This Oral History interview was funded in part by a research grant received in 2022 from the Government of Alberta.

Park Warden Oral History Project – 2022

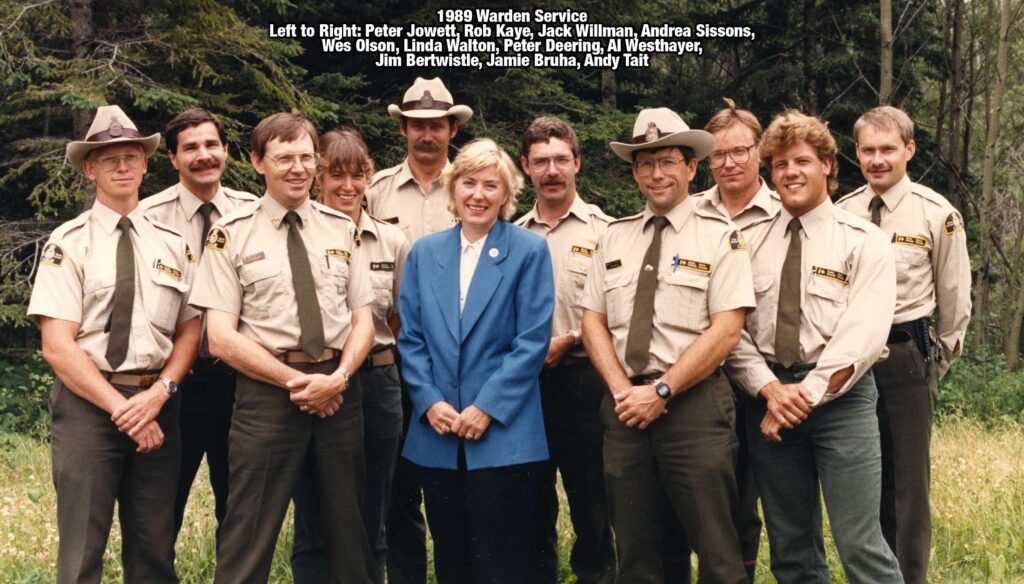

Phase 12 – General Questions – Alan Westhaver

Working in Canada’s National Parks and being a National Park Warden between 1974 and 2012 was like having a dozen different careers all rolled into one, having one foot in the past and another on the leading edge. And, all the while, being challenged to find ways of ensuring that some of our country’s great ecosystems were protected, restored and, not quite, enjoyed to death by Canadians. What a privilege it has been to explore, work, live and raise our family in such wonderful places

This is a sample of outstanding events which helped shape the path of my Warden career. However, the true highlights were the wide array of deeply dedicated and talented people that I worked with.

Place and date of birth?

I was born in Calgary, Alberta in July, 1954 into a family that had lived and toiled near, Fort McLeod, in the foothills of southern Alberta since before 1900. They were pioneers; their first house was built of prairie sod.

Where did you grow up?

My sister and I grew up in the SW and NW sectors of the City of Calgary but most of my childhood memories are of times spent in the foothills and mountains or on lakes of southwestern Alberta and southern BC. As a youngster I observed my grandfather’s close relationship with the land. He was a farmer and rancher; but it wasn’t until our walks in the fields during my teens that I began to understand and appreciate that attraction.

How did you become involved in the Warden Service?

My connection to the Warden Service, and my eventual career was mostly the result of chance meetings with kindred souls who influenced my path through life, beginning at a very early age.

I think these interview questions were really effective in getting me to examine my roots and how I felt about my career. So I have a new respect for this Warden history project. One of the thoughts that prevails is that none of my family worked for the government but they were very, very strong in that sense of building community (even schools) and service to others. And so that’s a big part of my family heritage. And I think that’s core to my attraction to and why I stuck with the Warden Service – because I believe deep in my heart that National Parks are a public service, and they’re a really important part of our national identity. So there’s an attraction there, we were doing things as Wardens and Park Managers that were much bigger than just a job.

