BW: I did a ski school out of there one time. I understand the cabins and trails are in bad shape now there. That’s the real end of the era when you think of it. The backcountry isn’t going to change whether you have those cabins or not but wasn’t it nice to know that there was somebody there who actually cared about that part of the world and was looking after it.

I think we lost a lot of sheep out of the north corner of Banff when we were no longer doing boundary patrols. How effective we were when we used to do those boundary patrols, I don’t know but we did catch people poaching. In fact, I watched a couple of guys who were going to poach an elk one night on the Clearwater. When they were talking about whether they could make a shot or not I just rode over to them. I didn’t even have a rifle with me, they both had rifles, but I was pretty sure they weren’t going to shoot me. That’s the real big change that we had.

SH: What about the Warden Service was important to you? Protecting and preserving national parks, keeping people safe? You were Mr. Everything and doing all those things.

BW: I think that goes back to the earlier thing. You were expected to do it all. You weren’t a well-rounded warden in the early days if you couldn’t ride, ski, if you couldn’t do a little bit of climbing, if you couldn’t fight some fires, work with wildlife and do law enforcement. And yes, you could be better at one thing than the other, but the real thing was that you were expected to be a well-rounded outdoorsman was what it amounted to. I remember Dale Loewen when we started letting volunteers in the cabins, people doing studies and whatever, would show up there. He’d say, “There’s nothing but herbal tea in there and if they do have bread, it’s bread with nuts in it.”

SH: I think Dale was one person who never did embrace computers.

BW: Yes, you are probably right, and the other one was Frank Burstrom. Maybe he did a little bit at the end. I didn’t see this, it was a second hand story but Frank called somebody and said “Can you help me with this computer?” “Yes, what is it?” “Well, it’s the emails. How do you delete emails? Can you delete them all?” So, the person said, “Ya you have to do this.” So, Frank said “Great, go ahead and do that” and they deleted them all. Okay, thanks. That’s what I needed.”

SH: Are there any legends or stories associated with the Warden Service that you can share? I know you have great stories, even ghost stories.

BW: I don’t know. I worked with Willi in Waterton, and we ended up with this person whose name was Lou, and Lou turned out to be a woman, which in those days the Warden Service was quite misogynistic. I was lucky I worked with some really capable strong women that started with the Warden Service early on. Diane Volkers or Sylvia Forest or Lisa Paulson or a lot of the other women that I worked with were just part of the team and didn’t expect to be treated differently and you didn’t treat them differently. Maybe we did treat them differently, we just didn’t realize how we were treating them differently but anyway, they made great members of team.

Anyhow Lou was not very good. It turned out she had lied on all her applications, and she had been fired from her last job and they didn’t check her references and stuff. Early in the spring, we got this spring training with Willi, and we were going to go up Mount Crandell I think, beyond the Bear’s Hump. It was basically like a fourth class walk to start with and then it was steeper at the top. We’re walking along and I notice she’s walking on her toes. I said, “Walking on your toes is probably not great. That’s hard on your calves. You won’t be able to get along all day walking up steep hills.” She said, “No, no I’ve tried it both ways and this is better for me.” I said “Okay”. It turned out she was deadly afraid of heights, and we got along the route where there was just a little bit of exposure and then she couldn’t walk anymore, and she was starting to want to crawl. So, then Willi came back, and Willi didn’t have much time for anyone who wasn’t capable, including his own daughter. I remember him yelling at Suzie on Edith Cavell on the face, “You’ve got to get going!” And (his son) Fred, he was hard on Fred too. At any rate he comes back and looks at Lou and he says, “Basically you got to be able to walk for fuck sake if you want to be part of the Warden Service.” So, he takes a rope and he ties a rope to a tree over here, and a rope to a tree over there and has her tied in the middle and says you just sit there until we get back.” So, he just tied her up so she couldn’t get in trouble, and we went to the summit of Crandell, and then came back down and picked her up on the way back home.

SH: Wow, you wouldn’t do that now.

BW: No, you certainly wouldn’t. I was doing lots of warden schools and it was always a perk if we could get a helicopter lift or something. The joke in those days was the five W’s of the Warden Service were “We won’t have to walk will we”. After we stopped doing warden schools and the wardens were no more, the five W’s of the Warden Service were “We were Wardens once weren’t we.”

