This Oral History interview was funded in part by a research grant received in 2022 from the Government of Alberta .

Park Warden Alumni Society of Alberta

Oral History Phase 11 Fall 2021

Phone Interview with Monique

Date/time: April 5, 2022/1000

Interviewed by Monique Hunkeler

Place and date of birth? Edmonton, July 1952.

MH: Where did you grow up?

GI: I grew up in Edmonton. Went to elementary, junior high, high school and eventually graduated from University of Alberta in Edmonton.

MH: How did you become involved in the Warden Service? Which national park did you start working in?

GI: During summer in high school, actually, between grades 10 and 11, a couple of buddies of mine didn’t really know what to do for the summer and we saw this advertisement at the Hostel Shop in Edmonton, one week of climbing one week of hiking with instructors and guides. So we took that and immediately fell in love with it. This was up in Jasper. When that was over, we decided to hike the Skyline trail, but the two buddies that had been with me on the courses couldn’t come back to Jasper for different reasons, so I decided to stay in Jasper and got some great advice from a woman at the information center back then. She said, “Why don’t you just think about who you’d like to work with the most, and go there first, and see if they’ve got any work.” This would have been the end of July, so I thought about it for a while and decided I wanted to work for the Park so I went to the Parks Office and they actually had a campground attendant position that had just come vacant. That started me off and it is through those summer jobs that I got to know more about the Parks Service and the Warden Service. I had actually lied about my age. I had just turned 16 and I knew that you had to be 18 to work for the Federal Government, so I told them I was 18 and started working the summer of 1968 and every summer since until I retired 41 years later.

I started in Jasper and was there many summers, and then as time went on, I finished high school and then when I started university, I became a Park Naturalist starting off in Yoho National Park and then moving back to Jasper National Park. After three summers as a Park Naturalist, I applied for the Warden Service and got on as a Term Warden in Jasper and then out to Pacific Rim National Park as a Seasonal Warden for a couple of years and then started full time in Lake Louise in Banff National Park in the fall of 1978.

MH: What made you want to join the Warden Service? 0340

GI: A bunch of reasons. Having worked at that point for Visitor Services in campgrounds, I also had one summer working as a garbage truck driver under trades and utilities and then back to campgrounds. I had all seasonal jobs, but it gave me a pretty good understanding of what was going on in the Park. And it just seemed that the Warden Service had the greatest role and responsibility for management of the landscape as opposed to management of the people which at that time was primarily Visitor Services, and that just had a greater interest for me. Then of course, particularly working as a Park Naturalist, I did quite a bit of work together with the Wardens at that point. That really gave an appreciation for what land management, ecosystem management was like, and that just led me into it. Plus, one summer working as a Park Naturalist stationed at the Columbia Icefields, there was a group of scientists there from MIT that were doing some research for the NASA Apollo Moon Program. They were doing their tests on the Athabasca Glacier because they felt that it would react seismically as close to the moon rock as possible. So that got me quite keen on going into the sciences at university, took me into physical geography. That was a really key moment, just being able to interact with those scientists from MIT and understand that outdoor research in a wide range of sciences are possible within the Parks Service, and that definitely led me into going towards the Warden Service.

MH: What different parks did you work in? How did they compare? Do you have a favourite? 0607:

GI: There are special places and memories from Jasper simply because that’s where I first started working. Pacific Rim National Park at the time, was relatively new and the work of their Seasonal Wardens was very basic. It was “Don’t allow anyone to camp overnight on Long Beach”. It wasn’t technically a National Park but a National Park Reserve, which a big chunk of it is still even today. And so that was very much Law Enforcement oriented. But there’s something so special about it that virtually all staff that went there but might have gone,” Oh, I’d rather be in the Mountain Parks, climbing and working with horses, lots of wildlife work” quickly changed their tune. Everyone I know that went out there ended up loving it so much that they were sad or disappointed to actually leave. So Pacific Rim, again, really special place. But it’s hard to narrow it down because I also had a great summer as a Park Naturalist in Yoho National Park, and then of course, spent quite a few years at Lake Louise. I’d have to say the Lake Louise region would be my all-time favorite.

