“You talked about climbing Mount Logan, are there other really memorable events from your career as a warden?”

(20:23) Well, we’ve had some rescues at Kluane where we had to rescue our own. We had training programs and sometimes the training programs are as high profile as the programs of the mountaineers who come to climb the mountains. We climb the same areas and take the same risks. We need the experience so that we can be able to function in those areas, and they can be dangerous in their own right, being in that kind of environment. We had a situation where some other people got injured and we had to rescue our own, but we never lost anybody.

“I did speak to Ray Frey and he spoke about that, when you had to rescue some of your own.”

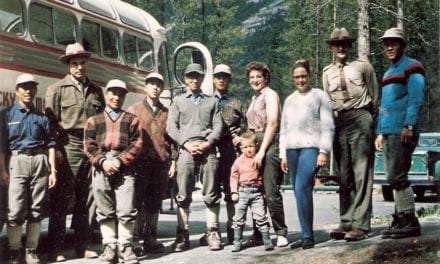

Yeah, he was with us on one particular group, with Willi Pfisterer and Lloyd Freese and Tim Auger and Peter Perren. Who else? You are taxing my memory now!

“I just interviewed Tim when we were in Canmore in March and he spoke a bit about it as well.”

Yeah, it was pretty hairy, it was extremely hairy actually. It is one of those things that until it happens, you never think that it is going to happen, but that is exactly what it is all about with that. I’ve always had the (belief) that if you don’t do anything, I guess nothing can happen to you, but even then it doesn’t seem to work. I never had a qualm about going out on a rescue to try and help and rescue people who get out and do things. I always feel that if it wasn’t them, it might be have been me because I like to get out in the mountains and do things as well. So I guess that’s just the way I’ve always seen it. I’ve never seen it that it is them and us in that way. I just see it as it might have been me somewhere else doing something. I’ve always looked at it that way. I’ve just been lucky that it hasn’t particularly been me as such…but it can happen at any time too. When you do self rescue with your own people, it puts a different spin on it, it is a different thing. When you rescue other people, you don’t know who they are and you just get out and you do it. You don’t pay attention. But it is like working with family (when you have to rescue colleagues). I worked with the Ambulance for 15 years and the last people you ever want to have in the ambulance are members of your own family…

“Yeah, that is what I was talking about.”

(24:18) I don’t know if you talked about the one where Auger and those guys went down the ridge, off the east edge of Logan? Was that what you were talking about? I don’t know if you know who Larry Tremblay was? He was the Chief Warden at the time here. He had been a warden for many, many years. He was a cowboy before he became a warden in Alberta. Just when we ended up picking up Auger and brought him back in the helicopter, Ray Frey was there too, at the airport at Haines Junction, Larry Tremblay had tears in his eyes when he came to meet us. That is the power of dealing with your own…to me I will never forget that because he was one of those kind of guys that I don’t think he had tears in his eyes any other time. So those are the kinds of things that a lot of people don’t realize. You get out and you do it, but there is a lot of emotion involved in that and you don’t know it until after it is over…It is one of those things that you don’t realize until it is over how much it meant or what not. You are so busy doing what you are doing that is just doesn’t enter the picture. It is only later you take a look at the (big) picture and you say “Wow, this could have been worse than it was and we are lucky to be back.” That is something I think is important for people to realize that when you do things like that a lot of times they go out and see you after the situation and right away they will say, “Oh yeah, that’s okay that is what they do.”

“That makes sense and few other people have spoken about it as well, especially everybody involved in the rescue stuff.”

Well sometimes it is later when it suddenly hits you as to what you really have been doing. It is hard to describe, but anyway… Yep…I used to feel so sorry for people, if you rescue people, they are hurting, if anybody is hurting it is not a nice thing…it is the same thing working on the ambulance. I worked on the ambulance for 15 years as well, during the time I was with the park. It is that same kind of a feeling. Thank god you are not the one there. But that is what people do when they get out in the rescue business. They have feelings for it and that is why they do it.

“What did you like best about being a warden?”

(27:51) Well…the rescues and the fraternity of it, but we also did some rescues in Alaska. We worked with the rangers in Alaska quite a bit. I trained with them. And it is just being here at Haines Junction for example where I live right now, looking at the mountains. We were up there in the mountains, doing things in the mountains. That is what I liked and also the discovery, and the fact that not a lot of people had covered the ground that we did. Especially being of a First Nations background, I even sat on negotiating situations between the government of Canada and the First Nations to talk about the claims over the mountains here because the First Nations people hadn’t been in there for 30/40 years. It was a game sanctuary before it was a national park, and as a game sanctuary the First Nations were not allowed to trap or hunt in there. So they actually didn’t go in there anymore. My mother was a trapper and my father was a trapper. There is actually a lake in Kluane called Louise Lake named after my grandmother. But no family had gone in for 40 years. So that for me on a personal basis, opening up a piece of history (as a First Nations person and a warden, was very important). It wasn’t regimentally closed, but it was basically closed. The economic reason for going in there wasn’t there anymore. If you couldn’t hunt in there, then there was no reason for them to go there anymore and they didn’t. In that way, I had a different perspective on the park than most everybody else.

