We had some challenges out there. I know there were lots of folks who thought that the breeding program was a huge success, and without a doubt it was at the time. Financially, it was not workable in the long term. The cost of breeding and having veterinary capacity to give birth to colts and raise those colts, you pretty much had to raise whatever you got without too much culling. We had to move to more purchasing of colts, with Rick and the staff at the Ya Ha Tinda. They set up a purchasing program with trusted horse breeders with some great colts that we were able to get access to. We wanted colts that had no human interference whatsoever. Rick and the boys just wanted to start them right off before they were hardly handled at all. If a young horse wasn’t working out, we sold it. It was a pretty good program and ended up with some spectacular horses for the Warden Service and Resource Conservation. Most of the folks that got hired at that time didn’t have much horse experience and yet we were still doing significant backcountry work. The training program both for the horses and the people at the Ya Ha Tinda, and park barn boss staff put together was quite something. But things change, there’s a new manager out there now. Rick and Jean were there for 12 or 13 years and moved on, but it was a big part of my role in Banff, that’s for sure. A wonderful part. I’m kind of jumping all over the place there.

SH: Let’s go back to stories. Can I make you tell one? It’s a funny one that shows your charm. I want you tell the story about your dog at Palliser.

Ian: Laughs. Oh that’s going back to the mid 80’s. Terry Skjonsberg and I had gone into Palliser cabin late in the year, late in the fall. Like many of the valleys in the late fall you don’t see a human… ever. There’s never anybody around. I took my dog at the time, Joss, and Terry and I were riding towards Leeman Lake. There was a moose in the creek before you got to where you have to cross to go up to Leeman Lake. The moose took off and unfortunately the dog took off after the moose. But nobody’s around… Anyway, Terry and I continue on and come across some people further up beside the creek, soaking wet. They said that a moose came charging up the creek and they thought it was being aggressive towards them, so they actually jumped into the water to get away from this moose. And then bounded a dog. I had to admit it was my dog and apologized profusely. They were not happy, and they were camping, and they were wet. I said “Come on back to the cabin, bring your stuff and you can dry out and get warm at the cabin”. Which they did and we got visiting over time and gradually I think their anger wore off. That was not a shining moment for both my dog or my history.

I’ll tell you another great one, and not too many people know about this. When I was in the Tonquin in 79, Marv Miller was my boss and quite a character as everybody knows. Marv came into the Tonquin with me in mid summer sometime, and he had his dog Partner. So we’re riding up and when you come into the Tonquin, you go up through a series of switchbacks and then you break into open alpine meadows for quite a ways, before you go down to the cabin. We’re riding across those meadows, and Partner is off on both sides of the trail in the distance chasing squirrels. We come across about ten hikers, a large group. We’re visiting with them, and Marv is asking if they’ve got their permits and all this kind of stuff, and Partner appears with a squirrel in his mouth. Without missing a beat, Marv said “Alright who’s dog is that?” All these people look at each other and say “It’s not ours.” Marv said, “Well I better find out whose dog this is” …About 400 yards down the trail Marv broke into reams of laughter. That’s where I learned that sometimes you really have to think on your feet. That was a good one in my mind, but there were lots of them.

Other stories, I think one of the more interesting ones, Banff’s park planner, Mike Murtha asked if we could take him by horseback to the far side of Palliser Pass, down into BC to look at an area that UNESCO was thinking about including in the World Heritage site. Ian Pengelly and I took Mike Murtha to Palliser cabin and then down into the BC valley, on the other side of Palliser Pass. I forget what valley it is, but we had a long ride in pouring rain. Seven hours of riding in pouring rain. We met up with John Niddrie, who was outfitting for BC Parks because they were meeting us too, to go into this area. We had to sleep in the horse trailer because it was raining so hard. No food for the horses and no way of getting up to the valley Mike was evaluating. Finally, the weather broke a little bit, but John and the BC Parks people had bailed, they couldn’t take the weather anymore. A helicopter flew in some feed for our horses from Banff.

SH: I was on that helicopter.

Ian: Yes you were, and we flew up into the lakes. I forget the name of the lakes.