MH: What were some of your main responsibilities over the years? 0749:

GI: Like a lot of Wardens at that time, starting off as a Seasonal and then moving into a full time Warden, it was very much a generalist role. The classic example would be, for the summers in Lake Louise, the permanent wardens would have one seasonal warden working with them, and there was a team who was responsible for firefighting, a team responsible primarily for human wildlife interaction, and another team primarily responsible for Law Enforcement. So right there, there was Resource Management, Law Enforcement, and then Public Safety, and there was a Public Safety Specialist as well. I think a lot of the staff that were attracted to the job in those days were attracted to that great variety that you would get in the course of a year, and in some cases, even in the span of a single day. I know Lake Louise was very busy at that time with human wildlife interaction primarily with bears because it was just before the start of the bear proof containers for garbage. So there was a lot of bear activity in the village and particularly up at the Chateau Lake Louise. So you could easily be involved in a mountain rescue, a bear immobilization and relocation and some Law Enforcement work all in an eight-hour shift, and I think a lot of people were attracted to the job for that very reason. I mean, other people didn’t like it so much, but a lot of people really did. As Assistant Chief Park Warden in Lake Louise, Mike McKnight at that time said, “People who liked to work in Lake Louise tended to be adrenaline junkies.” I think there’s a lot of truth to that. So anyways, it was the generalist responsibilities for many years. I think it was probably my fourth year in Lake Louise, I applied for and became the Frontcountry Supervisor for Lake Louise region (North Banff Park) and did that until 1988 when I transferred to Banff and was the Backcountry Supervisor for several years. Then with re-organization, that role and the same position in Lake Louise were amalgamated as part of the “Program Review One, that basically downsized a lot of the staff. I then became Assistant Chief Park Warden for Frontcountry Operations based out of Banff for all of Banff National Park. The next “Program Review” split Banff Park into two sections, so I returned to Lake Louise as the Public Safety Manager for the last 10 years in my career. This started in Lake Louise and then when Tim Auger retired, they amalgamated those two positions together, so the position covered all of Banff Yoho and Kootenay National Parks. So yeah, quite a range of stuff between Frontcountry, Backcountry and Public Safety. Definitely, the greatest portion of my career would have been in Public Safety.

MH: What did you like / Dislike about being a warden? 1141:

GI: Well, I think definitely the variety. It’s like, no two days were exactly the same. There’d be a lot of similarities but there was a great variety, and being part of a much larger team that was like minded that way. So there were quite a few staff that really liked that variety and had no real desire to become a specialist, and then enough other people that wanted to become specialists. So, it just came down to the variety of the job. It was awesome!

Dislikes: Well, as most civil servants would say, probably the bureaucracy and some of the really inane things that would come up. And I think it still exists to this day. From Regional Office, but certainly headquarters in Ottawa, there was never a good system adopted or devised, or perhaps even looked into, as to how senior management could have a better understanding of what was actually going on in the Parks. And of course, at higher levels, it’s very understandable that they’re dealing with broad scale issues, not the day-to-day nuts and bolts. But they would then make decisions that would make no sense at the field level. So probably the most unlikable thing about it is that. And that kind of divide between senior management and field level managers or staff just continued to get wider and wider as years went on. A good example of that would be when I was a Park Naturalist in Jasper, the Superintendent would invite all of the seasonal naturalists and all the seasonal wardens separately to his house for a barbecue just to get to know those staff. The Superintendent felt very strongly about frontline staff being the most important part of the Park management and the Park experience for visitors. You would know that he and his wife would be out several nights a week to attend every Park Naturalist evening program. And you would just never know when, but he was keenly interested right down to the field level of what was going on. And then you fast forward to today, and I’m not so sure that that happens at all. I certainly know that there’s not much summer Naturalist programming anymore. And even for the Warden Service, the Warden Service has become so small and everything has been broken up into small little cubicles, with specialists working there. Senior Management likes that because they know they go to this person or this phone number to get that particular information. But by the same token, the divide between Senior Management and field operations has never been wider than what it is today.

