But after about three days of this, there was a lot of frustration and Fred Dixon piped up at the back of the room at the morning meeting and said, “Are you serious about catching these buffalo?”. CWS staff looked at him quizzically and said, “Well ya.” and Fred says, “If you want them caught I can catch them for you”. So they’d tried everything else so said, “Okay.” So, Fred called Bill Walburger in Elk Island and said, “Bring out a portable trap, an elk trap”. It was just a net trap and a door. Fred and I, that afternoon, we found out where the buffalo were in this meadow with a grove of aspen at the edge of it. We contacted the landowner and cut the centre of the aspen out. Next day we showed up with the net trap and strung the net trap up and rigged the door up. I’d gone out and got a couple of fresh cut alfalfa hay bales and in the morning, I drove the truck and Fred sat on the tailgate calling the buffalo and feeding flakes of hay and we had the whole line of twenty buffalo lined up behind the pickup truck and drove in through the trap. Walburger was hiding in the bush with a rope and when I came out of the truck he slammed the door to the trap and we had twenty buffalo. So that was an old boy with about a grade 8 education versus somebody with a PhD.

SH: Didn’t one of those bison end up staying in Jasper? (Tape 26:26)

There was one male and he split off from the group, had a collar on, and he went down to a place called the mushroom patch. And he lived there for about six years. He was seen every once in a while. I went looking for him a few times. Found him a few times. It was a little spooky looking for him because there were very dense willows where he was living. You’d go in there and there was buffalo crap everywhere. You’d stop and listen, and you’d get a radio signal but you could only see twenty feet. And you’d think, “where is he”. You’d hear him crashing around if you got too close and you’d think, “Is that crashing coming this way or going the other way?” So it was a little spooky looking for him but I saw him a few times in there. And then I moved on job wise. Actually, I left Jasper and went to Lake Louise, and he was still in there a couple of years after that. (End of Section 2: Tape 27:29)

Part 3 – 10:55 am

Dave: Just to finish up in Jasper, I got to work in the Smokey District, I got to spend the summer in Willow Creek with the bison, spent a season in the Tonquin, and spent three winters in avalanche control in Marmot.

SH: So how many years were you in Jasper?

Dave: Six summers and I ended up on my first winter there, I ski patrolled at Marmot when Hans Schwartz was the head of the ski patrol. Working for Hans was fun, interesting guy, lots of climbing stories from around there. So that was good. By now I was really hooked on the job because I was getting paid to ride horses in summer and ski in winter. I figured that was pretty good. I met a lot of interesting people while I was there. Brian Wallace was great as a mentor and set the tone for what the Warden Service was all about. Al Stendie, he was an interesting guy. I’ve got to tell a Stendie story.

Dave: Al liked his cigarettes; I forget what brand they were, but they were menthol. A lot of us smoked in those days, I did too. But Al …. he consumed cigarettes. Anyways, we were on a climbing school one year and we climbed Mount Columbia. And Al was with us. Old Al, we called him old Al, but at the time he was probably thirty, and the rest of us were 28. Anyway, he made it to the top of Columbia and I have a mental image of him sitting on his pack, smoking one of his menthol cigarettes. He was just about as grey as the clouds. And heart barely ticking while he was smoking that cigarette. But he made it to the top, and I gave him a lot of credit for that. He wasn’t the fittest guy, and the cigarettes didn’t help, but made it up there on sheer determination. I think because rest of us figured he wasn’t going to make it, so just to spite us, he did. That was led by Pfisterer, Jasper was my introduction to Willi ….. There’s a hundred Willi stories. He was larger than life to say the least. (Tape 03:21)

Climbing school. Photo contributed by T. Damm.

Another interesting guy in Jasper was Toni Klettl. I really liked Toni. Obviously German and Austrian descent, hard to understand sometimes, but I liked him, a nice guy.

