Laura: When you say, “what you like doing”, what does that mean? Being out in the field?

Kevin: Waterton’s a little park and it’s surrounded by a lot of private land… and there’s neighbours on the American side, on the BC side. So, it’s got a lot of cross-boundary kind of issues. And, I was hired as the conservation biologist so we focused on the conservation piece. For the first few years, I was really working on neat problems- challenging problems…trying to figure out how to get conservation outcomes in that complicated landscape. For example, wolves reappeared in the park from the US side, and we were trying to figure out how to keep them alive. And wolves were not popular in the neighbourhood. So, there was this thing about working with the ranchers and working with Alberta Fish and Wildlife, and we got into huge really interesting issues about land conservation.

All of a sudden, the real estate industry discovered that there was private land adjacent to a national park. They started getting ambitious about it. So, I had to figure out how to fend that off because we were going to lose the health of that park if we lost those surrounding private lands to a subdivision. So those issues were really something you dug your teeth into to figure out solutions, form relationships, and negotiate with diplomacy. It was just fun, you know. It was hands-on, meaningful conservation work in a complicated world. So that was really great. But then, at one point, maybe someone had a talk with Bill and Bill said, “I’m going to have to take on more of that kind of stuff and we need to get you more focused on what these jobs are meant for. We need a monitoring program for the park to monitor ecological integrity.” So, there was this sort of ‘shrinking of my world’ away from the really fun stuff back to what I’d actually been doing with the CWS years earlier. At that point, I started to lose interest because I wasn’t really motivated to go back to doing things I’d been doing ten years earlier.

Laura: Oh okay. Because that’s what you said was one of the things that you loved.

Kevin: Well, it was right for the time, in my twenties, but I’d gotten kind of engaged in some of the more creative challenges. That was one of the great things about going to Jasper. With the Ecosystem Secretariat position, you did get to work on strategic issues. For a while, I was on the board of the Foothills Model Forest, even as chair for a while, and that’s working across boundaries with difficult, challenging relationships to try and get conservation outcomes. That stuff was fun!

The reason I liked the earlier stuff, the field work with CWS, is because I was fresh out of university and I was absolutely free. I didn’t have anyone breathing down my neck, we had like 30 hours of helicopter time a year, and I had to get out there and explore the entire park in every season. You don’t get jobs like THAT too often! And it was the perfect time- a huge growing time for me in terms of wilderness skills.

Laura: And that was Jasper?

Kevin: Yes. And then again in Rev-Glacier after that.

Laura: So, Jasper has been the most special park in your life, would you say?

Kevin: No, I would say Waterton. Jasper was the one my career kept me going back to, but I never felt completely connected there. Jasper was a funny one. For one thing, all the streams were glaciated and I like clear streams. I’m a trout fisherman. So, there was always that thing. And, then the other thing is that it’s got some beautiful, wild country… but it’s really quite remote. So, to get anywhere good, it’s a multi-day trip. So, you always felt like you were being sort of held off by the immensity of the landscape. Whereas in Waterton, it’s got incredible biodiversity – and everything is RIGHT there. The only problem with Waterton was that it didn’t have that wilderness hinterland feeling that Jasper had. In retrospect, in some ways, the park that had the most influence on me – and yet didn’t end up being my favourite, was Banff. Banff was a little bit of both. I started there as a student at U of C. In those days I would take the Greyhound or hitchhike out here on the weekends, and hike up the Cascade fire road and camp there, and hitchhike back to go to classes. And, I used to do that a lot.

Laura: Well, it was so close to where you grew up. So, why do you say that Banff had the most influence on you?

Kevin: Because it got me when I was young. That’s where I got started. That’s where I got my first backcountry trips… all those solo adventures up the Cascade Valley. And, it was the one where I came to the end of my career… (It was a place) where I did some good things and didn’t do other things well. It was a point where certain things came to a head. I was really fortunate to be there when the time came ripe to sign the Letter of Understanding with Stoney Nakoda First Nations, inviting them back into their own damn park. That felt really good to be there for that moment. Also, I was really happy with the 2010 Management Plan, although I wasn’t happy with how I did it. I micromanaged it. Kind of grabbed the pen and left the park planner feeling abandoned. I still feel bad about that, but I felt good about the plan that we produced. And the outcome of it. That whole bison reintroduction came out of that management plan. So, I feel good about a couple of things that happened in Banff. It was the launch pad for my career, and the landing pad. But I would say that in between, the best years were those early years in Jasper, and then those good years in Waterton.