MH: What were some of your more memorable events as a Warden? 1537:

GI: I think a really big one was during the centennial (1985) year. I was Frontcountry Supervisor that year, and His Royal Highness Prince Philip was invited to the dedication events for World Heritage Sites at the centennial. I was picked along with a number of other Wardens from Banff, to be his color escort. We actually got to know him really well, I would say, as well as anyone can as part of their royal entourage. It turned out he was a very, very smart guy, really interested in wildland conservation and we could tell that he was very well prepared. And one story on that, because I was the supervisor, I was attending these meetings with the advanced party, and one of the guys that we liked to call the protocol droid (Star Wars reference), who was rather humorless and was explaining how you’re supposed to behave with Prince Phillip, what to do and what not to do. And so I asked him, “Well, what if Prince Phillip asks one of us a question, what do we do?” And he says, “Well, he won’t ask you any questions.” Just in case I ask, what if? He says, “Okay, well, he will ask the questions, you don’t ask the questions. And you answer the question, and you end it with “your royal highness”. “Okay, I’ll pass that along”. “So, what if he asks another question?” “Well he won’t”. Just in case, I ask. The fellow said, “If he asks any follow up questions, then you answer the question and just finish with sir.” Okay, good. So, in comparison to what we were told to expect, what Prince Phillip was really like, he was absolutely charming, very well prepared, and absolutely interested in everything that the Parks were doing, what the Park Wardens did, what our roles were, and even questions about our personal lives – so completely different from what the protocol staff had advised us would happen.

I think another one was the Three Sisters hearings, for the land development around Canmore on the East boundaries of Banff National Park. At that time, I was actually the Backcountry Supervisor in Banff, but had knee surgery and so I was approached to coordinate Parks Canada’s response to it, and then that expanded to become federal Department of Environment response to it. We had a great group of people working on that (Parks Canada/Environment Canada intervenor presentation), and then I attended all the hearings for the full six weeks that they were being held in Canmore. It was really like taking a Master’s or PhD course in natural sciences, because there were so many scientists from so many different fields presenting. That was fairly intimidating when I was giving the presentation as well. But I think it had a fairly lasting impact on not just the management of Banff Park but of land management in general. Those battles are still going on today, because of course, every new wave of citizens in the Bow Valley have a harder time understanding what has gone on before. And a lot of people just see, well, there’s all this land around Canmore so why can’t we develop it, and what’s a wildlife corridor and why is it so wide; We should make it narrower because we can build more houses on it. So those sorts of fights continue to this day but I think that was a real turning point where for the first time Parks Canada had voiced an opinion at a public tribunal about development outside of National Park Boundaries. There were several high-ranking Parks Canada officials at the time that were very opposed to that. And of course, there was obviously some high-ranking Parks Canada officials who were very supportive of that. So, in my mind, it was kind of a seminal moment in Parks where Parks Canada at this point will now say what they feel is necessary for management practices outside of National Park boundaries. Not always successful, but yeah, it was fairly important.

MH: Can you tell me about any rescue/wildlife stories that stick out in your memory? 2145:

GI: I mean as far as rescues and wildlife stories, that’s kind of endless. I’d say lots of ink has been spilled about rescues.

One of the rescues I was on, on Mount Robson, which was significant. But other people have told that story. I mean, everybody that was involved on any rescue, Mount Robson included, would see it from a different perspective. And so everybody’s story would vary slightly, which is to be expected. But the real outcome for me was, was on the way down; but first back it up a bit – Clair Israelson, Marc Ledwidge and I eventually made it to the top and spent the night. It was a multi-day rescue. And then the next day, we were able to get the climbers that were stranded on the north face back up to the summit. We then started down but they were too weak and the weather was crumby anyways. So we ended up finding a great bivouac in a bergschrund not far below the summit that had snowed over and had a good snow ledge in it, all completely out of the storm that was raging outside. Then just as we got settled in, being closest to the snow hole entrance I heard the helicopter. A window had opened in the weather and we were able to get the rescued climbers slung out and then the pilot, Todd McCready, told us he only had enough fuel for one trip all the way to the bottom. Marc was the junior rescuer at that point so he went out and Clair and I stayed up top. In the rush to get everybody out, one of the rescued climbers I suspect, happened to grab my crampons as they were getting ready to go. The next morning, we were about to go and I’m looking around for my crampons and sure enough, they’re gone. The guys at rescue base confirm they’re down at the highway. So, then it became tricky for me to get down – it wasn’t so bad on all the snow up high but then when we got lower down there was verglas, which is a very thin coating of invisible ice over top of all the rocks. Clair and I soon linked up with another couple of guys, Gerry Israelson and John Niddrie, who were working their way up. We were roped up together and I’m in the middle, but we came into this real tight slot like canyon on the Schwartz Ledges and the physics of the rope work (“U” shaped traverse on snow covered verglas on rock) just didn’t work out. There were no anchors available, no way to belay, so if I had fallen, then I would have pulled everybody off. But the sense of teamwork there and the guys there, they were prepared to stay tied in and take the consequences. So, I made the decision that I would unrope and get through by myself. But that sense of team and potential sacrifice is something I think was a real hallmark of the Warden Service. When the chips were down, you could count that somebody was gonna be there with you and help out. So that, I think is very telling. It is something senior management never understood.