Willi was really one of my mentors and he was tough. Freddy was a good friend of mine and Freddy and I worked together at Mike Weigele’s Heli Skiing. Then we had a fatality at Weigele’s and we had some issues there. Well, there was a lawsuit, paperwork that had been changed and a bunch of other things I won’t get into but I went to work for CMH and Freddy stayed on. He’d kind of been drifting in Jasper but he was just getting ready to start down the road to becoming a guide. Anyways, I got in a bit of trouble one day there for skiing off the standard line on this really nice north facing glacier but it ended in a big terrain trap with a terminal moraine. I remember the call the next year because I was in the Gothics. “Can you guys be on standby for an accident in Blue River?” and then I got on the phone that night and found out that it was Freddy and it had been on that very line that I had been a bit brash in skiing the year before before. The whole thing avalanched and he was killed along with most of his group. So that was one of the last things that Willi had to do was come as an organized rescue team from Jasper and dig out his own son.

SH: So, Willi was a legend. Who else would have been a legend for you Brad?

BW: Peter Fuhrmann was a legend in a different way, but he supported me and certainly Clair supported me and Tim supported me when I was starting to go down the road of becoming a guide. Peter was famous for never starting til way late. One time we were going to climb the East Ridge of Temple with half the group and Peter was going to climb with the other half up the Anderson couloir, so we go “Well we got to get up early and get going.” So, I’m on the eastern side with our group where you climb the east buttresses which is rock, and Peter’s going to go up the Anderson couloir which is a nasty piece of steep ice and snow that ends up in the same place where we are going to meet up and camp overnight, just below the black towers. We get to Lake Louise and go around to Gord Irwin’s trailer because he’s going to be with our team, and knock on the door, but Gord’s not even up yet. “Come on Gord, we gotta get started early here.” So, we get a coffee going while Gord gets up. I don’t think Gord drank coffee, but we managed to find something to drink there anyway and still made a decent start. Then off we went, and we got to the top of the east buttress, and all is good and we’re getting near to where we want to be camped and where we will meet the other team, so we get on the radio and we’re calling Fuhrmann. “How are you doing?” He goes, “All good, we’re just leaving the trucks now.” “What?” So, he hauled a bunch of people up that colouir in the middle of a pretty warm day with rocks falling down on either side. At any rate Peter had a good mountain career but he was also known for being a late starter. Fuhrman forced marches as they were called occasionally.

Of course, the greatest thing that Peter did was get the heli sling program going and start the pilot testing so that all of the pilots we used as rescue pilots had to go through a Park’s pilot test. In the later part of my career, I got involved with doing a bunch of those tests. We had such a group of the greatest pilots that lived in Canmore and were happy to do rescue work and most of them were heli ski pilots as well. I think they ended up being a lot of times, the unsung heroes of the job we got done. I always used to say about an article on a rescue: “It’ s not Alpine Helicopters that flies us to those things, it’s the pilots at the controls” and we really had some awesome pilots over the years starting with Lance Cooper.

I recall early in my career Peter put on a rescue practice and there was some politics at the time because Quasar had just come in as low bidder for the rescue ship on standby, and Quasar was a bit of a fly by night company. They ended up actually going out of business not long after that, but they had some good pilots working for them. Anyway, Peter put this show on where we were doing all these rescue stations right in front of Chateau Lake Louise, from Mount Fairview and cross over to the other side to the Big Beehive, right in front of everybody at the Chateau.

I was in charge of one of the stations, as a young seasonal interested in climbing and the deal was that people got moved from one station to the next station, get off, get on an anchor and then eventually fly down, so it was like a bit of a circuit. Peter had decided he was going to use some of the flying that was done by one of the pilots as a reason to try to get rid of Quasar. It happened that he chose the station where he put me at, where he was saying the pilot was flying with their rotors too close to the cliff and stuff like that. So, there I was in the middle of a political maelstrom being the eye witness to this, well it was mostly politically motivated. The flying didn’t look that dangerous to me but then our station was…sure the rotors were close to the cliff in some places but that’s the job those guys have to do. But as a young seasonal having to write letters to the Superintendent and writing about how this thing went, you kind of walk a knife edge of being politically correct but not being on one side or the other. The dust settled and we had a couple of good Quasar pilots although I did crash with one a year later when Quasar was working with Weigele, which was a mechanical thing. That’s probably enough about pilots.