“When did that start to change, that they (Parks Canada) realized they had to recognize First Nations rights to that land?”

Well, that was after negotiations, land claims negotiations, after 1990…1993. They signed an agreement with the Champagne and Aishihik First Nation that I am member of. I am actually a co- signer of the agreement, because I was Deputy Chief at the time. So some of the unique situations I’ve been in (have been a highlight of my warden career) and I’ve seen it from two perspectives…I had an aunt by the name of Kluane, my oldest sister’s name is Kluane…Kluane is a family name way back and then of course the national park and Kluane Lake. So Kluane has to be a special place for me and my family, which it is.

“All that time you were a warden in Kluane, were you always based in Haines Junction or were you in different places?

(31:17) I was based basically in Haines Junction. (Haines Junction is the main base and that is where we operated out of for search and rescue and whatnot anyway in the summertime for sure. In the first number of years we were fairly busy with training and then actual rescues too, so the base here is pretty well where most of us stayed. We had kind of a station at Burwash, there were a couple of warden families who lived there year round.

“Was there anything that you didn’t like about being a warden?”

(32:05) Well, at first I didn’t think I would like being in the uniform in a place with First Nations people and having a First Nations background, because uniforms and First Nations, didn’t always have a good history together. (But I think it was a different perspective, it was more information…and one thing about a guy like Larry Tremblay, he was into talking to people. He thought it was very important to talk to people no matter what and where. And that’s what it is. So we did a lot of communicating, even our reports had to show that we did (Public Relations) PR. We had to have a certain amount of PR time in our reports. You know that’s what it was and the locals kind of got relaxed to the fact that we were there and it became a lot easier. One of the frustrations I did have of course was it took so long for the cultural side of it to catch up to the other side of it. That was personally frustrating for me…Other than that I didn’t have too many problems, not as much as I thought I would have. The thing with the police side of things and the First Nations, they didn’t have a good history. And I spent seven years in Mission School myself, so I knew about the enforcement side of things. But like I said our job was to talk to people, communicate and that sort of thing. The other part is I guess we were a little bit lucky in the fact that we didn’t have to come along and tell people they couldn’t go in the park because it was already established before we got there, before it became a park. So you didn’t have that same bad guy situation. Of course, in Alaska and some of the new parks they made over there in Denali they actually had to tell people they couldn’t do things anymore. There were pretty heavy feelings and mistrust between people over there. Talking to the rangers, they had it a lot tougher that way…People got used to doing certain things and then an agency shows up and says, you can’t do this no more.

“Did your wife enjoy the warden life? Like did she worry about you on those rescue calls?”

(34:59) Anytime I had to go out on a call of any kind, she made sure the lunches were made. She made enough for me and whoever else might be along. I wouldn’t have been able to do (it without her). She was absolutely supportive along those lines as well. There were times when we would spend a few weeks out in the backcountry, or climbing a mountain, so she would take care of everything at home. That was important and they (warden’s wives) did play that role, they were very supportive of us. So that helped…We were doing dangerous things, but she never did say, “Don’t go.” She just said, “What do you need to be comfortable when you do go?” And I think that was important. There was one of our pilots that never seemed to have a lunch, so she would always pack a lunch for him…Just that type of thing. Her name is Merrilee.

Was there anything about the warden service that was important to you?”

(36:52) Well, what was important was that Canada had a service like the warden service. I think that was very important. We were spokesmen for Canada and that is what made it easy for me to become involved with the warden service. There were very few First Nations involved with the warden service back then so they were kind of seen almost like the cop guys in a way, but that’s not really what the role was. We had enforcement too, but it was more on the land and dealing with people, and dealing with wildlife, and dealing with what is out there. That to me is the image of Canada. That is what is so disappointing about Canada dropping the warden service. They don’t have that same kind of a focus. Like in the US there is Smokey the Bear, but Smokey the Bear is the rangers. There is a support group behind it and the warden service (does not) stand alone, by no means because it had the interpreters and all that. They were all part of it, but the wardens were the focal group. That’s what that was. There were some people who had concerns about that, but the real thing is somebody needed to be the focal group and that is what they were and I don’t think they have that now…You have to go to each department for what you want. The warden was the catch-all and then you could end up going to what department you needed. But if you saw a warden, that was the park. It didn’t matter what the question was you started with (the warden) and I don’t think you have that today. Everybody wants to go to an office to ask a question. I think that is really a big loss for Canada.