SH: Limestone Lakes

Ian: Yes, it was an absolutely spectacular area and we hiked back out, got on the horses and rode to a trappers cabin to spend the night. That night at the cabin we were sitting around telling stories and Mike Murtha said, “Can you tell me some of your horse horror stories?” You have your usual things like horses bucking boxes off or the horse shying and you getting thrown, but nothing too serious. The next day we’re riding back up over Palliser Pass from the BC side, and we are about a quarter of the way up and because it had been raining so much and the trail was quite steep, it was muddy. Slippery. I said to Mike Murtha, “I think you should get off and walk.” I like to walk uphill especially if it’s slippery. Mike felt uncomfortable about getting off on the upside, or the opposite side that you would normally get off and on a horse, to step onto the bank. He had Frank Burstrom’s black horse, I forget its name, but it was a real steady horse, but he didn’t want to get off, so we continue on up the trail and it wasn’t five minutes later, the horse slips and down goes Mike. I was in the lead and Ian (Pengelly) was behind me and said, “Ian you’d better come back”. So I go back, it was hard walking because it was so steep, walking by all the packhorses and nowhere to tie the lead horse. Anyway, walked back and there’s Mike Murtha lying underneath this horse that had slipped and fell downslope. It was like one of those moments. Oh my God, how do you remotely begin to get Mike out of this predicament. I went up to get my ax, because I thought we were going to have to kill the horse before it stomped Mike in getting up. Ian unhooked the cinches on the horse and somehow that horse jumped up without stepping on Mike and Mike was left in a little ball, still on the saddle on the ground. We got him attended to, to see if there were any injuries, which there didn’t appear to be, but he was the color of a ghost, as any of us would have been having gone through what he did. He didn’t want to ride that black horse again, so we saddled something else that we knew was very quiet, put him on, and rode him up to Palliser Cabin. We got to Palliser Cabin and Mike was still pretty pale, so Ian and I decided that we better call on the radio and get Mike flown out just in case there was anything wrong, plus he was not feeling comfortable riding anymore anyways. So the helicopter came in that evening and flew Mike out. The next day we got a radio call that Mike had been taken to the hospital and that he had a punctured lung from a broken rib. So it was a good thing we got him out. But after him asking what was the worst wreck? That was the worst wreck.

But not too many horror stories … lots of good horse stories but fortunately nothing super dangerous that I was involved in. As we all know things can go south very quickly.

SH: One of my favourites with you, and an example of how technology changed, was you calling me one day on the satellite phone and you were out with Ron (LeBlanc) and had gone up to a ridge top. Do you remember the eagle?

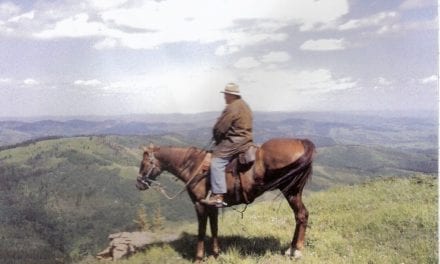

That was at Indianhead tent camp in probably late September. The Indianhead Creek area is interesting in that it and Condor Creek, which is out in the Province, were on the major migratory route for golden eagles. It was not uncommon for anyone on boundary patrol to see eagles shooting by up high as they continued on their way south. Ron and I and another fellow hiked up towards the pass above Indianhead Creek, where hunters can come up on the other side. We hiked up there and continued on up the ridge. Ron wanted to do the peak and I was content to just sit and glass the slopes. It was a very windy day and I kind of hid myself behind a big rock and was just sitting looking down at Indianhead Creek and the ridges, glassing.

A golden eagle zoomed by about 45-50 feet away and it suddenly turned and came into the wind towards me, and I realized that it must have thought I was a carcass or something like that. So he was coming in for a lunch break. My camera was close, but not really close and I had to move to try to get my camera. This thing was coming closer and closer and closer. At about five feet away, it suddenly realized that I was moving, and it took off, and shot off down the valley again. It was one of those, almost spiritual moments. Lots of people laughed about that story, because it thought that I was a carcass.

As an aside, my last trip into the backcountry was with Ron and Bob Haney and Rick Smith. We basically rode from the ranch to Scotch Camp, and from Scotch up to Divide. Bob and I took off down valley towards Indianhead. Rick and Ron I think decided to stay a little longer at Divide for some reason. Anyway, that night Bob and I were at Indianhead and it rained unbelievably. Big floods. Ron and Rick had to ride down Peters Creek with rocks and boulders coming at them like bowling balls, and then got to the Clearwater River and then cross it, which was no easy feat. Anyhow, they got to Indianhead. Bob and I were going to go onto Clearwater, but we got up to where Clearwater Lakes empties into the Clearwater River and it was way too deep and going way too fast, so we went back to Indianhead. Next day down to the provincial cabin, on the Clearwater, and as we were riding in, I noticed a few golden eagles and we stopped and had a look. Sitting outside at the cabin, having a cold one or something. There was a few and then suddenly there were 15 or 20 circling the peak, getting ready to head south, and it really impacted me that I’d likely never be in that country again. It was difficult for me and probably difficult for Bob because I was crying, crying hard.