SH: Is there anything about the Warden Service as you knew it that you would want future generations of Wardens to know?

BW: Future generations of what are now called Wardens that are armed dog catchers mostly? …I shouldn’t say that but now that we’ve decided, based on the fact that Wardens were in the Parks Act so it would have meant opening the Act and changing it, so to be a Park Warden or a Peace Officer was enshrined in the Act. So now the only Peace Officers who do law enforcement are armed and are Park Wardens and everybody else is called something else.

The thing that you want to know is if you are interested in law enforcement. I think that there is a career there in law enforcement that allows you to still use horses, get out in the backcountry, protect the wildlife, do all the things you think of as a game warden. Those are the wardens of the future. But the parks are still there and there’s lots of work there. So, if it’s Resource Conservation Officer or whatever the new term is, the terrain hasn’t changed. The issues of managing that terrain from encroachment and just trying to maintain this balance of ecological integrity against use, those conflicts will be there forever. Monitoring of the wildlife. The bison introduction. I think they will probably continue to be more serious as time goes on.

There’s work … my nephew Pete worked on the bison project and other folks like aquatics that have managed to find a reason to get out of the office and into the field. My other nephew Charles worked on the backcountry trail crew with the horses there and they were out in the park and doing trips. But I feel sad when we don’t have enough money to hire game guardians anymore because nobody can see how that’s something serious that needs funding. The most concentrated bunch of grizzlies in a front-country setting in the busiest park in Canada and we can’t afford to try and save them. ( A white coloured grizzly sow and two cubs were killed on the day of this interview).

SH: Like Living with Wildlife.

BW: Yes, like Living with Wildlife folks. So, there is that disconnect. That was always one of the things I disliked about working for government. It seemed there was a giant disconnect about what probably would be the right thing to do and what we were able to do because of bureaucracy. The inability to get funding, the inertia, the fear of looking bad or making a controversial decision, all the things that prevent things from getting done instead of getting them done. As I mentioned earlier, I think probably one of the bigger problems with the Warden Service is there was too much of a strong force from the ground up that understood what needed to be done that often was at odds with upper-level management. It was one of the things …. people who want to have the power are afraid of people that hold some power.

SH: What made the Warden Service such a unique organization?

BW: I’ve touched on this quite a bit. But the Warden Service when I joined, first of all, it was a very young group. There was a huge amount of hiring going on so a lot of people in their early twenties with lots of energy and ideas about how to make things better and there was some money available to do that as well. When you think about the growth in the 70s in the whole avalanche protection program in Parks, that was pretty neat. Keith Everts was involved, building log cabins at the ski hills, and promoting avalanche research centres and trying to develop early RACs (Remote Avalanche Control). The first RAC’s that were ever built in Canada were put in on Mount Bourgeau.

Then there was a team. I think the biggest thing that Willi always said was “Ya I can do it but to get this done we gotta be a team.” and he was one of those guys who recognized where people had some skills. Okay, you do that, we’ll do this, and we’ll get better as a team. I think a lot of the guides I worked with over the years, are good at empowering a group of people to do better where people have abilities that are recognized and encouraged.

At the time when I joined the Warden Service that was very much the way. You think about the boom in Visitor Safety in Lake Louise at the time under Clair. The amount of work that was getting done and it was not really being overseen at the micro level. You know how to do that, that’s your job, go ahead and get it done. And there was a lot of freedom with that.

SH: Do you have any lasting memories as a Warden? Favourite, park, cabin, horse, trail, etc.?

BW: I managed to get a few good horses over the years. There was a horse named Jelena in Waterton. She was a palomino mare, she had mostly quarter horse in her, I think. I don’t know where she came from. In those days we kept our horses at Waterton over the winter and there was some different stock from the ranch stock. They never went back to the Ya-Ha-Tinda like a lot of the other park horses. I remember trying to chase buffalo and horses off her. She was super agile. I had a really nice colt too in Lake Louse. That was after the Ya-Ha-Tinda got the Morgan stallion. His name was Snip and he had some issues to start. He’d been trained … well he just had some issues, but we kind of got those sorted out and I had him for two summers I think, and he was really good by the end. Unfortunately, he died of colic the following summer after rolling down a bank with another warden and twisting his gut.

