SH: What was she doing …. Interpreter?

Dave: Yes, she was an interpretive specialist for Historic Sites.

Again, Cornwall wasn’t a desirable location back then, so I spent the next five years trying to move out of Cornwall. Finally in 1985 I got an assignment opportunity to help coordinate National Parks Centennial events at Harbourfront in Toronto and that was a big deal. That went extremely well; we had Parks and Sites from all across the country and that allowed me to get an operational assignment as the Superintendent at Woodside National Historic Site in Kitchener.

But in the meantime, as a senior planner in Parks Canada, we were pulling together a whole lot of plans, updating them and pulling them together, to get them approved. We had ten plans approved in just over a year, a year and a half, because previously there was an issue in trying to finalize these plans. Nobody really wanted to finalize a plan because then there were commitments. That exposed me to national historic sites, national prehistoric sites, national parks and heritage canals and waterways. So, I got to work on every kind of park in the organization at that time. My one regret is I never did end up working with a national marine park and I would have loved to have done that.

From Woodside, I moved to Operations on the Trent Severn Waterway, and that was a terrific experience. But the job, which I always saw through the lens of science and ecology, turned out to be all about staff relations. Terrible staff relations …. everybody in that area, on the Central Area of the Trent Severn, were former unionized factory workers, from factories that closed in Peterborough. There were disagreements about everything imaginable, so it was a very challenging workplace.

Eventually I managed to get through an interview with Prairie Region and moved to Prince Albert National Park as the Superintendent. I was able to use a lot of my experience to apply inter-disciplinary approaches to everything really, not just science and ecology, but integrating that with visitor use, interpretation and everything else.

In those days the thinking in national parks was evolving. In the earlier days there was a fortress mentality in national parks. We only looked after things inside the park boundaries, and everything outside the parks wasn’t our business.

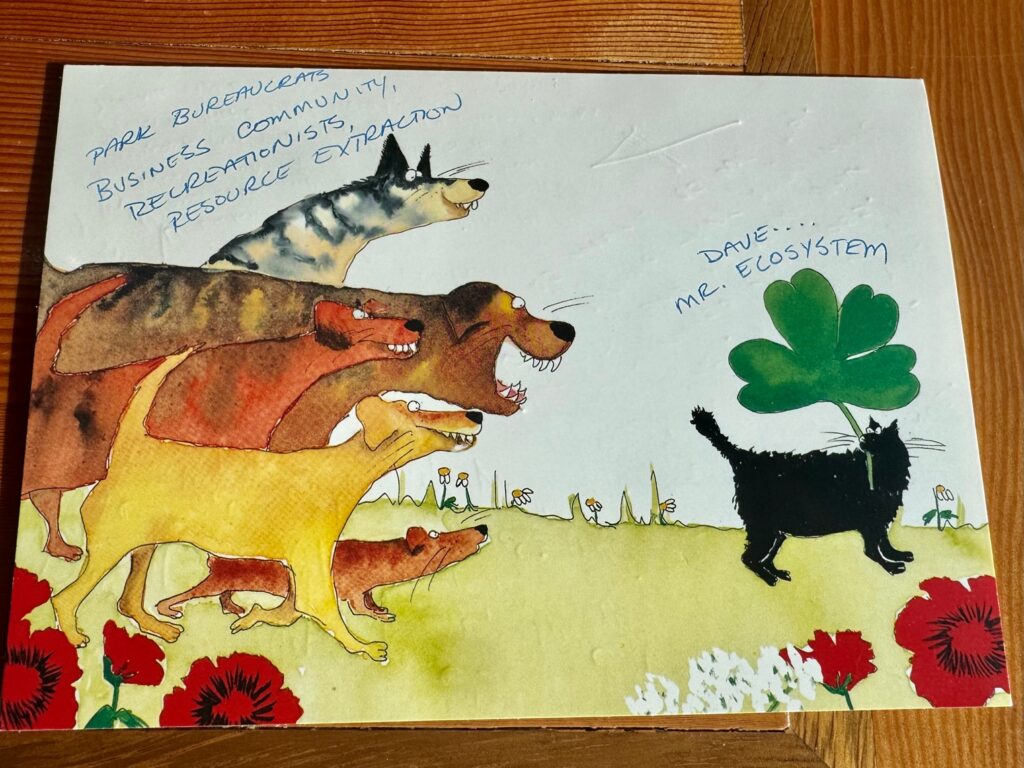

When I moved to Prince Albert, Paul Galbraith was the Chief Park Warden there, and he got us involved with the Prince Albert Model Forest. The model forest was exactly what we needed to do. We got to think outside the boundaries of national parks. We had a lot of questions from the public about “what is a national park like you doing in a model forest with logging companies” and what they envisioned was, “Oh you guys are just going to log the whole national park”. We saw it as an opportunity to do far better ecological integrity and ecosystem protection by increasing the influence of the park outside the park boundaries.

