Park Warden Service Alumni Society of Alberta

Oral History Project Phase 14 – 2024

Interview with Tom Hurd

Powell River BC

Written by Tom Hurd, Edited by Susan Hairsine

September 2024

Hurd Family at Palliser Cabin – Gavin, Bronwyn, Tom, Eric and Brother-in-law Gareth – New Years 2009

Where and what year were you born?

I was born in Toronto, Ontario in 1957, the 5th of five children.

Where did you grow up and finish school?

I grew up in Toronto and finished my high school there, though my first summer jobs during high school were working farther north in Ontario as a canoe-guide at a kid’s camp.

Did you attend a post-secondary school/institution?

I started my degree in Biology at Lakehead University, in Thunder Bay Ontario, in about 1978. It was after a couple of “gap” years spent working at the Banff Springs Hotel as a Convention Houseman, followed by two seasons working in fire control with the Yukon Forest Service in Whitehorse. I transferred my degree to the University of British Columbia in 1979. I would spend winters at UBC and return to Whitehorse for the summer fire season. I completed my Bachelor of Science degree in Zoology in 1983.

Years later, in 1999, I completed a Master of Science in wildlife biology while working in Banff. We can catch up with that later.

How did you become involved with the Warden Service?

I was promoted to Fire Crew Leader in the Yukon Forest Service in 1979 and was able to continue to work in Whitehorse because I was backfilling for an incumbent, but in 1981 the Whitehorse position was no longer open and I was expected to report to Beaver Creek to assume my substantive Crew Leader position. Beaver Creek is a small customs town on the Alaska border. The place tended to have wettish summers and a pretty slow fire season. I thought it was going to be boring (no offence to any Beaver Creek’ers). I was prepared to go if I had to, but I was looking for options, when I saw an ad for a Seasonal Park Warden position. It seemed like a dream job, so I applied. I applied for a Seasonal Park interpreter job at the same time—hedging my bets. I got interviews for both. But there was a catch. The interviews were scheduled to take place in Haines Junction at Kluane NP Visitor Centre but I had just arrived up to Whitehorse from UBC and I had used my last dollar to drive my truck back up to Whitehorse. I was pretty much broke and planned to couch-surf with friends until I started work. Haines Junction was 160km away. My plan to get to the interview was sketchy but it worked. I had an unregistered 250cc dirt bike, given to me by a friend years before. It generally rode back and forth between Whitehorse and Vancouver in the back of my pickup truck. It didn’t get much use, and it was pretty beat up, but it seemed like the only possible way to afford to get to the Junction. I borrowed some cash, filled the bike with gas, strapped a spare 2 gallon Jerry Can on the back and headed up the Alaska Highway, which was a gravel road at that time, to Haines Junction. All went well until I was just outside Champagne First Nations village when the engine quit. I checked everything and pulled the plug; it was a mess with bunch of particles bridging the gap. I cleaned it up and managed to get the bike restarted, so I made it to the Visitor Centre, but I was a little windblown and greasy. I got called in for the interview just as I was about to duck into the washroom to clean up a bit.

That was where I met Lou Comin and Ray Frey. I thought the interview went OK, greasy hands and all. When I stood up to leave, Lou got up and opened the door for me, and just kind of stared through me as I exited. As he closed behind me I had a hunch that I had just landed a warden job. When I came back about a week later for the Interpreter interview, I had just finished the written part and came out of the exam room to see Ray Frey waiting. He asked what I was doing. When I told him he asked why I would interview for an Interpreter when I was going to be a Seasonal Warden at Nahanni. As you can imagine, I was instantly on Cloud 9, and I don’t remember a thing about the remainder of the Interpreter interview.

Which national park did you start working in?

I started as a Seasonal Warden in Nahanni NPR in 1981. When I got off the plane at Nahanni Butte, I was met by Lou and Tom Elliot. I couldn’t have hoped for better mentors to introduce me to Parks Canada. They were the guys that put the Warden Service into my heart.

What made you want to join the Warden Service?

My older brothers started taking me on Canoe trips to Algonquin Provincial Park in Ontario at a young age. I was maybe 8 or 9. Somewhere along the way my brother Rod, pointed out a Ranger heading to his patrol cabin with a canoe strapped to his jeep. We surmised he was going in for his two-week shift. I didn’t think there could be a better job than that. The trips with family members continued into my teens and I eventually got work at a kids camp in Orillia Ontario guiding canoe trips on the local Lakes and also up at Algonquin. I was hooked on the idea of living and working in the woods.

What different parks did you work in? How do they compare? Do you have a favourite?

I worked two seasons at Nahanni, then, in 1983 I transferred to Kluane. Having just graduated from UBC, Bronwyn (my future wife) and I spent that winter building a log cabin on a lot at Marsh Lake, just outside Whitehorse. During my second season at Kluane, I saw an ad for an Environmental Assessment position in Winnipeg. It was full time, and I needed the cash after spending 4 years as a student. Besides, Bronwyn had decided to return to school to obtain a pharmacy degree. We thought that she may be able to transfer her degree to the University of Manitoba if I got the job in Winnipeg. So, I got the job in the Prairie and Northern Region service centre, and that began 3 years in Winnipeg with me working first as an Environmental Assessment Officer, and later, a Park Conservation Planner for Ivvavik National Park Reserve where I was tasked with writing the Park’s first Conservation Plan. In 1987, a competition was posted for several permanent warden openings in the Western national Parks around the same time as Bronwyn finished her degree. I applied and, in 1988, ended up as a full time warden in Banff National Park at Lake Louise. Once there, I rotated through the basic functions Frontcountry, Law Enforcement, Backcountry, and Public Safety—I was lucky enough to work the last season the Warden Service was responsible for avalanche control at the Lake Louise ski area. I was welcomed to Lake Louise by some really capable people that showed me the ropes and made the transition pretty easy. These included Al McDonald, Glen Peers, Dave Norcross, Clair Israelson and Dale Loewen. By 1990, I was commuting to Banff to work in the new Resource Management shop being led by Cliff White. Around then, Bronwyn and I sold our Yukon place to make a downpayment on a house in Canmore. We married and welcomed our wonderful sons Eric (1992) and Gavin (1994) into the world.