SH: What was your favourite cabin, or you could give me your top three because I couldn’t narrow mine down to one.

BW: I think Scotch Camp was everybody’s favorite just because you sit there, and you’ve got that beautiful pasture out front. In the early days there would be four or five hundred elk out there with your horses and the sun would come up on the deck, it really is the gateway to that part of the north park. I loved being at Indianhead, but the Indianhead house kind of had that haunted feel to it and all of that and it was a house and not a log cabin. It would just feel spooky when you went in there, but I just loved that part of the world. I loved being there, there was big loops you could ride from there, lots of game and you really felt that you were isolated out there. Cyclone was another favorite.

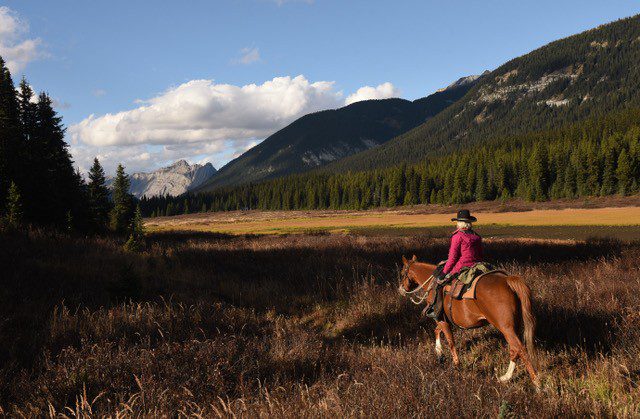

Donna White on a back country horse trip to Palliser with Brad. Photo by J. Bradford White.

Clearwater Lakes cabin was interesting. One of my goals one summer was to paint the interior of Clearwater Lakes cabin. I don’t know if you have ever been in it, but it was half pink and half green inside. So, it was painted by Jim Rimmer and he got some free paint that was left over from the painters in the paint shop or whatever, so he decided he was going to go paint it but he was colour blind and did not know how weird it looked. One of my goals was to paint that cabin. I looked at that and said “I can’t do it. I’m not going to paint over a pink and green cabin that was painted by Jim Rimmer. This is too much history here. It’s so stupid that it’s pink and green inside and I’m not going to be the one that covers over Rimmer’s paint job. I got a ‘less than satisfactory’ on my year end evaluation because I never painted the cabin, but I was proud of that. I used to visit Jim when I went to Waterton because he’d moved down to Lundbreck and was on the side of Highway 22 so I would stop in and see him. He had this old bear trap saddle that he’d gotten from somebody, with giant hooks. You would hook your legs into the saddle and there’s no way to get bucked out. A friend of mine named Juri Krisjanson was a guide at Weigele’s. He was a climbing partner of Yvon Chouinard that ended up working for Weigele as a ski guide. He used to be in Jackson Hole. But he owned a really nice little piece of property just off the Oldman River. But he had this horse that was kind of rank. Jim said, “I can break this horse for you.” So Juris takes this horse down to Jim. Old Jim Rimmer folds himself into this stupid bear trap saddle on the back of this horse all by himself in this little corral that was by the barn near the trailer he rented on this place. The horse bucked him right through the fence and he managed to crawl to his truck, and he drove to the Pincher Creek hospital. He walked in and sat there for a while and finally they gave him an x-ray. They came running out and said “Don’t move, don’t move!” I saw him in Waterton some time after that. I said, “How are you doing Jim?” He said “Not too good, not too good. You see I’ve just broken my neck.”

SH: Oh, that’s funny.

BW: Yes, I digress.

SH: We were talking about cabins.