SH: I loved that story.

Ian: Ya, Indianhead tent camp was always high on my list of favourite places to go. Indianhead, that whole area on fall boundary patrol was pretty special. I loved doing it. Anything else?

Jean & Rick Smith, Ian Syme at Divide Cabin.

SH: No you tell me some stories. I’m making you tell the ones I know.

Ian: I might have to think about some. There’s some, with staff, and I’m not going to mention any names, but when I was in Lake Louise, I remember getting a call from the Superintendent about a complaint from somebody, a backcountry user, that a warden on horseback had stopped them and was asking for permits, and giving them heck for maybe hiking without a permit … I forget but something along those lines. The clincher of it was that the warden didn’t have a shirt on. It was a nice day. So, here’s a guy riding along without a shirt or hat on. He popped his hat on and asked for appropriate permits …. they were not impressed. The fellow and I talked when he got off shift … and giggled, but he learned his lesson, I didn’t need to elaborate. Superintendent was briefed on the “disciplinary discussion”. Those were some of the human resource fun things that you had to deal with, no shortage of that stuff.

It was a wonderful experience and great people. What was probably the biggest thing, one of the biggest things that I enjoyed not only in my career in other parks, but certainly in Banff, was most of the staff were absolutely exceptional in what they did.

SH: Okay, so do you want to talk about how the Warden Service changed over the years?

Ian: I think the changes that were evolving during the late ‘90s and 2000s as everybody’s familiar with, revolved around health and safety. In things like public safety in Banff, there was a transition, and I worked with Marc Ledwidge through that transition. We had the same approach. It was controversial at the time, but we used to take some people that had some aptitude in public safety, and then send them off for four years of mountain guide training, to get their guide’s license, and then they can qualify to lead not only rescues, but training as well. Marc and I kind of realized that there were a lot of full mountain guides out there, that had got the educational background that the Warden Service might require, so we started doing competitions for full mountain guides. That was sort of in recognition that the specialization of the Warden Service was pretty much fully underway, largely health and safety protocol driven. The staff we trained were exceptional, but we just couldn’t continue with that level of development and have enough qualified Public Safety staff.

The firearms issue was not an easy one, for both staff in the hearings or for staff that were back in the office trying to figure out the new world. Where we were out of law enforcement all together which was very, very tough on a number of staff. I remember working with the Staff Sergeant in the RCMP at the time, because they were supposed to help pick up some of the slack when we were not doing any enforcement. S/Sgt Joe McDonald, a Newfoundlander, we couldn’t have asked for a better guy to be there at the time. They did what they could, but it was an awkward situation for them. Then we kind of got back into it with the use of shotguns but that got collapsed in the national hearings. In and out was just not fun. There was maybe a solution years before, but probably there were political reasons where that couldn’t have been advanced. I’m not going to say that definitively, but I know it played a part in larger federal politics. In the end the move towards the Warden Service being law enforcement only and the rest were resource conservation, was in some ways inevitable, in retrospect.

The notion that everybody did everything … I know you and I worked on presentations for management in Banff Park, where for a six month seasonal that came back on to work, they had X amount of holidays that they had to burn through. They had health and safety training…everything from firearms, to first aid, public safety, to cultural resource management, law enforcement refreshers, wildlife handling, all those things that the Warden Service was involved in at that time, plus departmental training on human rights and workplace diversity. It turned out that for a six month warden that showed up every year, I probably had them for work, maybe for four months, and the training and leave and overtime in lieu took up about two months of their time. That was probably not sustainable in the long term. That’s why there was increasing specialization within the Warden Service, driven by training requirements and health and safety requirements. It wasn’t pretty the way it evolved but I think it was inevitable that what happened was going to happen. I’ll leave it at that. There was lots of nuance in there that was hard, but it is what it is.

The big thing that we as old wardens need to remember, or we should try to remember is that….I remember speaking with some of the folks that were left in Resource Conservation and not doing the warden role, not wearing the warden uniform. Young people like Dylan Watt, and the absolute awe for the job was still there. The same awe that most of us had doing multiple roles, he had for the role he was doing. I think he was working on the bison project, or doing some backcountry stuff, or a little bit of fire stuff. The people that came to Parks Canada after the significant changes enjoyed the job as much as we did. I think that that’s pretty telling about the sort of work that we were involved in. I’ll leave it at that.