SH: Did you have a favourite park?

Dan: They were each unique and special of course. I would think Banff. Being immersed in the mountain culture and being afforded the privilege of learning from highly skilled and competent wardens was special. While I think of those days through a nostalgic veil they were invigorating and rewarding. Little did I know that my only daughter Jessie would be born in the Mineral Springs Hospital years later in February 1983.

The range and scope of the work required diverse skill sets and knowledge. These were acquired through formal training sessions but more fundamentally, by working under the direction of experienced senior wardens. After a few weeks of townsite work I was assigned to work under Scott Ward in the Egypt Lake district. Scott is an excellent horseman and there began my experience riding and packing in the fabled historical district of Bill Peyto. There are many Egypt Lake stories but here are a notable few.

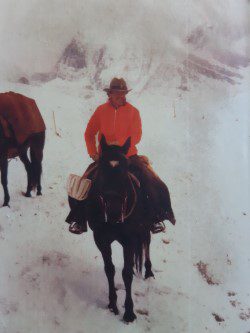

My first summer in the District was the “cowboy dude” theme; that being myself of course. Each morning we would check in with Banff dispatch over the single side band radio. One July morning I awoke to a landscape buried in snow and waited for dispatcher Moe Vroom’s daily call. She informed me that I was to come out as my mother was in hospital in Vancouver and the situation was urgent. The shortest quickest route out was over the Sunshine Meadows to the ski area where a stock truck would be waiting. I told her that the trail was obliterated by snow and the meadows had no visibility as they were encased in thick fog. She told me to saddle up my little mare named Leaf and that she would instinctively know the route out over the meadows. Oats and a comfortable stable she knew were awaiting. Sure enough the mare guided us to the truck. That evening I was in the hospital in Vancouver. From the 19th to the 20th century in half a day and one more lesson in the thousands to come.

That fall I was assigned to write the operational year end report for the District. Shortly after submitting it I was summoned to the Assistant Chief Park Warden’s office. There sat his eminence, Peter Whyte. With him was Keith Everts the leading avalanche control specialist in Banff who was responsible for the safety of the entire Sunshine ski area and the access road corridor. The report included some critical material and what I thought might be solution options. I so remember what I interpreted as a stern enquiry from Keith “Did you write this?” I knew the short career of a wannabe warden was over as I confessed. “Good” said Keith. He was looking to assemble a team to write the first resource management plan ever attempted by the Warden Service in Parks. I joined the group and Keith offered that should things work out I would be assigned a position on his avalanche control team the following winter.

So that winter of ’76 I wrote and also got to work avalanche control with John Wackerle at Mount Norquay. Growing up in the Austrian Alps during the war John spent those years on skis and was a member of the Austrian Olympic ski jumping team I believe. He was one of the best skiers in the Service. I had imagined myself as a ski god swooping beautiful “S’s” down the steep slopes of Norquay. Not that I knew how to ski. Once more I was summoned to an office, where John gave me a pair of skis equipped with wire bear trap bindings, leather boots and poles with leather baskets. And a stack of closure/danger signs to carry up and erect on the hill. No S turns, only Z turns, while carrying a loaded pack and struggling with an armload of signs. Rudimentary ski lessons followed by self taught survival techniques. It was heaven.

Meanwhile, Keith and John taught me the basics of backcountry ski touring. Up the hill on skinned skis and elevated heel bindings. Once on top, remove skins, lock in heels and downhill we go. More easily written than done.

Keith and I toured into the Egypt Lake cabin, back and forth, that winter to write the management plan while Tim Auger oversaw avalanche control at Sunshine. One early evening Keith and I had roasted a chicken in the wood stove. That crispy chicken and potatoes etc. sat on the stove top while we were enjoying a pre-dinner drink. The wood heat and the golden light of the lanterns contrasted with the -20 degree outside temperature. Suddenly we heard a faint but advancing scritch scritch noise followed by heavy stomping outside the door which then flew open. There stood a character from Lord of the Rings. Long hair and beard, festooned completely with snow on the army surplus wool clothing he was wearing. Taking in the scene and feeling the cabin warmth he exclaimed “Is this the Egypt Lake camp shelter?” Alas, we informed him that the shelter was across the meadow complete with a stove and wood supply. Decreasingly faint scritch scritch noise followed as he went to light a fire and wait for his friends who were to follow.