BW: Yes right. So, I did know Jim. Come full circle in the Warden Service, Max Winkler calls me one day and says “Brad somehow I’ve become the executor of Jim Rimmer’s estate” which probably amounted to a bunch of old pictures of Spook his bull terrier, his old revolver from the Palestine Police, and a couple of half mickies of brandy in his trailer, because he lived on squirrels. But anyways, Max had his ashes so I said “Okay, what can we do?” So, I went to see Ian Syme and I said “We gotta do something with Jim Rimmer’s ashes right?” So we got a helicopter and we got Max to bring the ashes up from Pincher Creek one weekend, and Ian and Moe Vroom came, Bill wouldn’t come because of his cancer and we went out and we stood on the porch of Clearwater Cabin; with the pink and the green walls I might add, and we spread some of Jim’s ashes out in front of the cabin there, and then we flew up Indianhead Creek to another little lookout where I liked to sit and watch the sheep and put the rest of his ashes there. (Tape 32:52)

SH: What aspects of the Warden’s job do you miss most?

BW: I miss the team. That was the great part, working with that crew. You had a bunch of good guys and gals that you could depend upon. It’s the same with every job. You kind of just get used to seeing them every day and to interacting with them. Especially back when we had the schools, from all the parks. You got a chance to see everybody all the time. Now I don’t see most of those people very much anymore. You run into a few here and there.

SH: Yes, I miss that too. It’s nice in this valley here because I still hang out with some of them which has been wonderful. They’re a very unique group. What year did you retire, not that you’re retired, but what year did you retire from Parks and what do you enjoy doing now that you are “retired?”

BW: I think it was 2017.

SH: Yes, it was 2017. We had the same retirement party. So why don’t you list the million things you are doing in retirement.

BW: Well, I’m not doing millions of things but I am still working for the CAA (Canadian Avalanche Association) and just got on the Board of Directors with them, and I still teach quite a few avalanche courses, and I still involved in guiding and avalanche forecasting world quite a bit. I work with a company called Alpine Solutions and do a bunch of forecasting work for them. I just finished up a project doing avalanche forecasting for LNG pipeline that goes into Kitimat, so that was an interesting thing to work on. Trying to get a pipeline through the Coast Range which has some really steep mountainous terrain with some real avalanche problems, and lots of snow, lots of bad weather.

In the end the job’s the same. You’re trying to forecast for the likelihood of avalanches, you’re opening and closing terrain, and throwing bombs out of a helicopter. It’s all the same work, it’s just quite a different clientele than you’re used to when you are doing a road control program or a guiding program.

Another neat project I got involved with is an avalanche safety feature film. It was filmed by the Sherpas and funded quite a bit by the Utah Avalanche Center. Both of my daughters and myself are featured in it. The plot has them coming in to visit me at Skoki and then I am talking with by the fire with Ginny about keeping safe in avalanche terrain. This is juxtaposed against the stories of to two other tragic avalanche incidents where the survivors tell their stories. Check it out: “To the Hills and Back”, Sherpa cinema, it won quite a few awards.

SH: I know you tragically lost your Hawaii restaurant in the fires.

BW: Yes, the big fires in Maui, that was a devastating thing there. Over 2000 structures burned down including the commercial building I was a partner with my brother and sister, but who knows what will happen there because everything that happens in Hawaii happens on Hawaii time.

SH: Are you still active at the Whyte Museum?

BW: No, I timed out of the Board at the Whyte after 9 years as chair, and haven’t been involved too much in the last few years. But I have more time right now. That’s why I stepped up to be on the Board of the CAA.

The other thing I’ve been doing in retirement is that Donna and I bought a little ranch. My uncle took over a quarter section on the Ghost River, that my grandfather on my mom’s side had bought. Once my grandparents died my uncle got it and he moved out there when he retired and built this beautiful timber frame home. It was all built out of reclaimed fir from the Didsbury grain elevator. So they knocked the grain elevator down and it came on these flatbeds, and I helped him. We spent many days trying to find nails in these old 100 plus year old fir and milling boards on his Wood-Mizer mill. The house is beautiful. Everything is all hand-built timber frame. It’s a really nice quarter on the south side of Highway 40 and the south boundary is a half mile of the Ghost River.

We’d always had our horses there since I was a kid, and I started riding there although I also rode at Sunshine a little when I was a kid too. One day Donna and I were out there, and my uncle Bob says, “The ranch is for sale and people are coming to look at it in an hour of so.” I said, “I always thought it was going to go to my cousins ,but I said I thought if you were going to sell it, you would let me know”. He said, “Well I just let you know.”