Although living in Calgary, my parents and many of their friends had small-town or farming roots. They were avid fishers with a love for the outdoors, and that translated into memorable car-camping trips. The highlights were multi-day fishing father/son adventures into remote corners of the (then undeveloped) Kananaskis, Highwood and Elk River watersheds. We travelled barely passable forestry or power line trails by car, then by foot and sometimes with our gear piled “pack-horse” style on top of an old army surplus jeep and push-pulling it into remote areas. In winter, we explored by ski-doo into remote lakes and streams. Truth be known, I spent most of my time poking about in nearby woods and slopes, while my Dad fished. At times, I’d spend the day on cross-country skis, sometimes arriving at the fishing destination just in time to get towed back out by snowmobile. In planning these trips, I remember being curious about the big green or white blank patches on some maps, and scattered along the continental divide between Alberta and British Columbia. Of course, those were National Parks. Several small campgrounds in Banff were easy family destinations for summer camping in the 1960’s and early ‘70s. In winter, we made annual family ski-doo trips staying overnight at Num-Ti-Jah lodge. I have special memories of my parents chatting with the legendary Jimmy Simpson Sr.

Boy Scouts was another major influence that drew me toward the Warden Service. I joined Cubs at age 6, then progressed through Scouts, Ventures and Rovers with the 4th Elks Tri-wood troop. A core group of my buddies and I were fortunate to be mentored by exceptional volunteer leaders with a knack for creating enthusiasm and adventure. They were outdoors people with deep knowledge and love of nature. Consequently, throughout my teens I was fortunate to spend 2 or 3 weekends per month, year-round, travelling or camping (under canvas or a sheet of plastic) in mountain terrain. Through Scouting I was introduced to and became proficient in many skills core to the Warden job.

Thanks to a $10 annual membership and a pre-dawn “shuttle” by my father, I could also show up on weekend days at the Calgary “Hostel Shop” at 0500 and take advantage of carpooling to join epic day-trip adventures onto Banff National Park, Kananaskis trails with other avid X-C skiers. We rarely returned to before 7 p.m., which resulted in occasional school-desk naps on Mondays.

At the age of 16 my first Scouting buddy got a car. That extra degree of freedom led directly to a fortuitous encounter with a National Park Warden, an event which changed the direction of my life. Five of us crammed our gear into a beaten-up Chev sedan and headed for Banff. Arriving at the Sunshine parking lot, we backpacked into the Egypt Lake area for 5 days in August, I think it was 1970. We were fit and keen, but most of our gear came cheap – from Army Surplus. As we topped the height of land I recall shouting “Healy Pass, what a pain in the Ass” as the shoulder straps of my overladen Trapper Nelson pack cut a little deeper and a 14” cast-iron frying pan swung from it. We had glorious weather and, based at the Eqypt Lake Shelter, hiked to Redearth and Whistling Passes to fish all the local lakes and streams. The heavy frying pan paid good dividends, we sure ate well!

By mere chance I met Seasonal Park Warden, Julian Richaud, during one of our day-trips. Our crew was exploring the outflow stream of Scarab Lake and watching trout near the point where it cascades down to Egypt Lake. To our great surprise, there was a person clearing debris from a coarse metal screen set into the stream. He was friendly, sharply uniformed and impressively articulated the reasons for his work. As I left Julian I was “I wonder how I could get a job like this? It seems like a good fit for the things that I value.” That random wilderness encounter altered the course of my life.

Finally, choosing the University of Montana prepared me well to be a Park Warden. Missoula was also a regional headquarters for the US Forest Service, and home to federal research labs engaged in wildlife, fire and wilderness recreation. The forestry and wildlife faculties were at the center of national controversies about National Park management issues, and it had a cadre of Americas best professors. I took full advantage of those opportunities.

3a. Which national park did you start working in?