Dinner is over. Once more scritch, scritch stomp knock. “I can’t keep the fire going and the cabin is filled with smoke.” Keith told me to accompany him back. Donning all my gear away we went across the meadow to a shelter so completely filled with smoke I had to crawl through the 18 inches of clear air above the floor. Reaching the stove revealed that the poor guy, unfamiliar with wood stoves, had lit a rager in the oven.

Back to the cabin Keith had put together some food for the ski party and once more it was my turn to scritch scritch my skis back over to the shelter and back.

Second summer Egypt Lake after a winter of many adventures and experiences as a novice Park Warden. That summer I was teamed up briefly with Rick Kunelius. Our alternates to the district were Ed Carleton and Halle Flygare. Ed was a WWII veteran and a stickler for organization and order amongst the young ranks. He and Halle were excellent naturalists, and both possessed a broad depth and range of knowledge of the area’s natural resources. The camp shelter was located across the creek and meadow from the patrol cabin. It was a wooden structure with multi paned windows about to undergo an unwarranted remodel. Rather than making campers travel some distance for water Rick and I were assigned the task of digging both a ditch and small collecting area to and in front of the shelter from a nearby water source. Rick was an inventive and creative fellow. We were required to have blasting certificates for avalanche control and therefore access to explosives. Rick’s idea was to run prima cord and small pieces of plastic explosives along the planned ditch route ending in a ring of explosives intended to form a small pond immediately in front of the shelter. No pick and shovel, no sweat nor toil, no problem. Kaboom! Instant ditch, instant pond, instant smile followed by an “Oh crap” look. There sat the shelter covered in mud and windowless. Carleton and Flygarre just days away from shift change. Cleaning the shelter, repairing windows and painting required much more sweat and toil than pick and shovel. As for no problem? Sure would have been for Ed and Halle and because mud flows downhill for the two inventive Egypt Lake lads.

On my third summer in Banff I was assigned to the Cascade District under the direction of John Wackerle. John walked with a slight limp as years earlier he’d been thrown from his horse. His foot had slipped through the stirrup and he was dragged by the startled horse for some distance. By then the knee was permanently damaged. In spite of this he maintained his remarkable ability to ski.

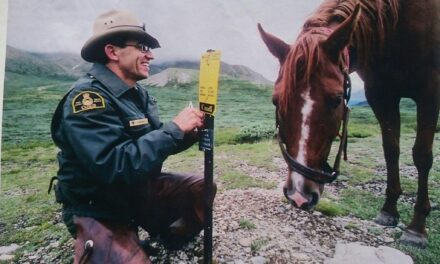

This area was occupied by a number of permanent seasonal outfitter’s camps. Food, garbage and grain storage was always a challenge in an area inhabited by grizzlies. We regularly visited the camps to monitor their management of bear attractants. It was a favourable working relationship as each camp earnestly worked to reduce conflict. There was however a footprint of soil and vegetation compaction left each year. I proposed a monitoring plan whereby we would take aerial flights and photographs at two altitudes over each camp at season’s end. The concept was to record macro changes to the landscape and to provide material to direct further in-depth field analysis. Such data could assist outfitters in reducing their environmental footprint through strategic operational changes.

Throughout that summer I fished Lake Minnewanka regularly. The lake trout were the best eating fish even compared to fresh Spring salmon. It occurred to me that some information in regard to the population dynamics of these fish was necessary in order to better manage stocks and angling activity. I set up gill nets in the spawning areas of the lake. The scree beds, characterized by large boulders, were prime spawning habitat. The fish heads were packed on ice and sent to the University of Calgary for otolith analysis. These inner ear bones are akin to growth rings on trees. Fish can be both aged as well as their year by year annual growth established. Size and age are key indicators to establish data in order to evaluate population status and trends. This would allow for a more science based approach to angling limits and seasonality. The target was to re-examine the appropriateness of the historical annual fishing derby and current fishing regulations. I believe my little study was not entirely well received in some quarters. As a side note the fish that were netted were given to the kitchen at the Mineral Springs Hospital. Best hospital meals ever methinks.

As the summer progressed I was fortunate to be on a two week horse patrol in the Cascade with Earl Skjonsberg and his search dog Faro. Faro was known to be somewhat of a nipper. Once on an avalanche search exercise at Sunshine he ended up with ski pant remnants in his mouth, if you catch my drift. When in town Earl would often ask me to run a mile or two practice track for him and the dog to follow. Earl’s instructions were always to sit at the base of a tree motionless at the trail’s end. Pharaoh, off leash and way ahead of Earl and his commands always arrived first. He’d approach and sniff my face. In bloody terror with sweat streaming down my forehead I would try and suppress any indication that I was even breathing until Earl would arrive on scene. There he’d call the dog off with his oft repeated command “Phooey that Faro”. Whereupon Earl would role up a cowboy smoke for the walk back. The dog and I always looked askance at each other.