So, Donna and I looked at it and there’s a lot of family history there. My sister Tristan and my daughter Katy were both married there, I grew up there and had just about every birthday I ever had there because my birthday falls at Thanksgiving. We looked at our finances and we got it appraised so we knew exactly what the value was and there wouldn’t be any hard feelings in the family that we were taking advantage. So, we ended up buying it and now people ask me what I do, and I say “I work for my wife. I never have to leave home to find work, I just have to leave home to find work to pay for it.”

SH: You’re funny. It’s a stellar piece of property and, you’re about to be a grandpa!

BW: Yes, it’s my first grandchild. My older daughter Katy is going to have a boy (Finn White was born on June 19, 2024 following this interview). So that’s pretty exciting and my other daughter Ginny is also really excited. She and her partner just bought a house down in the Kootenays, in Winlaw. She’s working her way through the Guides Association courses, so following in her dad’s footsteps.

SH: I hope you write a book because you’re so funny. Do you want to tell that ghost story you told at Whiskey and Words at the International Snow Science Workshop or is it too long? It’s a great story.

BW: I could tell the Readers Digest version if you want. (Tape 6:00)

This story was told to me several times when I was a kid so it might have stirred my interest in avalanches before I knew I wanted to be involved in the avalanche profession. So, the deal there was my grandfather Cliff and a couple of other guys including Cyril Paris who was a good friend of his, they had been involved in setting up a ski club at Mount Norquay. So that was the Banff Ski Runners, it was called. So, they built a cabin there, they got permission from Parks to build a cabin, and it was a good thing, skiing was catching on. So, they wanted to go further afield and the mountain guides, the Swiss guides in Lake Louise apparently said “Well take a look over there by the Red Deer Lakes area. It’s pretty nice over in that area, sort of on the east side of the valley from Lake Louise. There’s probably some good ski hills over there.” In the end they went there and got permission from Parks to build Skoki. It wasn’t that easy and originally, I think Parks didn’t think it was a good idea to build another cabin out in the backcountry of the park. In this day and age, you wouldn’t be able to do it. But they eventually got permission and they built Skoki Lodge in the fall of 1930 I think, which was a little lodge and they sold shares, and they made a new club because it was going to be farther afield than Banff and it was called “The Ski Club of the Canadian Rockies.” The Ski Club of the Canadian Rockies shares in the end became Skiing Louise, and that’s how come Skiing Louise still owns Skoki. The whole thing was started right at the start of the Depression so timing was bad, and people couldn’t buy shares and it looked like was it going to go belly-up.

My Great Uncle Pete and my Great Aunt Catharine agreed that they would take it on and run it I think in the winter of ‘32. Pete was also a keen skier and Catharine had some friends and associates from the east, because she was originally from Massachusetts. She sold this idea that everybody should come skiing up for some skiing at Skoki and they are running it as a commercial business and these people came and filled the lodge. Pete was the guide basically and one of the guys who came was Kit Paley, who was a mathematician from England, but he was at MIT. I don’t know if he was doing some kind of post-doctorate work, but anyways a very smart mathematician. He was also trying to get a badge through the British Ski Club where you had to climb so many peaks above 10,000’ on skis or something and you can imagine as a brilliant mathematician, he might have operated a bit differently than some of the other folks. He used to want to go off on his own and was told not to, but at any rate one afternoon off he went on his own and the avalanche conditions were not good. It was spring and he decided he was going to go up Fossil Mountain which he did, but he didn’t make it to the top before he triggered a big avalanche and he was killed in the avalanche. So, they went out searching for him that night and couldn’t find him and they regrouped the next day and had another search, and actually I think they found his ski pole attached to his hand sticking out of the debris and maybe a broken ski tip or something. So, there were some clues on the surface, but anyways they dug him out. So, he was really the first commercial client avalanche accident in western Canada I would guess.

Pete took it really hard; he had a death and got these people to come, Catharine’s friends, and it was a big deal. They skidded Paley out of there and part of the story is you have to read through the reports, but they had to explain why there was a rope burn on the corpse’s neck. But the toboggan had slid off the trail on a side hill and they had to hook onto him with a rope and pull him back up because apparently, he was a pretty big man. It ended Skoki as far as Pete and Catharine were concerned.