Laura: Pretty well-rounded as far as what these different parks brought to you.

Kevin: Yes. I feel lucky.

Laura: That sounds pretty special. One of the questions here is, what didn’t you like about being associated with the Warden Service?

Kevin: What I did like about them was the warden service culture, which is a collection of really devoted outdoors people who work as a team. There’s lots of different individuals that work in the warden service…and there’s a lot of diversity… a lot of different kinds of people working there…but they add up to a singular culture. So, not everything I might say that’s positive or negative applies to every warden, right? But there is a global sense of things that developed over my time.

What I really liked about working with the warden service is that they are what Jane Jacobs would describe in her book (Systems of Survival) as a guardian culture. So, when you look at what ‘guardian cultures’ are, they are place-based, conservative, valuing competence, distrustful of outsiders and deal-makers, valuing tradition and continuity, things like that. Hunter-gatherer societies tend to have guardian cultures, while those based on crop agriculture and trade have what she describes as commerce cultures. She (Jacobs) was looking at cultures at an anthropological sociological scale but it works at an organizational level too. And I came to think that one of the sources of some of Parks Canada’s problems were that the warden service is a guardian culture embedded in an organization which, at least at the management level, is more of a commerce culture. They created some of the disharmonies that developed and became problems sometimes.

Guardian cultures are ones that are rooted in place, they value technical competence in skill. They have strong internal loyalties, and they are defensive. They are protective. That really describes the culture of the Warden Service. Guardian cultures of that sort can become elitist, because they respect and rely on one another and face outward at things that threaten them (or in the case of the warden service, that threaten the parks). The sorts of responsibilities they had was protecting the park from poachers, where you need law enforcement experience, and from fires, where you need fire skills, protecting the visitors from wildlife conflicts and avalanches where you need those sorts of skills. So, by nature, they had to develop technical competencies and rely on one another, which builds strong internal bonds.

When you’re working in areas of high technical demands and high consequences of failure, you quite often find yourself out of your depth. You’re often dealing with situations that you’re not ready for, that you don’t feel skilled to deal with…and yet, you gotta deal with them. And so, you really have to rely on each other, and you really have each other’s backs. So, this creates those strong loyalties and a certain level of defensiveness. What I liked about the Warden Service is that it created a sense that-these are people you want to be associated with because they’re doing the hard stuff. Sometimes in spite of themselves, but usually successfully because they are so dedicated to the role and they can rely on one another to figure stuff out.

As I say in this new book of mine (Understory), it reached the point during the arming issue that the CEO saw park warden culture as Parks Canada’s biggest problem and they were. But they were also its biggest blessing. And that’s the thing; the warden service has always been both the best and worst of Parks Canada. The problem is that it’s very easy to start to think that you work for the Warden Service and you don’t work for Parks Canada. And because of the need to develop these technical competencies, there’s an elitism that develops. So that can become exclusionary and that becomes a problem if some wardens start to see other people as second-class citizens within Parks Canada. So that can create a conflict. I remember when I started out there was conflict between the Park Naturalists and the Park Wardens. The Park Wardens were the ‘‘real men’ and the Park Naturalists were the townies. There was that sort of thing. That was the culture in the ‘70’s. (The flower sniffers and those who actually knew how to saddle a horse.) That came out from time to time to different degrees in different parks.

Laura: But you mentioned this was not your experience in Kootenay

Kevin: Kootenay was small enough. And, the personalities were such that …It didn’t have the ‘hero making’ environment there. It didn’t have the big mountain rescues that they had in Jasper. It didn’t have the big fires during the time I was there. It didn’t have the things that created ‘otherism’, you know. And they just had good personalities: Ian Jack, Larry Halverson, Byron Irons, Ron Davies – they were the kind of folks that just had fun with each other all the time, even while doing good work.

The things I liked about the warden service sometimes were also the problems. And, it really depended on where you were. Sometimes Jasper was the problem. All these backcountry wardens that felt that the backcountry defined who they were and that management had no right to change that. And sometimes Banff was that way. It seemed like the ‘otherism’ was most pronounced in the bigger, more complicated parks. Which probably makes sense; they would have more complex programs and more divisions – more visitation… just a lot more to manage.

Laura: Right. I guess you kind of already answered the question “What connections did you have with members of the warden service over the years?”.

