earlier days in Jasper, and I’m sure that you’ve heard this lots from other people, in a given day you could be lighting or extinguishing a wildfire. We did a lot of prescribed burns which were becoming more of a highly used management tool and I just happened to be in a position of being a part of various ignition teams doing wildfire, or you might be dealing with wildlife in townsite/campgrounds, bear jams. On any given day you might be asked to go out on a rescue, and back then, you didn’t have to be part of the guiding community. As a generalist with training and interest, anybody and everybody could be part of a rescue operation. A certain amount of law enforcement, enforcing the act and regulations. So on a given day you could be doing almost anything regardless of whether you specialized in it or not, and certainly at Sunwapta…we used to call it Sunwapta National Park because we were somewhat autonomous. I loved every part of it. There wasn’t anything that I didn’t like, it was all very interesting.

1200: SF: Nothing (that I did not like). I loved being a warden. It was a really great job. If I had a least favourite, I wasn’t particularly driven in terms of Law Enforcement. Early in my career, we all had to do a certain amount of that. General Operations wasn’t my favourite, I preferred doing other things, but on the same hand, it allowed you to dabble in everything so it was pretty interesting.

MH: What were some of your more memorable events as a Warden? 1250:

SF: I looked at that question and thought, “How do you answer that because, how many hours do you have?” I think I’ve highlighted it but I think that every aspect of the Warden Service that I participated in, which was pretty much all of them, had something memorable. For example, in Law Enforcement, I ended up being a part of a poaching investigation where I was a key witness. That was really interesting and I learned a lot about the whole process and testifying in court. Moving onto wildlife, in Jasper, when you had a cow elk have a calf, it often happened in somebody’s back yard, a school yard or the campground or in a place where there was a lot of public and the cows would get very aggressive. The management tool at the time, and I think they might still do this, was to get a small team, one person of good stature that would pretty much grab the calf and relocate it to a more appropriate and safer location for the cow and calf, and the other part of the team would have shaker sticks, like hockey sticks with streamers, to distract the cow, and the cow, obviously wanted to stay close to the calf, so sometimes it became very exciting. A fairly drastic management tool but it was effective and became safer for the public and the calf and cow.

But sometimes things didn’t go as planned. (I’ve) definitely been involved in some pretty interesting rescues over the years. That was my key role, especially closer to retirement and several fatalities over the years that you had to manage and then lots of success stories too where you were made to feel like your intervention saved a life and that was pretty amazing. How many people can say that…pretty amazing. 1600: Getting back to the wildlife, working in Elk Island, it’s a small park surrounded by farmland and the interface between the park and the rural community is a fence so as a result, you have a lot of issues that come from that. There is no natural predation so your ungulate population can explode if it’s not controlled, which leads to other problems, loss of habitat so on and so forth. Same with the beaver populations. It was a Park with a lot of intervention. A lot of what we did were wildlife counts to determine carrying capacity of the landscape and creating a culling program to remove some of the wildlife from the landscape by luring them into traps, keeping them in pens until you had a full number and then export them for either repopulation in other National Parks or Wildlife Refuges, and so forth. So I was quite active in that. It was all done on foot and a lot of the herding of animals, especially the bison, was all done on foot to keep the stress to the animals to a minimum and again, sometimes that went well and sometimes that went south. Chasing after a herd of bison in a pen and having them all turn around and chase you. You found yourself running for your life! So yes, lots of stories.

MH: Can you tell me about any rescue/wildlife stories that stick out in your memory? 1825:

SF: Well I think that sometimes the things that happen earlier in your career stick with you more because you’re quite impressionable and it’s all new I suppose. Certainly one of the rescue stories that sticks with me is a crevasse incident that happened on the Athabasca Glacier where a German tourist fell into a crevasse and I was actually leading a training climb on a nearby peak with two other Wardens, and then we got a call that there was this rescue and they needed our assistance. So the helicopter was already in the area and there were a few people on the glacier already, initiating the response, setting up anchors and getting ready to send someone down the crevasse. The helicopter came over and plucked us off the mountain and landed us on the glacier and I spent the next three hours in the bottom of the crevasse trying to reach the person that had fallen in. I was one of the few people that could get in there because I was small enough and I guess that was kind of the beginning of a bit of a career for me in visitor safety because I would say, the majority of incidents that I responded to, especially in Jasper, were crevasse incidents and I was often the person down in the bottom of the crevasse because I was small enough.