I worked in National Parks for parts of 4 years as a biology technician before joining the Warden Service. My first employment was in Yoho, summer of 1974. It came as a stroke of luck due to a tip from one of my Northern Alberta Institute of Technology instructors in the Forestry Program. Consequently, I was hired as a field technician by Dr. Peter Kuchar, a plant ecologist and an accomplished botanist, to survey, document and map forest/vegetation types of the park. Our data was combined with results from concurrent soil surveys to create a baseline for future resource management decisions within the park. Our 5-person team included Seasonal Warden Gord Antoniuk; Gord Rutherford was attached to the soils team. Over the next 4 months, fellow technician Jim Tutt and I hiked and bush-wacked the length of every Yoho’s watershed (except the upper Ice River), traversing repeatedly from valley-bottom to alpine elevations. We were required to recognize and name all species, from mosses to trees. The days were long, and many evenings spent keying and pressing plants. However, I was learning from an expert scientist and living at the Boulder Creek bunkhouse. I spent mealtimes and recreational time with park staff and Wardens (like Tim Auger, Gord Rutherford, Julian Richaud, Dale Portman, Darro Stinson, Bill McDonald and Chief Park Warden Hal Shepherd. They provided insights and inspiration about aspects of the Warden role and, on multiple occasions I joined them after-hours on incidents when extra support was required for chainsaw or Pulaski duties. By mid-summer, I was hooked on National Parks and the idea of attaining a Park Warden job. Those experiences and people influenced my educational path too.

Because of my experience in Yoho, I was hired upon graduation from NAIT Bio-Science program the following spring to work full-time as a Vegetation Technician with a team led by the Canadian Forest Service, Canadian Wildlife Service and University of Alberta. The project was to conduct an Ecological Land Classification System (Biophysical Inventory) for Banff and Jasper National Parks. Over the next three field seasons I lived with the Banff crew at the Eisenhower (Castle) Junction Canadian Forest Service camp and at Saskatchewan River Crossing. On average, I hiked or back-packed 1600+ kilometers each summer through every nook and cranny of most Banff watersheds. In travelling in the company of ecologists and scientists like Peter Achuff, Gerry Coen, B.D. Walker and John Stellfox, I was gifted a priceless education of insights into Rocky Mountain ecosystems that I drew upon throughout my career. At the same time, I continued to befriend park staff and to observe the backcountry, law enforcement and public safety duties of the Warden Service.

While working for the Canadian Forest Service and in living in Parks, I met numerous graduates and students from the University of Montana, including Cliff White and Terry Skjonsberg. Collectively, they influenced me to continue my formal education and, by 1980 I had earned separate B.Sc. degrees in Wildlife Biology and Forestry (Range Management) by 1980 between work stints in Banff. Outside my majors, I took as many under/post graduate level courses in wildland recreation and national park management as were available. Good fortune continued to follow, as many of my instructors at University of Montana were renowned experts with key involvements in controversial issues in US National Parks like Yellowstone and Glacier (USA); issues that inevitably brewed up in Canadian parks as time went on. Ron Leblanc was attending the University of Montana at the same time. In fact, he was the first guy I met. He leaned out a dorm window when I pulled into the parking lot and yelled, “Hey! You want a hand unloading your car?” We became best buddies down there, and for a lot of years later on because we crossed paths often in our careers.

3b. My first job as a Park Warden was in the summer of 1978, when I was hired as a Term Park Warden in Elk Island National Park, a position that lasted from May until I returned to the University of Montana in September. It was a full-on introduction to worlds of visitor management/law enforcement, travel by horseback, intensive wildlife management, bison and the treasure-trove of wisdom held by veteran Park Wardens (and their spouses) like Fred (Ann) Dixon, Bill (Cheryl) Walburger and Jack (Shirley) Willman. Elk Island National Park also opened my eyes to the fact that National Parks encompassed many amazing ecosystems – beyond the mountains. Coincidentally, that summer I also met and fell in love with the “girl next door”, a wonderfully cute and intelligent Seasonal Park Interpreter named Lisa; my life partner ever since.

What made you want to join the Warden Service?