Oh, and the other stories, I mean, there’s lots of humorous ones, there’s lots of really sad ones. Wildlife work, I mean, when I first started in Lake Louise from 1978-1982, during the summer, bear management was kind of the overwhelming activity. And it was just at the start of what we now consider to be the bear proof, hydraulic garbage bins. We had just installed the giant transfer bins in Lake Louise, but we had not put the wall around it yet to keep the bears out of there. So sure enough, a sow grizzly with two cubs got in there and somehow, one of the cubs got into the gigantic transfer bin. Not the ones you see on the side of the street, but the big ones that are kind of out of public view. The sow was frantic about this. So, we set a trap in there, just to see if she would go into it, and fortunately she did, so we didn’t have to immobilize her, but the other cub is still running around but we thought we would deal with that later. So, then we were trying to get the cub in the bin out, we tranquilized the cub, but we wanted to go light on the doses because we weren’t really sure how much the cub weighed. This is all happening at one o’clock in the morning. What we did then is I got tied into a climbing harness and a rope and got lowered down into this bin to hook the bear up to a harness to get pulled out. But just in case the cub came to, the rope that I was tied to was attached to a pulley and then tied to the truck. And the plan was “Okay, we’ll just pull you out by the truck”. It was all kinds of goofy crazy things like this that were just kind of being invented on the fly. It was the start of a much greater program that resulted in being very effective. The whole garbage management program was very effective, but there was a period there that it was just crazy wild, seat of your pants sort of things going on.

28:33

But you know, back in those days, certainly Jasper, their backcountry wardens were doing 24-day solo trips, on horseback. Banff patrols were shorter just because the districts are smaller. Things like that today, people would probably look on with horror, like, oh, my gosh, how could that happen? It worked very well. There was sadly a fatality, but that actual incident probably wouldn’t have been prevented, (unless people were on two person patrols all the time and radio communications were 100% reliable everywhere). So, it perhaps could have been prevented, but by the same token, it allowed a system where people could work independently and relatively safely. Neil Colgan’s fatality is what I’m referring to. He got kicked in the back by his horse and died, probably a half day ride from Cyclone cabin.

There was a poaching incident on the east boundary of Banff National Park up Indianhead Creek, Terry Skjonsberg and I were on boundary patrol that time. We came across a kill site where a bighorn sheep had been taken inside the Park, we found the day bed, the butcher site and eventually found the shell casing. Of course, communication wasn’t that great in those days. The radio we had at the tent camp wasn’t able to get out so we were riding out that night, down a fairly steep mountain trail, covered in snow and ice, pitch black, overcast, no moon and just kind of riding low on our horses to avoid the tree branches that we knew were there to get down to the Indianhead Cabin and get communications. And again, it was a sense of teamwork and trust in one another’s abilities with the horses and riding skills but today would be considered fairly dangerous. But because of our knowledge of the horses, of the terrain of one another, and faith in one another skills, we felt that it was imperative that we do it so that we could get additional resources out to finish the investigation and then pursue the poachers. It’s events like that, that do stand out in your mind. You know, what a tight bond there was between the Warden Staff.