Anyways after that I got offered a full-time job in Lake Louise. So, fall of 1982 I went to Lake Louise, and was introduced to a whole different group of people, and a different way of doing things, different jobs. I started working in avalanche control at Lake Louise, for a total of about five or six years I guess. I was working for Clair Israelson, at Temple Research. I met a lot of wardens there that I ended up working with for the rest of my career in different capacities. That was a good learning experience, working in avalanche control; good hands on experience. I learned a lot about how to stay alive in the mountains. You got a chance to get right into it and test what was stable and wasn’t stable. You could find out first hand, you didn’t have to guess or wonder. You could actually find out. So, I learned a lot quickly there. Working for Clair was interesting. He’s a dynamic individual to say the least. He had great abilities, he was strong physically, decisive, a lot of natural ability and a supreme confidence in himself. He was the kind of guy in a tough situation that people just automatically followed. He had real leadership qualities in that respect. He could be a horrible to work for at times, because he was impatient, but when the chips were down, and something had to get done and it involved risks or hazard, Clair was the guy you wanted with you. With him you’d probably be alright. I had that feeling on a number occasions, and situations we were in, where Clair was on the front end of it.

SH: Do you want to talk about one of those now? (Tape 06:32)

Dave: I don’t know which ones stick out.

SH: My favourite with you was the Ferris one. Do you remember looking for Ferris? But you don’t have to talk about that. You can talk about whatever you want.

Dave: No, I’ll talk about the Ferris one. The guy went hiking solo up to Bow Hut, or that’s where he said he was going, but he went up to the left behind Bow Peak and ended up on the Glacier. His hiking partner who didn’t go with him that weekend, said he’d never venture onto the ice by himself. It was something he’d never do. Well he did. Anyway, looking for this fellow, we put people out on the ridge tops and all over the place, looking for some sign and spent all day doing it. Late in the afternoon the helicopter dropped me off on the ridge of Bow Peak. Diane Volkers was on the same ridge, about half a mile away. Anyway, when I was up there it was quiet but I heard a whistle, and thought that’s a marmot. To the point where I even called Diane on the radio and said, “Do you hear that marmot whistling?” She said, “Ya, I heard it too”. Anyways, we didn’t think any more of it; just thought that’s what it was. Anyways we walked and hiked and met at the rendezvous point, and got our helicopter ride back to Num Ti Jah Lodge where the base of operations was. The weather was getting black to the west, with a severe storm rolling in. Tim Auger said “We’ve got half an hour left at the most. I’m just going to fly up there and have one more look.” So Tim went up and was sitting in the front seat and he opened up the door so he could look straight down. They flew over the glacier on the back side of Bow Peak, and just as he flew over a crevasse he saw movement. And about thirty feet down the crevasse there was Ferris standing on the ledge waving at him. Tim called up that they found him, and they hurriedly put a group together, flew up there and yarded him out the crevasse. They came back, and he’d been in there a day and a half by then, standing on this ledge about a foot wide. He actually had taken pictures with his little instamatic camera, of the belly of the helicopter, as it flew over this crevasse from previous searches earlier in the day. So if he had never been found, when he was finally spit out of the glacier 300 years from now, if they developed the film, they would have seen pictures of ALM (helicopter).

SH: I just remember that one because Clair told me at one point, because I was working at the staging area, and you were a strong personality there, and it was really getting cold and ugly. Clair was trying to give the group his last pep talk and you said, “Ferris is dead Clair.” Funny.

SH: What were some of your main responsibilities over the years (Tape 10:42)

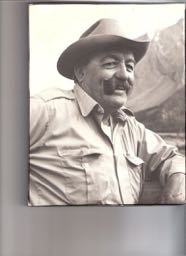

Dave on a training school. Photo contributed by T. Damm.

Dave: Lake Louise was more of the same that I was introduced to in Jasper. More skiing in the winter and backcountry riding in the summer. That was great. Every once in a while, generally there was a two-year rotation in the generalist warden group and you’d do something for a couple of years, and then everybody would jump up and change seats. I was lucky, I got backcountry for a couple of summers. Then it was frontcountry stuff which was campground patrols, which wasn’t as good but that also put you front and centre in Lake Louise, anytime there was any rescue work. In those days everybody got involved so I got exposed to a lot of that kind of stuff.

