BW: It wasn’t a person; it was an entire department. But at any rate, the weather stations, they were really a great addition to our forecasting capability.

(Tape 40:45)

SH: Do you want to add anything to your main duties and responsibilities over the years?

BW: Well, I was lucky I had a rounded career. I started in Waterton, which had everything, and I had a good backcountry stint and really enjoyed that. Then in Visitor Safety we still did a little bit of everything for a while. That was a great thing where you trained everyone in the park with a little training, and then we had a national training component too.

SH: Did you get up to the north?

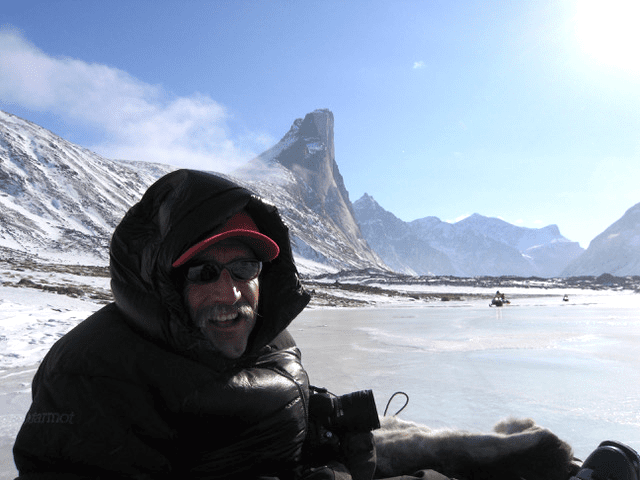

BW: Yes, I had trips all over the place. I never got to the east coast unfortunately, but I was in Bruce Peninsula and Pacific Rim and had several trips up to the Arctic, Ellesmere Island and two or three trips to Baffin Island and one trip over to Bylot Island, so I got lots of nice trips up there.

Self-Portrait. Auyuittuq NP near Summit Lake, Photo by J. Bradford White.

One It’s different just working with the Inuit people. Things are just a little slower; you bring your southern kind of speed up there and you have to learn to slow it down.

We did get some fun trips for sure. I remember one trip we did in Auyuittiq. We did a great trip from near Windy Cabin.

Mt Thor, Auyuittuq NP. Photos by J. Bradford White

The one trip that really stood out for conditions I think, Lisa came up to help me with that, Lisa Paulson. You know often you get spring conditions that are not perfect conditions and there is not great snow because it is polar desert and all above treeline, but we did a ski trip where we up around Mount Asgaard, we went up the Parade glacier and around and camped, and then we came back down the Caribou. We were out in a storm, and on the last day it was great skiing back down the Caribou beside Mount Asgaard, we were skiing in 30 centimeters of light, dry powder all day long right by those giant granite faces which is mainly unheard of.

That was very spectacular, the mountains. Pond Inlet, again the mountains are much more rounded, but I had a beautiful trip up there one time where we skied a whole bunch of peaks. You could ski right to the summit of these peaks and ski right off the top. I was lucky because I got those trips for sure.

On the Pond Inlet trip we made some igloos and one of the Innuit Wardens said that culture dictated that he was supposed to have learned to make an igloo before he was married but that he hadn’t and he already had two kids. I always half-joked that part of what I was doing up north was teaching Innuit to build igloos, but the sad part was the culture was changing so fast.

So, the training for other regions was a big part of it, but there was also training for all the different local parks, all the different people and we still had the tradition of the regional schools that went back to the days of the first visitor safety specialist or alpine specialist, you know Willi and Peter. Even before him, Walter Perren.

I actually met Walter when I was young. Here’s a story. When I was a kid at Sunshine my dad and brother decided, they were going to hike up to the Goat’s Eye and they didn’t show up for dinner. So, my mom takes me down in the truck and we’re looking for them with binoculars and she says “Can you see a couple of things that aren’t moving up there?” I said, “Well I don’t know, maybe.” and anyways she decides we better call the Warden Service.