MH: How did the Warden Service change over the years? 3211:

GI: Just after the Second World War, it was very much a district system where Wardens and their families lived in the backcountry, some obviously in frontcountry as well. Centralization happened just before I started. A lot of the older Wardens were still coming to terms with that because it was a really significant change to the work that they were expected to do. It was a major social, physical, psychological change for them. But in my career, when I was a seasonal Warden in Jasper, so this would have been in 1976, was also when affirmative action was kicking off. One great story from then, I was a District Warden in Jasper so doing the 24 day solo trips, on the southeast Boundary, Rocky District, and it had been the kind of standard procedures for many years that the Tonquin Valley Warden, come hunting season, would close up Tonquin Valley and come and partner up with the South Boundary Wardens, particularly the Rocky District Warden, for the poaching patrols. The Tonquin Valley Warden that summer, just happened to be one of the first women who worked for the Warden Service, Bette Beswick. I came in to town at the end of one shift and was called into my supervisor’s office. (I was thinking, what’s going on here?) And then he asked me to close the door and I thought I was in so much trouble, but didn’t know what I’d done. He was just kind of beating around the bush, so he finally came out with the poaching patrol scenario in the fall. He advised me that the Tonquin Warden is Bette Beswick. And he wanted to make sure I was okay with that. What my supervisor didn’t know was that Betty was actually a really good friend of my then girlfriend, and I knew Betty really well. But a co-ed patrol then was a big deal. Older wardens flat out refused. We had an escort at the beginning of our shift with one of the Senior Wardens. Betty and I both thought that this was quite comical. We didn’t see it as a big issue. The Warden Management at that time saw this as a big deal. So anyways, it all worked out well.

And then I’d say the next big change probably came about in mid-1980s when specialization really started to come in, particularly for fire, aquatics, wildlife. So, it was a big change there. Prior to that, it would be in a rotation of the generalist Warden model. You might be the fire specialist for maybe two years, and then you’d be rotated and you’d be the Law Enforcement Specialist and that sort of thing. It was around the mid to late 1980s when those positions were made permanent, that you would apply for that particular role and that would be your career choice, basically. And what was really good about that was that those programs really took off. It didn’t matter whether it was public safety, wildlife management, fire management, aquatics management, all of those programs really took off and expanded. And of course, that just collided headfirst into the “Program Reviews” in the 1990s, which basically started cutting staff and cutting budgets. So, there was really a number of golden years, maybe even a golden decade (or two) in there, the 1970’s, 1980s and part of the 90s, where the level of professionalism in Parks Canada really had radically improved. And then of course, that all changed in the early 2000s, where now the Warden Services is strictly Law Enforcement and all these other specializations are their own cost centers. And, again, I retired just as that was happening so I haven’t really seen what the impact is, but certainly what I hear is that staff don’t talk to one another as much as they did. Certainly, at work, a wildlife specialist does not get involved with rescues or law enforcement and vice versa. So the generalist role is basically gone in the bigger Parks but I suspect it still is happening (to some degree) in the smaller Parks simply because they don’t have the staff to have enough specialists in everything. Those are the big changes the way I saw it.

MH: What about the Warden Service was important to you? 3849:

GI: Certainly, the biggest idea is protecting and preserving National Parks and the ecosystems within and adjacent to National Parks. The “keeping people safe” aspect, I think comes out of that. Certainly, some of the more remote parks that I had really great pleasure and honor of visiting as part of my role as Public Safety Specialist it is. Seeing parks where there weren’t that many people, particularly northern parks, visiting those parks the public safety aspect was a component, but it certainly wasn’t such a high profile as it is in the Western Mountain Park. But everywhere that the concept of protecting and preserving landscapes in my mind was always the most important.

MH: Are there any legendary characters or stories associated with the Warden Service that you can share? Is there anyone from the Service that stands out in your mind? 4009:

GI: I mean, there certainly is no end to larger-than-life characters. And I’m sure lots of people would probably settle on maybe some of the same names, but I tend to think of some of the people that maybe weren’t as high profile but still did just an outstanding job. I look at people like Cliff White and Ian Pengelly, how they really persevered in getting our Fire Management into the modern era and even becoming a model for other land management agencies. And Charlie Pacas, his work in Aquatics Management, something that a lot of parks staff undervalued but he was certainly one of the essential people to get that highlight. Even today, I believe it’s still a bit of a struggle. I mean, it takes a serious incident for parks to get engaged with that. Thinking in particular, like Whirling Disease (a parasitic disease affecting Rainbow trout, cutthroat trout and other species), that’s a big deal. But the day-to-day stuff, there Charlie was very pure, I believe, in wanting to get invasive species out of the backcountry waters of the Park and he faced a lot of trials getting that program going. I think a lot of the larger-than-life characters get talked about a lot. But I think a lot of it is people that weren’t that high profile is what in hindsight stood out for me. The people that kept things working when everything was kind of against it. And that’s not just within the Warden Service but even trail crews in the Park, Don Gorrie has been at it for a long time. And like all of us, he’s got pros and cons, but man, he has kept the trails program going and faced a lot of financial adversity. So in my mind, what should be the legendary characters are the people that actually kept the lights on, so to speak. When some other people were bright shining stars and larger than life characters that in the end, a lot of that stuff didn’t have that great an impact compared to the consistent performance of other staff.