Anyways, at the same time there were a couple of other avalanche accidents. There were a couple of young guys called the Daem Brothers and they were going to ski from the railroad up to Lake Ohara and then to Field basically. They did this loop trip but, I don’t know if you know the terrain there, but it’s tiger country. Anyway, they didn’t get home and then a bunch of Swiss Guides and the Warden Service went looking for them and eventually they saw where their tracks disappeared into a whole bunch of avalanches in Duchesnay Pass. It wasn’t until spring that they managed to get into and dig out the Daem brothers who were both killed. So those two fatalities happened pretty close, within a year or two.

Then there was one more fatal avalanche accident and that was Herman Gadner. Now Herman Gadner was a guide and he had come to Temple to guide groups. A lot of the shares in the Ski Club of the Canadian Rockies were bought up, including Pete and Catharine’s shares, by a guy named Sir Norman Watson. Sir Norman was basically a remittance man from Britain but he had this vision of going to Canada and creating a whole bunch of alpine chalets with alpine cows grazing around them, so if you’ve ever read Rodney Touche’s book, it’s called “Brown Cow, Sacred Cow” about developing Lake Louise. But anyways one of the things he did do was developed Temple Lodge, the old Temple Lodge. That was part of the deal … it was a half day ski from the Lake Louise train station. So, my grandfather took on managing Temple Lodge. Cliff White, who still owned shares in the Ski Club of the Canadian Rockies. They previously had built a cabin which was called the Halfway cabin. That was about halfway between the Lake Louise railway station and Skoki.

So anyways, Herman Gadner was guiding out of the Temple Lodge, and this is in the early 40’s. I’m not sure if the war had started yet, but at any rate he took a group out up into Hidden Bowl and triggered an avalanche and was buried and killed so the deal was there was never enough ghosts for four to play poker or bridge but now with Gadner you had four ghosts. The Daem brothers weren’t even killed that close by but anyways there were these early avalanche deaths in the Rockies, and there’s now a bunch of ghost stories. I was told when I was a kid about how people would be skiing across the flats by Halfway Hut and see smoke coming out of the chimney, but then ski over there and there’s no tracks anywhere but there’s a fire still burning in the stove or stuff like that. So, the stories grew that these four ghosts inhabited the Halfway Hut, and they were the early avalanche deaths.

So, to finish it all up, Sir Norman built the Post Hotel so he had a place in Lake Louise and he had Temple Lodge and in the early ‘60s that became the development of ski hill at Lake Louise. Temple ski lodge got a lift then, Larch lift was the first one, and they got one up on the Ptarmigan side and eventually onto the Whitehorn side. Parks was involved in developing ski hills in those days too. It was Parks crews that were cutting the trails and all the rest of it, but that’s how Lake Louise came to be a ski hill.

SH: Wow, you know some great history. Would you recommend the Park Warden’s job to anyone today?

BW: I think you asked me, and I think there’s still jobs out there. You have to figure out what it is that interests you about working for Parks. I always use to have a saying that it doesn’t have to make sense. You have to learn to be able to turn off 30-40% of this noise that just seems like it’s trying to manage something inefficiently, but if you get out there and get on a trail, or go and climb a peak or you just go out there and sit and watch the sunrise, and realize what it is we’re protecting there and how special it really is. We are super privileged. If you can find something in your area of expertise that allows you to experience that, those things are priceless experiences.

SH: Is there anything I haven’t asked you that you want to bring up?

BW: I don’t know … we’ve been rambling all over the map.

Just back to thinking about what Willi used to say about the team. I would probably not be here today if it wasn’t for some of the very strong team members that helped us get things done. I could name a lot of them, but certainly the guides I worked with in my early years and some of the rescues that we pulled off together. You have to recognize that this thing was bigger than one person’s skill, or even a couple of people. We had to pull together to get things done. Doing that makes for good strong friendships, and makes you appreciate that it’s not all about you.

SH: Do you have a rescue that sticks in your brain, where you wake up and go …. or think about?

BW: I don’t think you ever forget all the faces of the people that didn’t make it. Some that are better than others, and you can brush off a little bit, and think “Well I don’t think that would happen to me.” But other times you just go, “There but for the grace of God go I.” That happened to me a bunch of times where people were in the wrong place or had bad luck.