We went down to the Healy Creek Station and I am pretty sure it was Earl Skjonsberg that was involved, and he gets an old Bergans rucksack, and a pair of boots and a rope out of the shed there but calls Walter Perren and eventually we end up with a bunch of Wardens on the side of the road that are ready to do a rescue. About then my Dad and Cliff came staggering up out of the bush. It had just taken a lot longer than expected, and the two rocks on the hill were still not moving. And then of course I went to school with his kids but that was after Walter died. I’m not sure what year he died …. ‘67 or something like that. But his kids grew up in Banff.

SH: Yes I did Peter’s interview; it’s quite good and on the Warden Alumni page. It’s a really interesting one.

BW: I imagine. He and Tm came as close at it can come on the fall off Mt. Logan.

SH: When you were doing schools did you get up to Kluane?

BW: Yes, two trips in Kluane. I never climbed Logan, but we did a long ski traverse up the Dusty Glacier and climbed some peaks and we also did another trip where we climbed Queen Mary from the glacier camp.

SH: What would you have been doing at Bruce Peninsula?

BW: They’ve got a bunch of sea stacks that go down into the peninsula there so there’s a little bit of climbing but often more it is people that kind of scramble around and get in trouble so they need some rope rescue capability. They had a few responses, not a huge demand for response. But shortly after I went, I think they decided they were going to get the Bruce Peninsula fire department who had some vertical extrication gear to do it. But basically, we were training technical rope rescue on the cliffs.

Some of the stuff in the Broken Islands…we had a multi-agency response practice where we had the Coast Guard involved, and we put the patient, in the middle of this big cliff and had to do a rope lower down to extricate them and package them and then lower them into one of the Coast Guard rigid hull inflatables on the cliff edge with the sea swell running at about 8’ that made it tricky. We did a couple of tension lines across surge channels where you set up a high line to lower the rescuer straight down into the water because people fall into surge channels and they have to be pulled out.

SH: I’m not sure if you did any jet boat rescues, but do you want to talk about jet boat stories? I seem to recall one.

BW: There’s more than one jet boat story if you go back. I’m pretty sure it was Norcross and Ledwidge that sunk one in Lake Louise. There was one in Jasper. I do recall driving that old Lake Louise jet boat through the Lake Louise rapids. The three standing wave were like bang, bang, bang and on the third wave at full throttle the steering wheel broke off. Now the steering wheel is down in the bottom of the boat, and I’m trying to still trying to get through the rapids and fish that steering wheel up with my feet.

In Banff Park we did have some water rescues in the park. I think we had more in Jasper, but certainly there were some water rescues in Banff, so we were trained in swift water and it wasn’t something …. I wasn’t really a good swimmer when I started but I remember the first training exercise where we were dressed in dry suits. Kiwi (Gallagher) was involved, and I was out in Kananaskis Country. He said “Okay, we’ll just dive off this cliff into this Grade 3 rapid and swim.” It was a little outside my wheelhouse but after a few years of doing that, it actually got to be pretty fun and after a while and I learned a little more about rafting and whitewater canoeing and a few other things along the way and I got to be a little more comfortable with swift water. And I was more comfortable driving the boat because I’d been driving a ski boat for years.

Swift Water Rescue Practice, Kananaskis River.

Brad rescues a boy from Marble Canyon.

The jetboat sinking in Banff was…there was a deal where there was something wrong with the fuel gauge sending unit, so we weren’t getting a good indication of how much fuel there was in the boat, and you don’t want it to run out of gas, obviously. But it went on plane better if you put gas in the inboard tank because the tank was in the front. At any rate there was a training exercise with Kananaskis and they wanted to use the boat, so I said “Just run it off the spare tanks because it’s not really perfectly operational. There’s no gas gauge that works.” Anyway, they decided they’d run it off the main tank for better performance , and they ran it for a full day the first day, and it did not run out and then filled it up with gas for the next day. But then of course they used a little bit more the second day. So, when does a boat run out of gas? It’s going to run out of gas like literally about 200 feet above a big turn that has a log jam on the sweeping outside corner. So, the boat ran out of gas, and they were being swept into this log jam. It sounded like it was a very close call. I wasn’t there but they did manage to get it hooked up to the auxiliary tank, but they couldn’t get it started right away because they didn’t realize it was still in forward and it only starts in neutral, and it had run out of gas when it was in forward. Eventually the boat was swept into the log jam. I don’t know what all went down. It sounded like one person jumped out and nearly got swept under the logs, and then they got a line on it or something and tried to drive away with the line on, and it sunk the back down, underneath the water. But anyway, whatever happened the boat swamped, and the boat sank.