Charlie Pacas,Acquatics Management

MH: Is there anything about the Warden Service, as you knew it, that you would like future generations to know? 4314:

GI: Yes, you can have generalists. And generalists that can operate at quite a high level in a very wide range of skills. There seems to be a belief that, and certainly a lot of that came out of Ottawa, there’s no way somebody can be doing (the work with) all those skills. And, indeed, when it finally ended, it was to the point where nobody could do all of it, but they could do several of those things. And I really do think the organization has done itself a disservice by trying to specialize absolutely every position, because the Warden Service had adapted, year after year, decade after decade, to the new challenges over a wide variety of the entire country. And they did it by being generalists in a very great sense, and I would think that the future generations should reexamine that, then Parks Management might actually be better off than what it is. Not to full generalization obviously, you need the specialists, (and the range of generalist might be smaller) but there are staff now that are underutilized at certain times of the year within their specialization. One of the great things from before is that say, for example, front country staff that are desperately needed staff during the peak tourist months, aren’t needed when that visitation tapers off. If you have that same number of staff, it makes no sense. But that just happened to coincide with the fall hunting season on the park boundaries. And so that work would happen, and then that morphed into the winter avalanche control and avalanche forecasting season. So you definitely could utilize staff better that way rather than having people specialized and unable to then assist other parts of the park operation.

MH: What made the Warden Service such a unique organization? 4603:

GI: Well, on the surface of it, it would be the fact that it was generalized, that it had many different roles that worked for the operation and management of the park. But that’s in a very broad sense, I think the uniqueness of it was that it was able to attract the people that it needed to do those jobs. I know there was a period when people thought “Who would want to be a Park Warden out on backcountry poaching patrol if they’ve got a science degree?” We will never get people to do that.” Well, yeah in fact you will, and we did, (I’m one of them) even people with master’s degrees that wanted to do that. I think the fact that there were multiple roles that you could work at was what attracted a lot of people and you’d see this year after year after year, the number of applications coming in for seasonal Warden jobs, staggering numbers of people applying for that. I think that’s something (a concept) that has been lost and I don’t know if it could ever be regained. But that you can get unique as well as generalist people, personalities, skills, education levels all coming in together and then working together I guess is a very special or was a very special place to work.

MH: Do you have any lasting memories as a Warden? favorite park cabin horses trails humorous stories.

GI: 47:56

Favorite Park I would still say Banff would probably still be my favorite. Favorite region within that would be the backcountry of Banff, which is really unique. Jasper is a huge backcountry. A lot of it is like big, broad valleys, whereas Banff is more rolling close to the alpine, a lot of trails above treeline, so yeah, it’s fabulous. And then having become a mountain guide as part of my public safety work, and being stationed in the Lake Louise area, there can’t be any better place as far as I’m concerned on the planet. Favorite cabin that’s a tough one: Scotch Camp for a Banff Warden has probably a lot of great memories, humorous stories, sad stories – all kinds of stuff at Scotch Camp. Palliser cabin is a pretty unique location. And then as far as horses that would have to be my horse when I was Backcountry Manager, Whisky. I started off with him as a three-year-old right up until he had to put down because of a broken leg when he got kicked by one of the horses in the pasture. But he was a great horse.

MH: Do you ever miss being a Warden?