This one, where we spent a long time searching for this fellow that went on a solo trip to Mount Columbia and he didn’t come back. I had arranged a few days of skiing in Rogers Pass. I don’t think I was working; I was just on a trip. So, we were up at Mount Fidelity and I get this call in the evening from Gerry. I was working in Jasper at the time. He says “Oh we’ve got this overdue. A guys gone off to solo Columbia on skis and he didn’t come back so you’re going to have to come back tomorrow.” So Okay, I cut the ski trip short because we have a search, but I’m at Rogers Pass on Mount Fidelity and I get up and it’s snowed like 70 centimeters overnight. The skidoo was totally buried. There’s a big storm. So, we were going to start at 7:00 so I better get up really early. So, I drive the skidoo from Fidelity on the road, all by myself, but I got to the highway without getting stuck which is better ski-dooing than I normally do. In fact, it’s not skidooing. I took a course not too long ago and the guy says, “Do you have any snowmobile experience?” I said, “Not really, but I’ve driven a lot of skidoos, but I’m not really a sledder.” He says, “You don’t drive a sled, you ride it.” I said, “I think that’s where my experience problem lies.”

At any rate now I get on the road and there’s a storm, and it’s really tough driving so somewhere around the Yoho gate there had been two semis in the fog, in the storm that head on. So it’s like 4 in the morning and I happen on this head on. But they’d avoided each other by each going to the opposite ditch and they smashed the cab off the passenger side of each of their trucks, and they are both without a scratch. These semis are in the road, so I go up and these guys are okay and I kind of hung around there for a little while, but there are no fatalities or even injuries and it’s not my gig so I got back in my truck and get to the Banff-Jasper highway and it’s tough driving, in the storm. So, I chain up all fours and climb up the big bend and finally get to Tangle Creek where we are going to meet. I can’t remember if we were going to meet at 7 or whenever but the road should have been closed, so I was talking to Dispatch about maybe you might want to close the road until the ploughs get here. But I get on the radio and say “Okay, I’m at Tangle now, where is everybody?” And I hear, “Oh it’s a little bit snowy in town right now, and we’re having a bit of trouble getting out of town.” We searched for that guy for quite a few days, and in the end, we found his car keys hidden on his car, and we got his car out of there, but we never found him. I think maybe last year, because the glaciers are retreating so much, they found his remains. He was like only a few hundred … well maybe a mile up from where he had started. He had just started up the glacier and fell into a crevasse or maybe he was on his way back. Maybe he summitted Columbia and fell in the crevasse before he got home. Maybe didn’t get very far but he melted out last year.

SH: Nice closure for somebody.

BW: We had another guy who was soloing on there and he had this giant pole that he’d attached to his arms and he was overdue. We searched, and searched and he didn’t show up. Then when we were flying, we saw him out on the glacier so we land next to him, and he says “No, I’m fine, I’m going to keep going”. And it’s like “No, you’re not, you’re getting in the helicopter”. “But what about my pole?” “No, it’s staying here.” So, we flew him home and it turned out he didn’t have a really good map and somehow he got over and down into the Alexandra (River). So, he’d been way over down near Castleguard Caves and finally figured out he was in the wrong place and had come back so that’s why he was two or three days overdue. But he had this long pole so he wouldn’t fall into a crevasse and how is that going to work if you’re parallel to the crevasse. Maybe he could turn it but I don’t know. It was probably better than nothing. I remember that guy up there.

SH: Good one.

BW: We never would have found him if he’d fallen in a crevasse. He wasn’t even in our search area. He had gone like 180 degrees the wrong way.

But if you ask me to wrap this up, I just want to say thanks to all the people that we managed to travel with, through so much good country. I was quoted once in some magazine where I said to this writer “Well they don’t build national parks in ugly places” and so the fact that it was a part of my career, I got to travel to so many of the nicest places in the nicest parks with so many great folks. That’s probably the way to wrap this up.

SH: Your photographs, because you are so talented with photos, are so stellar at capturing some of that, so I hope you give me some to include with this. Thanks so much for a very fun afternoon. (Tape 9:19)