SH: We got a new jet boat didn’t we.

BW: Well, there was a big deal made out the sinking of it as a close call. Nobody was allowed to do anything water related until it was investigated. The Chief, Bill Hunt, and Marc Ledwidge went out to look at it the boat the next day. It was washed up on a gravel bar and they went and looked at it. It was salvageable but there had to be an internal review of how this near miss had happened and meanwhile the boat is there. So, I said, “Well at least you built a deadman and tied it off.” But no, they had left it untied, and the water has come up, so we go look and sure enough there’s no boat where it was; it had got swept downstream. It lived underwater for a while and then it showed up in the river and it was quite a long time later. I remember JP Kors and I were supposed to do a training day and I said, “Well somebody has to do it, so we better do a water rescue day and go get that boat.” So, we go out and get our boat. And Frank Burstrom had one of these chainsaw winches that you use for building log places that he lent us and we had a bunch of pulleys and ropes. So, we go out there and we’re walking down to where the boat is, and there’s a bunch of guys there.

They’ve got some straps and ropes and batteries and winches. We said, “What are you doing?” They said, “We came to get this boat.” We said, “Sorry it’s ours”. So, we nearly lost it but it was tough to get it out. It had been living in the river for the summer and the whole bilge was filled with gravel. Eventually we got if flipped over and had to tear some of the floorboards out to get some of the gravel out. We managed to get it floating eventually. It was impossible to tow it upstream, it was so heavy, but eventually we got it downstream with Mike Koppang from K- Country and winched it out. So that was that. Nobody drowned. So, we did water rescue.

My wintertime responsibilities were mostly in the avalanche world. That was sort of my main interest, skiing and avalanche forecasting and patrols. Over the years I got involved with quite a lot of different stuff, working on some of the projects with you like the North America Avalanche Danger Scale project, the conceptual model of avalanche forecasting.

SH: You were always a real favourite to go teach avalanche courses for the CAA (Canadian Avalanche Association).

BW: Ya, I’m still teaching. I am just back from Sweden. I went over there and did a Level 2 exam for them. I’ve been over the last two years, did the course and then the exams.

I was working when the Strathcona Tweedsmuir accident happened. I didn’t end up going to the site thankfully. That would have been pretty tough with those young kids, but Tim (Auger) and I came in on our days off and we helped set up, you know, just did some of the overhead stuff. Tim Laboucane was involved, and we were getting people who could do PR (public relations) work, somebody that could speak to the press, and a place where you could get the families to come, a reception centre, all of the rest of that stuff, where are the bodies going to go, and on and on, the stuff that has to be done in the background.

At any rate what came out of that was Grant Statham was hired and we worked on the North American Danger Scale and the conceptual model, but we also worked on the ATES (Avalanche Terrain Exposure Scale) rating system and some other initiatives.

SH: Yes, so much came out of that.

BW: Yes, trying to implement the recommendations that came out of the study. Then at the same time I was working on the very first web-based forecast. I got a bunch of help from some of the IT folks in Banff. I can’t remember what it was called, it was some Microsoft software where you could actually write the forecast on a webpage. It was more programming than we would do now, you had to write the code for the page and make it work. So ya, we got the first web-based public avalanche forecast going. At that time, we were working with Karl Klassen at the Canadian Avalanche Association, trying to really build a better product for what we were putting out to the public, and then when Grant got hired, we put out the more icon based, risk based, multiple layers of communication forecast. The forecast evolved. So, there were lots of changes in the avalanche forecasting world. That’s what I did mostly in the winter. Of course we were still doing rescues. We had some funny winter rescues.