But a funny story regarding that is when I arrived Paul held our position on the Board of Directors. I took up that position and he introduced me to the Board, but failed to mention that my first responsibility would be to say a prayer. I’m not a religious guy, so this was a surprise! Four of the seven members on the Board were First Nations people. It was a bit of an awkward moment, but they all appreciated the fact that this was unexpected.

One of the Chiefs decided that he could handle that responsibility. It was an awkward moment and Paul and I still laugh about it. We did some fun and interesting things, ecologically, with the model forest …. an excellent model.

I arrived in Prince Albert National Park in 1992. The thinking in Parks Canada was to try to make a more efficient business-like model for running the parks. There were a lot of things going on at the national level. I was invited to participate in things like the national revenue steering committee and the national human resource framework working group, and the recourse working group, and the national business plan. So even though I was in Prince Albert, I was on the road so much of the time, it was a very difficult time for us as a family.

SH: You had a couple of kids by now?

Dave: We had three kids, and Mary was working full time. Mary was working as an Environmental Site Manager for BOREAS, the boreal ecosystem atmospheric study under NASA, so it was a very difficult time with me being away weeks at a time, almost every month. Fortunately, the staff and the environment in Waskesiu was very supportive of families.

SH: What year would this have been?

Dave: This would have been 1992, 93 and 94. Some of those things resulted in very successful improvements to Parks Canada. I had to work with one of our Union adversaries on the Trent Severn Waterway when he became the Union President a little later. He was quite a difficult guy to work with on the Waterway. He was on the maintenance crew and walked around with a hip pocket full of grievance forms. They were just grieving anything they could think of. Not for anything I was doing but for the broader park program. They just wanted to create problems. So, he became the designated Union participant, and we actually worked really well together and sorted out the new workplace recourse system for Parks Canada that led to significant efficiencies. (Tape 19:59)

When I was offered the job at Prince Albert, Mary and I travelled to Waskesiu to determine if we would move there and I remember it was December 21st just before Christmas. It was really dark with a storm coming in. There were only 40 people living in the little Waskesiu townsite, and half a dozen of them would come out to a movie night. On the night we arrived it happened to be a Tuesday night, and the only place that was open in town was this small hotel and restaurant. Mary and I had dinner, and it turned out it was movie night, and the movie was “Silence of the Lambs”. We thought “What are we getting ourselves into?”

We had been told that Prince Albert was a very unionized park, difficult and militant. I met with some of the people, and I thought maybe we can make this work. I certainly had a lot of experience with staff relations, so we accepted the job. I moved to Waskesiu in April and Mary moved out with the kids in July. So, it was a long time for Mary on her own, working full time with the kids. It was a tremendous challenge for her. The kids were young in those days. But we got there, and I had an excellent relationship with not just the Union President but all the staff. There were a number of union grievances, that were pulled back and we were able to develop a very harmonious relationship there, to the point where we didn’t have any grievances the whole time we were there.

I loved Prince Albert National Park. The staff were fantastic, they were dedicated hard working people, wonderful people. The townsite was full of Saskatchewan elite, the political elite, the business elite in Saskatchewan. I worked very well with them too. Overall, they were a great group of people, and it was certainly my favourite place to work.

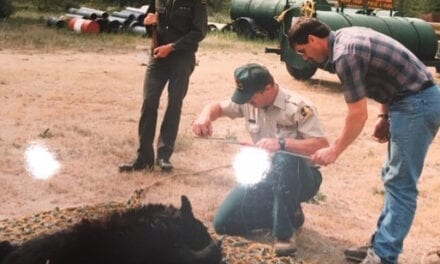

We worked on fisheries rehabilitation, removing bison from a fenced enclosure, as there was a free roaming herd of bison in the south-west part of the park, and completed a new management plan for the park.