As we rode along the Snake River on a beautiful August, perhaps September, morning the rescue helicopter, piloted by the famous Jim Davies, suddenly appeared low on the horizon. Landing alongside the river it was to ferry Earl and Faro to Marble Canyon campsite to search for a missing two year old toddler. In a flash there I was alone back to the 1800’s.

Earl was a very experienced horseman and packer. His lessons on packing remain with me today. On this particular trip he was breaking in a new colt. I was riding a big horse named Gunnar who was at times ill tempered. The third horse carried the loaded pack saddle. We were on our way to Windy cabin, another 8 miles down the trail. Johnny Nylund was Banff’s barn boss at the time. He was brilliant both in the saddle and with a lariat. Johnny, Scott Ward, Bill Vroom and Earl all had input into trying to make an urban cowboy into the real deal. Johnny’s directions were always to return the horses well fed, well groomed and without sores. We could be battered and bloody but NO INJURED HORSES. Tough and strong Johnny was always ready to make one atone for abusing a horse. Well ,on Johnny’s advice he determined that I was ready to ride with spurs. So there I was. Alone. Crappy Gunnar, beautiful but skittish colt, old pack horse and me adorned with spurs. I took it into my head to mount the colt and tail tie Gunnar behind. It was going so well for about 80 yards down the trail when suddenly a grizzly reared up in the willow alongside. The colt spun around, I caught a spur and the rodeo ensued. I was not coming off that horse. Next Gunnar and the packhorse disconnected and all four of us were racing at full speed, out of control, towards Windy cabin. Upon arrival, the packhorse had shed the pack boxes, Gunnar was in a lather, the colt and I remained attached, and the packhorse had suffered a small open gash. Johnny’s warning echoed like a doomsday bell in my empty head. The next few days were spent treating the small gash, reassembling broken pack boxes and grooming the horses. Upon my not so triumphant return to the corrals there stood Johnny Nylund. With only a cursory glance at the horses he said, “You had a wreck eh?” I knew after a drink or two I’d be forced to account.

Meanwhile at the Marble Canyon search site Earl and Faro searched for the lost tyke. This isn’t my story and I recount only what I was told. Apparently after what I believe was an exhaustive two day search the little guy showed up beside the highway a ways away from the campsite. Unharmed and still in diapers I think.

Marble Canyon also stands as the trailhead up a very steep valley to the Stanley Glacier. Later that winter, long after the campsite had closed for the season, a group had ski toured up this valley to its end. There they were hit by an avalanche with fatalities resulting. Utilizing the Marble Canyon Warden Station as a base of operations we helicoptered into the accident site to further our search. Our skis accompanied us and as the day ended the clouds closed in requiring us to ski miles out by headlamp. We could hear the avalanches rumbling in the distance. All that was visible was a crew of fire flies bobbing through the trees. The adventure was exhilarating all tempered by the sadness of a ski trip gone wrong. Little did I know then how important Marble Canyon would become to my warden career.

That fall after the rodeo. Keith had honoured his promise and I was part of the avalanche control team at Sunshine. At that time the Canadian military had developed a system to remotely detonate explosive devices. Keith was responsible not only for the ski area but also for the access road safety as well. The magnitude of avalanches are best reduced by creating controlled releases throughout the winter. Storm episodes, when the trigger zones are loading, are the optimal time to apply explosives. Storms at night precluded control. To allow for explosives control at night Keith had developed a system where 15lb bombs could be affixed high up in the trigger zones in the fall then detonated during winter storms. Each bomb had a cap fuse assembly wired to a high altitude radio signal receiving device. These detonation devices could be triggered with 1.5 volts. Each bomb had a unique code sequence which was sent by the controller to the mountain top during storm. Installing and wiring in six fifteen bombs per trigger site was undertaken in September. Being chosen to be part of this small team was an honour. No mistakes were tolerated. All circuits had to be closed as 1.5 volts could be generated by static electricity in this dry, high altitude. An open circuit would have been disastrous. Clear heads and focus were demanded of each crew member.