I remember one …. so … the way we worked it in Banff, we ended up hiring a bunch of really talented guides that were already guides, and that was part of the great warden schism when we stopped being wardens. We can talk about that when we get to this point. But we always had one on as sort of rescue leader on call, or incident commander (I.C) on call as we transitioned more to the IC system. I got this call one day when I was on call. “There’s somebody who’s fallen into Johnson Canyon”…this is wintertime… “And they’re under the ice.” And they can hear him yelling for help under the ice. So how is this going to go? You really don’t know how it’s going to go right? At any rate we had lots of responses at Johnson Canyon, and by the time you get a helicopter there and stuff it was quicker to get somebody on scene and have a backup team that would bring the extra gear and the helicopter if you needed it. Because there are not that many places you can actually sling in and out of there. Sometimes you needed some technical gear on the bank.

At any rate I’m by myself, because usually you’d only have one person on call, and I went running up trail while the rest of the crew was mustering. I get pretty close, and some folks on the trail said, “They got him, they got him out!” So, I said, “Oh that’s great!” so I could pass that on to the team anyways, and I go to get more details. So I go around the corner and they’ve got this guy lying on the trail and he’s soaking wet and cold. I look at him and he’s an assistant ski guide. I had just taught him on a weather course. He said, “I know you.” And I said “Ya, what are you doing?” He said, “I just thought I’d go for a walk up the canyon, so I had my crampons and my ice ax.” So, he started walking up the canyon and he got to a place where the water is quite fast. There’s a shelf of ice that had formed higher than where the water was, because the water had dropped. Anyways, he fell through. So, he’d dropped through and he managed to get his ice ax planted into ice so he’s hanging with one arm on his ice ax and the rest of his body is underneath in the rushing water. So, he’s hanging on and he can’t pull himself out. The force of the water and the fact that it’s kind of over his head because the water is a little bit below where he’s dropped down. He can get his chin up and get out of the water but he can’t get out and eventually he just goes “Ya, I didn’t know what was going to happen, but I had to let go, I couldn’t hang on anymore.” So, he gets washed down and he bumps down underneath the ice until he could stand up, and now he’s standing up in chest deep water and there’s a little bit of an air spot, but it’s solid ice over his head, and he’s standing in this freezing cold water. So, he was banging his helmet on the ice and screaming for help and that’s what the call was. At any rate he realized he wasn’t going to be able to stand there very long in this freezing cold water, and he thought he could see a little bit of light between the water and the ice, so he tried to go downstream and it worked. He managed to go downstream a little bit more by holding his breath and then he got to a spot where he got out of the canyon where the creek spread out, and there was a hole. So he managed to get to the hole and then some people from the shore managed to grab him and pull him up on the trail.

SH: Talk about lucky.

BW: Yes, he was lucky. When we started pulling all this stuff together, that was in winter, in rushing water, under ice, that could have been very tricky, but it all worked out.

We had another one like that as I recall. I could probably go on all day as one memory triggers the next. I can’t remember exactly who the team was in the office. But it was right at the close of the day and we got this call. Somebody has just fallen in Bow Falls in winter. They walked over to where the rushing water is, where the water is rushing over the falls, and they fell in. The guy was from Saskatchewan. So, this is a big deal, so we grab all our ice rescue gear, our water rescue stuff. At least you know Bow Falls isn’t totally frozen underneath, so he has at least a chance but it sounded dicey.

We get down there and the ambulance is already there because they’d called 911. In those days we had already gotten rid of the Parks Dispatch as the contact for emergencies, so people called 911. I’ve got a story about that too if you want. But we get there, and the guy is wading out of the river and his face is all scratched to heck but he’s pretty much fine. His wife is like beating him up. “You effing idiot, I told you not to go over there.” So, what happened he just went to the edge and slipped and went “boom” under Bow Falls with his face up, so he got scratched up on all of the ice. So, he went under the ice and got washed down Bow Falls and when he got to the bottom it wasn’t that deep and he managed to get his feet and staggered off to near the shore, and was fine. So, he went under Bow Falls in winter and survived, under the ice.

SH: Wow, that’s crazy. (Tape 23:23)