Kevin: I can touch on that a bit. When I moved to Jasper on the Wildlife Inventory, Don Dumpleton was the Chief Warden. He was not very welcoming. He was not happy about the fact that they had to put up with these biologists. It was a bit of an interesting thing because of the research program that CWS did in those days … all of our reports that we produced (from Parks Canada’s point of view, our work was to produce reports that they could use… that was our job). Well, a report is a capital asset. So, all of our work was funded out of the capital budget. Only because of that, our part of the Parks Canada wasn’t available to buy ‘stuff’ (tables, signs, horses, trucks, etc.). So, there was always a resentment among some people in Parks Canada’s that their capital dollars were going to pay operating costs for the Canadian Wildlife Service. And looking at it objectively, they were right. I think that was partly why Don was so chilly to us CWS types. Our salaries were being paid (by funds) that they could have used to buy more ‘stuff’. They always need more stuff. Things wear out. Parks are hard on things.

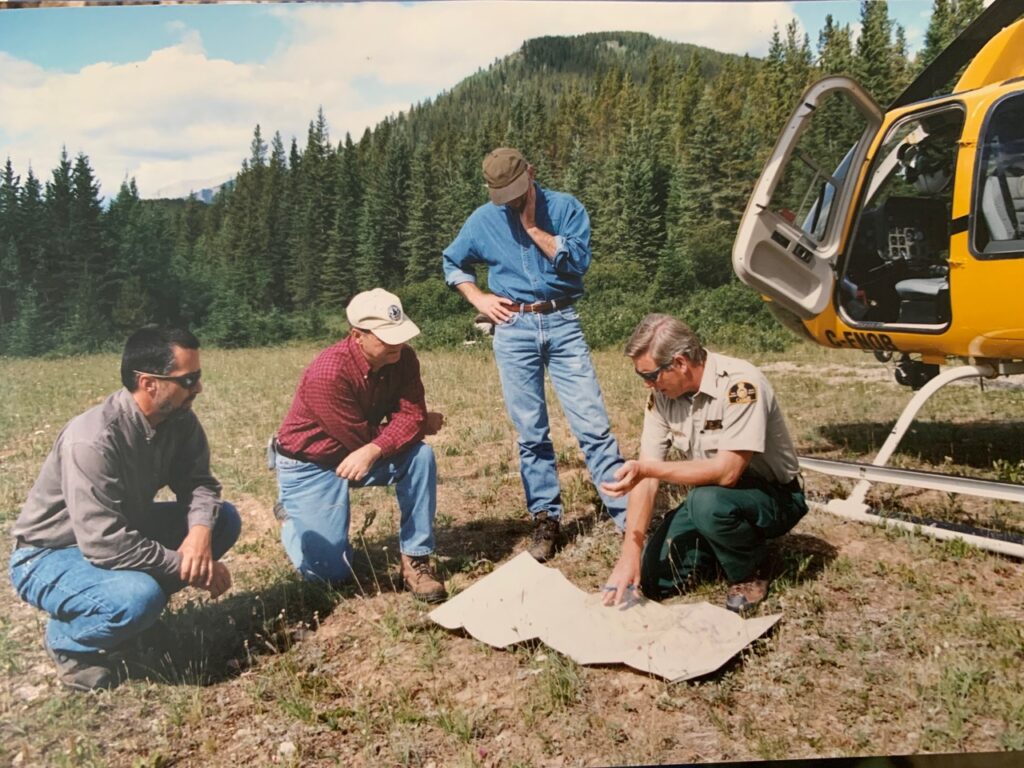

Kevin Van Tighem on the left, Dave Smith on the right, not sure who the other two are.

Jasper National Park (fire planning) about 2002.

Photo credit: Kevn Van Tioghem

So, I think that’s where Don was coming from. He figured we don’t need biologists…We don’t need ‘know-it-alls’. We’ve got wardens. They know what they’re doing. And, you’re taking up money we could have been using for other stuff. So, Don was not that welcoming.

Jim Boisseneault was the guy he put in charge of liaison. Jim was fine. He was businesslike. I worked well with him. It was always just scheduling helicopters, coordinating cabin use, things like that…

I also worked with Wes Bradford. Wes was the wildlife coordinator. Wes was just dynamite to work with – I developed a ton of respect for him. He never led with his ego because he knew who he was; he knew what he was competent at, and he just wanted to be professional and diligent. He knew that we were there to study the wildlife that he liked to study…So we were just colleagues. I really liked working with Wes. He was a good guy. Well, we both liked sheep hunting too, so we had stuff to talk about.

A really good interview. Kevin had challenging management decisions for a challenging time in Parks Canada!

Good job Laura!