It was those experiences, the people I met in Parks, and a particularly influential University of Montana professor and ex-United States National Parks Service Biologist named Riley McClelland that cemented my feelings for the importance of National Parks ecosystems to Canadians and my desire to continue seeking a career in the Park Warden Service. I came to view Park Wardens as key implementers of actions required to preserve our National Park system, and to help other citizens to appreciate and care for them. I was also strongly attracted by the multi-disciplinary nature of Warden work and the wide diversity of challenges which demanded flexibility of outdoor knowledge and skills. It seemed to me to be a job that provided endless opportunities and challenges. Besides, I could not stand the thought of a desk job. This was a job where you had a chance to make a difference! There were a lot of issues that were important and on the charts that needed attention and I was lucky to be able to work in a number of those areas. Whether it was bears and garbage, educating backcountry visitors, fire management, ecosystem restoration, wilderness recreation management, invasive plants or fire protection for park communities there seemed were endless opportunities to learn and grow and change things for the better. Where else could you have an office that was measured in 1,000’s of square kilometers?

What different parks did you work in? How did they compare? Do you have a favorite?

I chose to work at many different levels, and in many different parks and regions of Parks Canada. I’ve never thought to compare parks; each one is unique in its own features, issues and culture and has had a different fascination for me. That’s the beauty of our system, and I ’m happy to have experienced that with our family.

Mainly out of curiosity about many ecosystems, which was shared later on by Lisa and our children, I was able to transition from early years in Yoho (1974) and Banff (1975-1977) into Term and Seasonal Warden positions in Elk Island (1978) and Banff (1979-80) and eventually to fulltime Warden positions in Banff (1980 – 1988), Elk lsland National Park (1988-1991) and Jasper (1996-2012). In between, I took on the positions of Regional Fire Management Officer for Prairie and Northern Region in Winnipeg (1991 – 1993), and as manager of the newly established Western Fire Management Centre in Calgary – with vegetation/fire responsibilities for all of western Canada 1993-1996). The latter two positions also gave me the opportunity to work at the National level, team up with park staff to work across agency boundaries with Provincial and Federal counterparts to address fire, vegetation and forest insect and disease issues in the National Parks and Historic sites in all three regions, across 4 provinces and 2 territories.

So when it comes to how parks compare, my perspective, and my wife’s too, was that every one of them is a different ecosystem and that’s by design in our system. And there are things to love and be in awe of in every one of those ecosystems. And when we went to Winnipeg, that really became obvious. We had an appreciation for Elk Island, for example. We weren’t just stuck on the mountains. But when we went to the Prairie and Northern region, I mean, those northern parks, grasslands, Riding Mountain, Prince Albert, I spent time in all of those places. And I guess I have an appreciation for all of those ecosystems. And just like today, we can go down to the desert and be totally enthralled by what there is to see and do there.

Banff and the Egypt Lake District will always be my sentimental favorites. But no question about it, Jasper is ‘home”, when it comes to family and friendships. Our youngest daughter was only about eight months old when we moved there, so yeah, all of our kids really still think of Jasper as home too. We still have a lot of friends and connections there. And fortunately, our youngest daughter Theresa lives there still with our granddaughter Aven. She is the Indigenous Relations Liaison Officer for Jasper National Park, and proudly connecting with her family heritage on Lisa’s side of the family tree.

What were some of your main responsibilities over the years?

I was extremely fortunate to have a career that spanned the full range of responsibilities which comprised the traditional “jack-of-all trades” Park Warden lifestyle, until it’s unfortunate demise in its centennial year. However, I did specialize in many aspects within the equally diverse worlds of natural resource management – with an emphasis on specializations related to vegetation and fire.

However, advancing our ability for sound, science-based natural resource management was always at the core of my passion for work; regardless of where I was stationed in front-country or backcountry positions, or assigned to varied Warden functions. My first seasonal Warden posting (1979) was at the isolated Saskatchewan River Crossing Warden station, on the Icefield Parkway, in Banff. It was a terrifically busy summer season, non-stop with fires, bears, motor vehicle accidents, medical emergencies, odd-ball visitors, back-country patrols, trails to clear, horses to keep, hunters and law-enforcement incidents. Support was far away, so fellow seasonal Tim Laboucane and I got to do it all… aided by our yellow rental half-ton (with a cherry on top). We had to continually pivot from one skill-set to another.