Ironically The Mineral Springs Hospital was again to factor into my early Banff experience and apprenticeship. I was working one September evening as duty warden in the townsite. There had been a mountain climbing fatality and Lance Cooper and Tim Auger recovered the climber’s remains and transported them via helicopter to the warden compound. Lance directed me to then deliver the body to the Mineral Springs where I was to assist in removing the remains from the Bauman Bag and to subsequently scrub the bag clean. Upon arrival at the hospital, I was met by two beautiful young nurses. With the Stetson on my head and an unearned swagger I helped move the enclosed bag to a gurney. We were to open up the bag in the basement morgue. While in the descending elevator I felt my swagger shrink and a nervousness overtake me. Time to drop the facade and admit to the nurses that I had never seen a dead human much less touched one. Furthermore, I wasn’t sure if I was up to the task before us. They nodded to each other and were kindly reassuring in a motherly sort of way. Not the way you want young women to perceive you. That was a dreadful initiation and foreshadowing into a world of numerous fatalities to come in my warden career. I was left saddened and numbed while driving on patrol in the darkness for the remainder of the evening. I was trying to reconcile the immense beauty of the mountains against the dangers residing there. It began to sink in that the job was not a role but a responsibility where team members entrusted their safety to each other. I hoped I would be up to the task.

My encounters with the hospital grew from the first donations of lake trout to those more serious in nature involving medical staff but culminating in the birth of my daughter of course. Nostalgia being what it is and being in my 20’s it is hard to beat Banff. I made good friends in the community, the work was enormously satisfying, and I pursued mountain activities with a passion.

SH: Are there other notable stories?

Dan: The Whiskey Creek bear maulings were challenging and terrifying. Much has been written about the event. The area, located on the edge of Banff, is characterized by heavy willow thickets, marshes and small ponds. As the prolonged hunt went on wardens from other mountain parks were brought in to provide perimeter monitoring and control. No one goes in and no bear exits undetected. What was terrifying was that Banff wardens were assigned the daily task of entering the closure area to stalk the animal. There I was, in my mid 20’s, shotgun in hand, pushing through heavy brush with barely 10 feet of visibility around with little reaction time to shoot a large grizzly that had already mauled two men. That was terrifying. I was teamed with John Wackerle. After our daily stalking we would take up a perimeter station hoping to catch a glimpse of the animal. One morning we heard radio chatter about an elk calf that had been killed on the highway. John instructed me to retrieve the calf and bring it back to set up a bait. While John stood guard some yards away, I was to tie the remains to a log in hopes of luring the bear.

Now at that time most backcountry wardens discreetly packed handguns. This was a necessity as the long gun was inconveniently out of quick reach when heli relocating grizzlies. So here I was late in the day setting the bait, rifle set aside, but my 357-magnum hidden in my armpit under my jacket. Suddenly I heard movement immediately behind me. With nerves already on alert and sensing that it was our prey I spun around pistol in hand ready to empty the magazine into the animal. There stood a young fellow dressed in white sporting a blond beard and long flowing hair. For an ironic second I thought perhaps the bear had killed me and I was about to shake hands with Jesus. It turned out to be a cook taking a shortcut to work, who had somehow evaded John, and I almost accidentally shot him. We charged him for entering a closed area and I think the judge fined him $500. Later that night after an 18 hour shift I saw a large bear sauntering toward our bait in the dark. We were poised to snap on our spotlight. John had assigned me to take the shot while he managed the light. Just at that moment a television crew some distance behind made a startling noise and the animal wheeled around disappearing into the dark. John either had more confidence in me than I deserved, or he outwitted me knowing how difficult an open site shot in the dark would be. Either way it was undoubtedly my good fortune not to have taken the opportunistic shot. I would have forever been labelled as the dumbass junior warden who had bungling bad aim and not the legendary bear hunter. The bear was caught in a snare later that night to be dispatched by the morning crew. I was at the warden compound later that morning to land a 780 pound black grizzly onto a flatbed trailer located behind a chain link fence.

Ironically some years later my sister called to tell me my picture was in the National Enquirer. Sure enough there I was uncabling the bear onto the trailer. Above the photo it read “Killer Bear Besieges Mountain Town”. Much better than “Junior Warden Bungles Shot in the Dark” I think.

Very well related and composed Dan. It’s obvious you made a significant contribution to the Warden Service as it once was. Having spent over 35 years in the Service myself, I can relate somewhat toyour glimpses into the early Service histronics, great work accomplished, dedication and sacrifices by so many. You have enveloped many of those attributes in your recital. Thanks and good luck in your retirement.