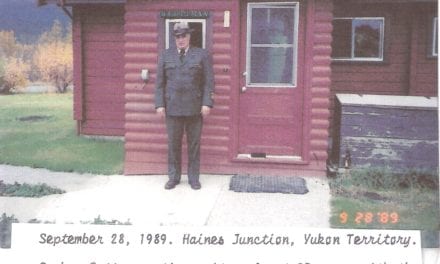

2025: I think another notable one for me was later in my career when I was working in Rev/Glacier, there was a fellow had fallen into a crevasse. He was on the outskirts of Kluane National Park and he was a sledder. He was outside the park but none the less, the expertise initially came from the park. The person unfortunately hadn’t survived but his family really wanted to recover his body and insisted that Parks or somebody try to get this fellow out. But it was not without risk because there was a lot of objective hazard, overhead hazard, it was in the middle of an icefall so it was very dangerous. A local Public Safety Specialist in Kluane did go and do an assessment and felt that the risk was too great for somebody who was deceased. About a week later a mountain guide had fallen into a crevasse in an area near Atlin, British Columbia, a few hundred kilometers away but still kind of in the same neck of the woods, unfortunately also deceased, so now we had two people whose families wanted to have them recovered. In both cases, families were willing to ask less trained people to go and get there loved ones. So in the end, we got a special team from the Mountain Parks to respond, Max Darrah from Jasper, Brian Webster from Banff, Chris Gooliaff from Lake Louise and myself from Revelstoke/Glacier went up north. We flew in an RCMP plane from Springbank Airport to Haines Junction, then got into a helicopter and flew to Atlin and did a significant rescue in very poor conditions, poor weather, poor visibility, flat light, late at night, lots of overhead hazard but we managed to do it and we got the guide out of the crevasse. Spent the night in Atlin and then the next day, we flew in a helicopter overland to the outskirts of Kluane National Park, and managed remotely to get the other person out of the crevasse, flew back to Haines Junction and then flew home. That was over four days. It was pretty big. It was in 2011. I have lots of stories, it’s hard to pick one over another.

2550: One notable one, again, early days in Jasper and myself and Steve Blake had just successfully finished our assistant guides exam. I was living at Sunwapta at the time and I hadn’t even had a shower. I’d been on this course for almost two weeks and the last week was up the Robson area, camping, and I had just got home, found out I’d been successful which was great, nice to know. I was just about to hop into the shower when I got the phone call that there was somebody in a crevasse (again) on the Columbia icefields. Steve was in the same boat. He may have had a shower or not, I don’t know but all of a sudden, the two of us were going to be the first team inserted to try and extract this woman who had fallen into a crevasse right underneath Snow Dome. So for context, if you are ever going up to the Columbia Icefields via the Athabasca Glacier, there is one spot that you do not what to spend any time and that’s underneath the icefall on Snow Dome. So what people typically do is once they reach that hazard zone, they move as quickly as possible to get past it. Once past it, you can take your time again. I’ve been up and down that glacier many, many times and that is the rule of thumb. Preamble to this rescue, is there had been a team of 4 people who had gone to climb Mt. Columbia and they had gotten up onto the icefield and had gotten snowed in for several days and they were on their way out. But they were not particularly skilled skiers and back in those days, most people were on old telemark gear (not alpine touring gear) and big heavy overnight packs. They started skiing down the headwall, roped up, as you would, because there are lots of crevasses in the area, but it was extremely challenging and they kept falling and if one person fell, then everybody fell. The rope would come tight, pull all of them over so finally one person had had enough and untied from the rope. As everybody got more frustrated, they untied from the rope until finally, there was only one person skiing down attached to the rope, and everyone else was just skiing down. When they got past the Snow Dome icefall, they convened and they were missing somebody. When they backtracked, it was hard to follow their tracks as the wind blew them in, but the person actually had a whistle and one person had strayed a little further and fell 50 feet down a crevasse, landing face down on a snow bridge with her pack on top of her, but at least they’d found her.

Wonderful stories and overview of a fine career. Also an excellent perspective of the times when the Warden Service exuded pride and professionalism and as noted had tremendous esprit de corp. There were so many interesting characters, hair raising stories, and a cadre of living legends before things went to hell in 1999 with the officer safety issue. As so many of us who worked through that era have remarked, we had 20 years of heaven and ten final years of hell in our careers ! Great job Sylvia !