Chasing grizzlies around Lake Louise, there’s always no shortage of them. Rescue work, that was interesting. Ron Leblanc was working there, he was a seasonal who’d come from Waterton. We had roadside grizzlies …. bear jams. Grizzly bear jams on the Banff Jasper were a real problem, they still are a problem and as long as there’s tourists and bears there will be a problem. That summer it was a problem. There was a growing awareness in the Warden Service about preservation. The whole business of if you have a problem bear you just shoot it, that was going away. We were becoming more informed, more educated, more aware. Ron had taken wildlife management at the University of Missoula. We had this female grizzly with a couple of cubs on the Banff-Jasper (Highway) that was frequenting the road. Ron was the one who drove that and said, “We’ve got to do something here or that bear is going to end up dead”. So he had a friend in Montana who had a gun that he had made that shot rubber bullets as a deterrent. Ron was able to get the gun up from Montana and he set up a program where we worked 24 hours a day shooting that bear with rubber bullets anytime she came close to the road. That bear was named Blondie and that kept that bear off the road, she stayed near the road but stayed away from it during the day. She ended up having three sets of cubs that I know of. She was eventually killed but she had three sets of cubs up there successfully. That was Ron’s idea to begin with and it worked out great. This whole conditioning of bears and how you deal with road jams evolved from that. So that was interesting to work on. (Tape 14:18)

SH: I didn’t know any of that. Interesting.

Dave: I spent a season on environmental monitoring.

SH: At the ski hill?

Dave: No, different projects around, Chateau rebuilding, Baker Creek bungalows was rebuilding, Moraine Lake Lodge was rebuilt. So somebody had to go around and see what they were doing. Do the paperwork. It wasn’t one of my best jobs, but somebody had to do it.

Dave: I’ve got a Clair story in Lake Louise. When I went to Lake Louise there was no manager. Mike McKnight had been the manager, but he had just gotten a Chief Warden’s job in Georgian Bay, so he’d left. So when I showed up the GT 4’s were taking turns every 6 months or 3 months, or whatever it was, they were rotating the manager’s job around amongst themselves. Which seemed to be okay. But after about 6 to 7 months of this, Gaby Fortin arrived from Waterton as the new Chief in Banff. He hired a new manager for Lake Louise, John Steele. John came down from Jasper. I knew him up there. He was a smart guy, and there were some things he was good at but people management was not one of them. He was a strong individual, and gravitated to law enforcement. He would best be described as if the Warden Service needed a detective, John Steele would have been your man. As a people manager in a place like Lake Louise with a lot going on and a lot of strong willed dynamic people there to manage, it didn’t work very well.

Anyway, John instituted a new program there … Monday morning meetings. We were all going to sit around Monday morning and tell each other what we were up to for the week and what we’d done the previous week, and have this Monday morning meeting. Clair didn’t think Monday morning meetings were necessary. Anyways, we were all gathered in the office for this Monday morning meeting and the only one missing is Clair. Clair stayed in his office. Steele hollered for him to get out here. So Clair came up and sat down and you could tell he had other things on his mind, he wasn’t happy. He pulled out his pipe, filled his pipe and fired it up. A big cloud of smoke drifted up and set the smoke detector off. So, we’re all sitting there, Steele up front like a school teacher sitting on his desk, and this smoke alarm is going off. So nobody said anything or did anything and Clair just quietly got up, with the pipe clenched in his teeth, picked up this aluminum snow shovel that was behind the door and smashed this smoke detector off the ceiling with it. Bits of plastic flew everywhere. The rest of us just kind of leaned over so we weren’t hit by the debris. Clair put the shovel back in the corner, sat back down and relit his pipe as if nothing had happened. Nobody flinched or said anything and Steele was sitting there looking at us, and his eyes were as big as pie plates. I think that’s when it really hit him, “Holy Smokes, do I really want this job?” We didn’t have as many Monday morning meetings after that. (Tape 19:11)

SH: What did you like about being a warden? What didn’t you like about being a Warden?