“Again that is something everybody I’ve spoken too has said.”

Yeah, it is and I don’t understand how they let that go.

“This ties into the last question, is there anything about the warden service as you knew it that you would want future generations to know?”

(39:37) Yeah, that there was a group of people out there doing that very same thing that we were just talking about. As a First Nations person, I don’t know who the focus is now. So I can’t encourage the First Nations to really get involved in Parks because I don’t understand what and where, like it is a complicated system now. You know each department, well, I don’t know what they have for departments even…I have a hard time trying to encourage anybody to get involved with Parks because I don’t even know where to start with it. I have a cousin right now that is just hiring on for summer employment, my niece’s daughter, and I am not sure what her job is even yet. There are a lot of questions out there, so it is hard for me to encourage people to get involved with Parks because I don’t understand what is going on with the Parks. I am really concerned because as a First Nations person, I would think that there should be a lot more brown skins around here in an area (that is predominately First Nations). It’s hard for me to encourage it because it is pretty confusing for me and I actually went through the system. If I can’t understand it, how are they going to understand it? So that bothers me pretty badly. Even though they have retained a number of First Nations on, it doesn’t have a focus…there is no focal point that I can see. They are each doing something different. So we have now come on stream, but the stream is really muddy. And I am talking as one of the first people appointed to the management board, which is co-management from the First Nations and the national park.

“Would that have been in 1993 or in the early 1990s?

The early 1990s, I think right after the agreements went in and then they formed a co-management board.” They held an agreement with the First Nations of the given areas, especially in the north. All the northern parks seemed to have had that. The Haida Gwaii was one of the big ones. As a matter of fact, the Haida Gwaii probably managed more of a park than almost anybody else. But they negotiated for that, they held out for that. I was actually one of the people that told them to do that…you don’t know what to go for if you have never had experience. After I met with the different First Nations like I did in the north, I went down to the Queen Charlottes to spend a couple of weeks there talking to the Chief and Council there. What I did with them was (I said), “I am not telling you what to do or what not to do, I am just saying as a First Nations person you go after what you feel you need and negotiate with the park for what you need.” (Parks) was more or less moving in and the Haida Gwaii didn’t like it. I said, “That’s right, you guys sit down and you negotiate. You guys are going to be the leaders of the area so you need to talk to them.” And that is what they did. They wouldn’t agree until they had (what they wanted). They held out for quite a while. There was a lot of conversations going back and forth between the park and the Chief and the government…I was there as probably one of the first wardens in uniform, I wore my uniform one time for our first meeting and (they said), “We’ve got nothing against you, but we don’t like what your government says.” I says, “Well, that’s good, you have to go for what you want.” I wasn’t trying to be on one side or the other, I’m just saying, “You guys, as First Nations, you need to do what you want to do.” I haven’t been involved in it since then, but I understand they really carry a big part of the ball over there. And I could see that they could. The Haida are pretty powerful people. You see my situation was because I was part First Nation they asked me to come over to negotiate and talk with them which I did as a performer and a dancer, this is what they saw me as, but I was also a Tlingit and they are Haida. The Tlingit and Haida have had a thousand years of sometimes good times and sometimes bad times, and I sure didn’t want to go over there as a Tlingit park warden and tell them what to do! That is why I said, “You guys see what you want to do and then you negotiate with those guys.” That is kind of how I put it. Well, I thought it was because otherwise I wouldn’t have gone if they just expected me to be a spokesperson for the park, without that cultural side of it. Then I wouldn’t have gone, I would have got someone else to do it. But I did want them to know that the park was an opportunity and the park had value that they could utilize. That was the way I wanted them to look at it. I did a slideshow for them and I said, “This is what we do with Parks and this is what wardens do and this is what interpretation does. We go out on the land and we do this and we enforce. So all the things you do as a park warden, or as park personnel, is get out on the land and protect the land, take care of things, see that people are safe and all that. That’s pretty good!” That’s what I wanted them to hear. “It is essentially good and you guys can do it.” That was my message. They liked what I said because I got along quite well with the Chief and his brother there. I kind of knew him a little bit before anyways. There is another guy down there called Guujaaw, he is a spiritual leader, he is a powerful guy. I actually performed with him in the past on a different occasion. So I had some roots there, I knew some people there which makes a big difference when you are negotiating. I guess I was a negotiator part time too. I did go to Old Crow and do some of that and that sort of thing.

(47:52) I guess the final question is, “Why would I leave?” I didn’t end my career, I quit. One of the reasons was things were getting a little quieter here, it was changing and the computer didn’t sit well with me. I am dyslexic, I couldn’t write anything and it was starting to head that route. So I started realizing that I am not fitting in the program anymore. I could see that it was heading that way, so I just left.