In late 1994, after the merger of Parks Canada with Canadian Heritage, they decided they could run parks better on a provincial or regional basis, using directors for Saskatchewan, and Manitoba. So, they were eliminating the positions of Superintendent. I saw this coming, so I applied for the Chief Operating Officer position for the Hot Springs Enterprise Unit, another experiment under the national business plan.

Because I had a background in the private sector beforehand … in grad school I had my own business and worked in private consulting, so I was able to leverage that experience to demonstrate that I had the capacity to run a public sector enterprise, and I moved to Canmore.

SH: Had you been to the mountains before?

Dave: I had been through the mountains. In 1978 I gave a paper on planning and managing national parks at a remote sensing symposium in Victoria. This was just after Mary and I got together. After the conference we had traveled all through the mountain parks and that was my first time in the mountains.

SH: So, you came applied for this job and came to Canmore and that was about when I met you.

Dave: Yes, that would have been 1995. Again, I came here three months before Mary moved out. She was working full time, had three kids she was looking out for in Prince Albert National Park in the winter, when there are no other kids nearby so that was another huge challenge for Mary and her support was amazing…until she started reading my credit card statement.

SH: Okay (laughs)

Dave: I phoned her one night and asked if she thought I should get full shocks on a mountain bike I’m buying, and that was when I heard a piece of her mind. She said, “You’ve bought skis, boots and poles, you’ve bought cross country skis, boots and poles, you have bought a flyfishing rod, you have a personal trainer and now you’re buying a mountain bike? I don’t think you should get shocks!” So, I didn’t get the shocks. She was shocked enough.

SH: That’s funny.

Dave: That was a bad night. Anyway, she joined me in Canmore in July. The Hot Springs Enterprise Unit was a real interesting challenge. Running a public sector enterprise …the message that people got was, “Well we are actually a private sector thing now and we can write off this and that.” So, the next thing you know expenses were right out of control. The first guy moved on and I completely changed the program. The Hot Springs Enterprise for the three years that I was there was very successful and it continued to be a good working model. We were able to work as a private sector operation on a full cost recovery basis, including renewing all the hot springs with substantial capital investments without public funds. We centered our operations on the visitor, making the whole experience better for visitors. We reduced the cost to government. There were private sector expectations, with all the baggage of the public sector.

It was great and it was fun, but it wasn’t why I joined national parks.

SH: Why did they decide to abandon that model?

Dave: I don’t think they completely abandoned the model, but I don’t know what changes have been made.

SH: So, you decided to stop doing that job and ….

Dave: Then I was offered the opportunity to come to Banff National Park as Manager of the Ecosystem Secretariat, which was a new organizational model. It was just the kind of thing that suited me. It was inter-disciplinary and frankly it was so much fun. It was a great model and that’s when I really started to work with the Wardens in the mountain parks. I worked with a former warden, Sean Meggs, who was the manager at the Upper Hot Springs for a while and then he moved to marketing. Shawna Wilkinson was a lifeguard at the time and she moved to the Warden Service. I crossed paths and worked with many wardens including one from Point Pelee when I was doing my thesis who was a pilot. I rented his plane to fly over the park to do aerial photography and remote sensing. I had many interactions with wardens throughout the time I was doing this.

SH: So, your job started after the Bow Valley Study?

Dave: Yes, it started just as the 1997 Banff National Park management plan was approved.

SH: It was a recommendation from the Bow Valley Study?

Dave: I’m not sure if that’s where the model came from. There was some overlap, as the Park Management Plan for Banff was based on the Bow Valley Study. Jillian wrote the 1997 Banff National Park Management Plan and it was an excellent plan. It really gave us fuel to start dealing with the educational and scientific issues, the ecological and resource management issues that we had to deal with in the park. (Tape 10:57)

As the Ecosystem Secretariat Manager, it certainly wasn’t without challenges. There were massive challenges really. One of the park managers referred to the Bow Valley Study as a door stop, when it was one of the most excellent pieces of scientific information we had by far in the program. It was top drawer.