Dave: What did I like? The best part, I think I mentioned already, is it doesn’t get any better than somebody paying you money to go skiing in the winter and riding horses in the summer. I got quite a few years of that combination in one year. We would go from riding the boundary on the Clearwater, and come off the trail on October 31, and the first week of November we were up at the ski hill getting ready for the ski season. And then you’d ski til mid-May, maybe get two weeks off and the first of June you were heading out to the Ya Ha Tinda to ride horses. So you’d do a little horse school and by the 15th of June you were on the trail. I did that for a number of years and that was great. That was the best time I think, when the Warden Service were all generalists and got to rotate around. You’d fall into things that you liked and agreed with you. That’s what I liked.

SH: So what didn’t you like about being a warden? (Tape 21:07)

Dave: In the early days, there wasn’t much I could complain about. Nobody really liked working night shifts in campgrounds telling drunks to shut up. That was a disagreeable part of the job. Some people liked to do that but I didn’t. In Lake Louise at first, we ran the ambulance service in those days, not only mountain climbing, missing people and hiking accidents fell under public safety, but road accidents fell into our job description as well. I didn’t like that part, nobody liked it I don’t think because you’d get that call late at night, whenever the phone rang if you were the duty warden, and you’d be roaring down the road not knowing what you were going to. Some of the things were pretty horrific. That kind of stuff no matter how stoic you try to be, it sticks with you. They were worse than the mountain climbing ones actually. Because the mountain climbing ones, people doing that, they knew what they were doing and if they got injured or killed, it’s still sad but they went into it with their eyes open. But stuff on the highway was just plain ugly. In the blink of an eye people were dead. It wasn’t very nice. (Tape 22:59)

SH: We’re talking about what Dave didn’t like about the Warden Service. Are we finished that one now Dave?

Dave: Well those were just work things. By now I’d been around for 8-10 years and you start to see some of the down side about working for a big bureaucracy like the Federal Government. Some things about any government organization, they’re cumbersome, awkward, stupid. I learned after a while that you either accepted that stuff and realized it was part of the big machine, and really not much you could do about it, or you could …. I had friends in the Warden Service who didn’t last. They couldn’t stand it, the bureaucracy and the arbitrary dumbness of a big bureaucratic machine like the government. They just couldn’t take it and they had to leave. They weren’t cut out for it. You had to come to some kind of reckoning with yourself, if the good outweighed the bad or it didn’t. For me the good far outweighed the bad, and I lived for the good moments.

SH: What are some of the more memorable events of your Warden Service career? Tape 04:37)

Dave: Memorable. Oh, skiing at Rogers Pass. Anybody who was a warden and got to do that will remember that as a highlight. I’ll tell a Cliff White story on a deep snow school. Two people stand out on those schools. We were skiing the Bostock headwall after a huge snowfall. The snow was waist deep. The Bostock headwall was one of the few pitches you could ski because it was steep enough. We were all tearing down that thing like a bunch of crazed banshees, and we get down off the headwall and we’re in the top end of Bostock Creek. Cliff White was out front. I’d stopped on a little knoll watching how guys were going to deal with the top end of this creek because it was about 30 feet deep and quite steep. Cliff came flying down and I don’t know if he needed glasses or what, probably glasses, but he’s not wearing any glasses in those days. Anyways, he’s just flying with abandon, like he usually does, with his hands up above his head, screaming and hollering. He goes off the bank of Bostock Creek and flies right across the creek and he sticks into the far bank and it was just like a Wiley Coyote cartoon. Spread eagled, stuck, his tips went straight in and he’s stuck on the far bank, spread right out, spread eagled. And he’s about 20 feet off the creek bottom. We all just stood there and roared with laughter.