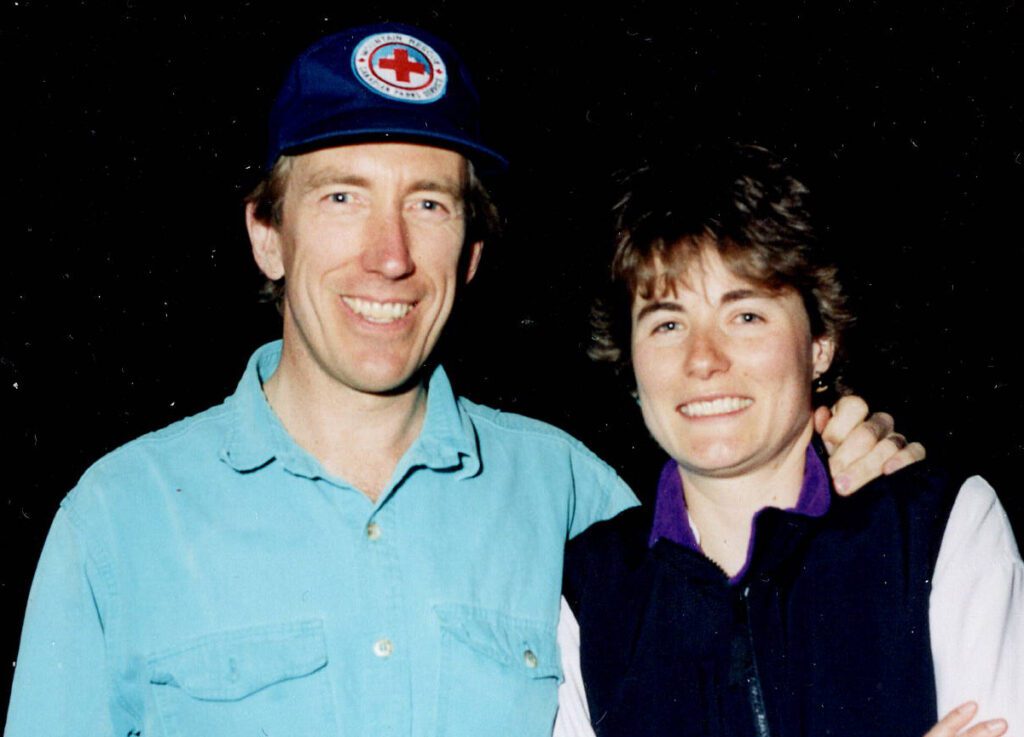

GI: Sometimes, but I’ve been really busy. Marie-Pierre and I have been trying to do a lot to traveling and I’ve kept doing some work, mostly guiding related work since I retired. There’re parts of it that I missed, but overall, I had a great career. I was a warden for 33 years and another seven summers as a seasonal something with Parks. So that was lots of time.

Gord and Marie-Pierre

MH: Do you have any photos of yourself as a warden that you would like to donate? Artifacts?

GI: Yeah, I will have to go through them some more and just see. Certainly, any print photos, I’ve got a scanner so I can scan those. And then artifacts memorabilia. You probably already got stuff. I’ve got some old Hanwag leather/plastic ski boots. Pretty sure the Whyte Museum already has some of those. I’ve got one of the old cotton anoraks and the old green knickers, got some of those someplace. I don’t know if they want that sort of stuff. Yeah, but I can ask if they want those items. Oh, I think I’ve got some of the old gun seals. It used to be that if someone was coming into the park, they would have to get their firearms sealed and I might have one of those.

MH: What year did you retire?

GI: February 2008 but was burning off leave after my birthday of 2007.

MH: What do you enjoy doing in retirement?

Marie-Pierre and I have been able to travel a fair bit to places around the world. And we started backpacking again. She’s obviously still quite busy with her fire research work. And I’ve been fairly busy with doing some guiding work mostly training military groups. So yeah, it just seems like we are keeping busy and mostly healthy.

MH: Is there anything I haven’t asked you that you think I should know about the Warden Service?

GI: I think it was covered very well

MH: Anyone else to interview?

GI: Bill Moffatt, lives in Victoria BC and was a Seasonal Warden in both Jasper and Lake Louise.

Bette Beswick would be great to talk to. She started off as a Warden and then worked at Regional Office for years. In my mind she’s one of those unsung heroes. I mean, she was one of the very first women in the Warden Service, so very capable and competent. But you know, just quietly doing a great job.

MH: Any final comments? Don’t think so.

Monique Hunkeler first started working with Parks Canada in 1989 as Secretary to Banff National Park Finance Manager. She moved into a position as Dispatcher for the Banff Park Warden Service and later worked within Banff National Park and Town of Banff’s IT departments. She is experienced with the interviewing, transcription and archiving process the Park Warden Service Alumni Society.