With the new emphasis on ecological integrity in the 1988 parks act, several specialist positions were established, and in 1992, I successfully competed for the job of Aquatic Resource Specialist and in 1993 for the position of Wildlife Specialist. I continued in the Wildlife Specialist role until about 2005. During that period, I was granted a year’s leave to pursue a master’s degree at UBC, which I completed, while on the job, in 1999. The nearly 20 years I spent working in the Resource Management shop with Cliff White, Dave Dalman, and Ian Pengelly were easily the busiest and most productive times of my career. Under Cliff’s leadership, I felt we moved the needle significantly toward restoring the ecology of Banff National Park. Wildlife movement was improved and by establishing wildlife corridors and better wildlife crossing structures over the highway. Wildlife mortality was dramatically reduced as result. We established an important link between predators, prey, and ecosystem diversity and were able to begin to reverse the forest damage being caused by large predator-free elk herds that concentrated in and around built up area and that had also become a significant public safety hazard. Parts of this work were published in a paper by led by Mark Hebblewhite, a PhD student, where it was described as a trophic cascade.

Workmates Dave Dalman, Ian Pengelly and Cliff White – Clearwater 2009

In 2005, I began a 3 year assignment as the Project Manager for the South Okanagan Lower Similkameen National Park proposal. The overall task was to assess the feasibility of a national park in the region from socio-economic, ecological, First Nations, and public perspectives. I returned to Banff in 2008 and continued work to get bison restoration on the table as the next major restoration project. It was just entering the final planning and budgeting stages when I retired in 2012.

9. What did you like the best about being a Warden?

The adventure. Very few things about the work were “typical”. It could be isolated, dangerous, demanding, and cerebral all at the same time. You had to know your stuff and be self-sufficient. And you got to work with very capable people. Later in my career I appreciated being able bring data from ongoing wildlife research and monitoring work to park management meetings. Seeing the information used to make better decisions was pretty rewarding. I also liked that the organization really valued its people. Being allowed to go back to school to improve your credentials I thought was indicative of a pretty forward-thinking organization.

10. What did you like the least?

I cover that in the next question.

11. What are the more memorable events from your Warden career?

One of the most memorable events was also the most frustrating. This was dismantling of the Warden Service as the result of the law enforcement fiasco. I agreed that our law enforcement function needed to become more professional and that carrying sidearms was warranted, but I did not agree that all wardens needed to be armed and trained to that level. I had hoped that we would continue along specialist/generalist lines with better armed and trained law enforcement specialists becoming part of the mix, much like the current U.S. Park Ranger model. There was no need to eliminate the majority of the Warden Service, and revise job titles and expectations. I believe the organization is still trying to find its way forward, as a result of the knock-on effects of that decision.

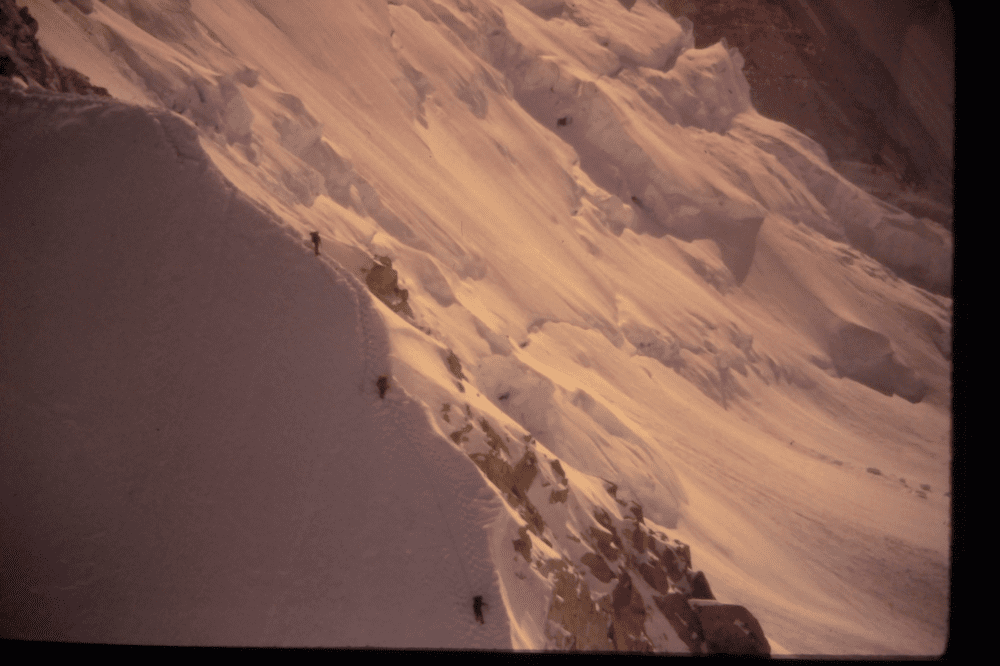

Moving up to high camp – Mount Alverstone, Kluane, 1984