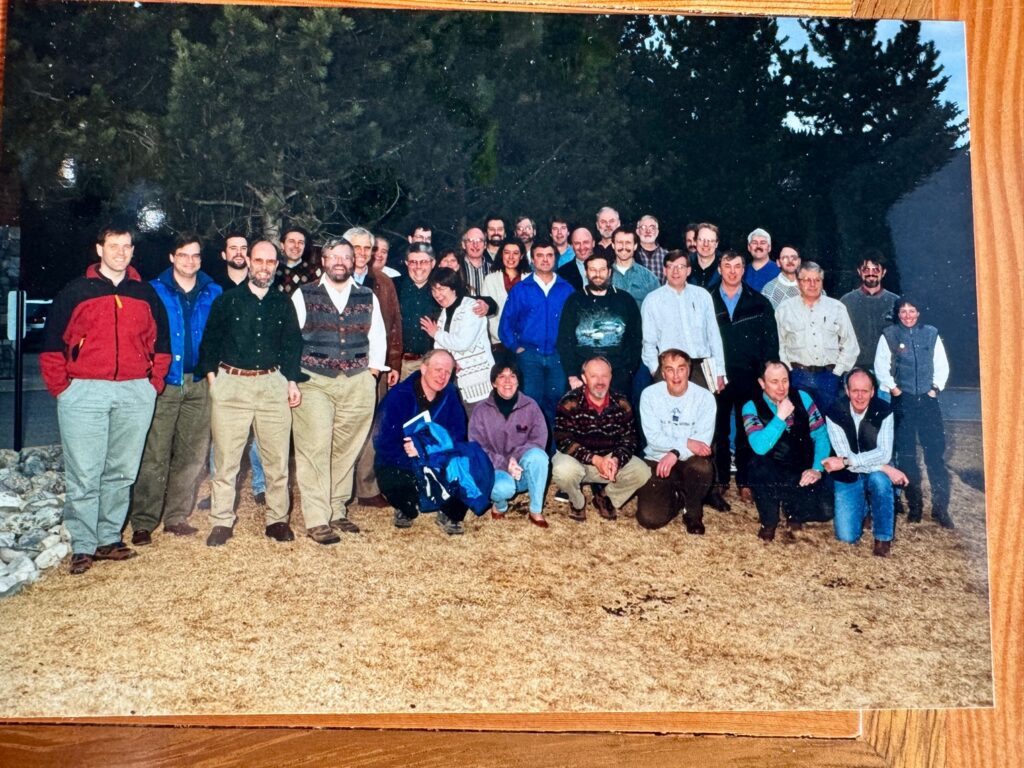

Then I got to work with people like Cliff White, Tom Hurd, Ian Pengelly, Charlie Pacas and Paul Galbraith because we worked closely with the Warden Offices across the Mountain National Parks. Heather Dempsey and Darrell Zell were there; Heather was almost the conscience of the organization, really the Warden Service was the conscience of the organization and Heather exemplified that; wonderful to work with her. I also got to work with other women in the Warden Office …. Julie Timmins, Diane Volkers, Helene Galt, Christine Aikens. It was terrific.

I’m going to roll back a bit to PA. While I was in Prince Albert, Paul Galbraith was the Chief Park Warden. Because Paul was on his way to Jasper, we hired Greg Fenton for the position of Chief Park Warden. Greg was a saint of a guy, an excellent, smart guy … I really enjoyed working with Greg and the person that I actually followed to Prince Albert was Doug Hodgins. Doug had moved on to be the Executive Director of the Bow Valley Study. So, it was interesting because our paths continued to cross. I talked to Doug a lot when he was the Ecosystem Secretariat Manager for Jasper and when I was at the Ministry of the Environment, trying to get insights into how to compete for a job at Parks Canada. There were also great people at Prince Albert, people like Paul Tarleton and Jim Durnin. We had lots of other really good people there.

But back to Ecosystem Secretariat, I got to work with all of the Chief Park Wardens in the Mountain National Parks. Paul was clearly a leader, but they were all leaders; Bob Haney, Bill Dolan, Perry Jacobson … these guys were brilliant guys to work with so I was really happy to work with them.

Warden Service and Ecosystem Secretariat Manger’s Workshop, Jasper 1998

The work that we were able to do, the inter-disciplinary work really started to move things ahead for ecological integrity in the parks. Not without bringing along visitor services because visitor services was essential and educational opportunities that were brought forward by including science in decision-making was crucial. We were able to do some pretty excellent communications about science in the resource management decision making process of parks and Heather brought that forward magnificently as the Ecosystem Secretariat Communications Specialist.