The following year, as a seasonal “Town” Warden in Banff, I was teamed with Monte Rose, as Assistant Bear Warden, at a time when garbage was freely available and bears roamed the townsite on a nightly basis. However, equal time on nightshifts was often spent on law enforcement patrols and attempting to keep peace in the campgrounds. Our days were peppered with frequent public safety occurrences, visitor/wildlife conflicts and a Disneyland array of other adventures. I was frequently tasked with preparing environmental assessments which brought me into contact with specialists at Western Regional Office, the business community and utility companies. The opportunities for learning were endless. Better still, the “Bobcat Logic” shared in the coffee room and hallways by veteran Wardens like John Wackerle, Perry Jacobson, Bill Vroom, Larry Gilmar and Earl Skjonsberg were priceless. New-school was merging imperceptibly with Old-school and it was a time for “earning my stripes”. In spring, 1980 I was hired as a permanent Warden but continued working closely in bear management and other front-country duties. There was a constant adrenaline rush of responding to urgent events in Canada’s busiest park, but my willingness to put pen to paper had been noticed. Gradually I was assigned to dig into more persistent resource management problems the park was confronted with, and that was to my liking as well.

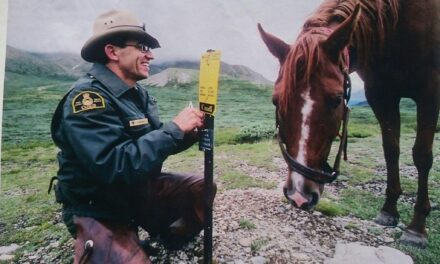

Eventually, I was assigned (for 3 winters and 2 summers) to backcountry duty and made responsible for the Egypt Lake Block. Due to the short summer season, I was assigned to spring bear and fall hunting season patrols on Banff’s east boundaries. Winter patrols took me on extended cross-country ski travel throughout the park. Along with Doug Harvey and Ian Pengelly, I worked with Western Regional Office staff in developing a backcountry zoning plan for the 4-Mountain Parks, and a backcountry management plan; we had branch offices in the Warden Office basement, and Egypt Lake and Windy Warden cabins. Similarly, I worked with Ron Hooper (WRO) and BC Parks to develop and implement the Sunshine Meadows Summer Use and Monitoring Plan. The good-natured wisdom of excellent managers like Assistant Chief Park Wardens Peter Whyte, Keith Everts, and Mike McKnight prevailed over all.

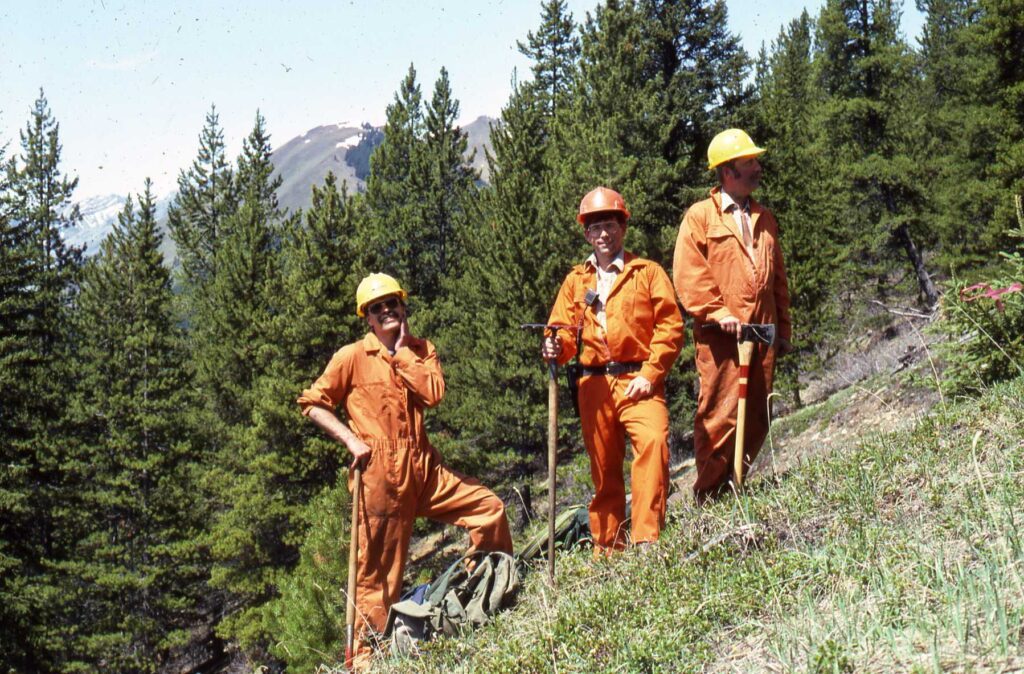

Thanks to Cliff White, the modern era of wildland fire management was beginning in Parks Canada. Being in Banff, I was quickly drawn into the earliest prescribed burns. In 1987/88 I took over the Banff Fire/Vegetation program when Cliff re-located temporarily to Ottawa to establish the national program.

During a 3-year return to Elk Island my role was to co-ordinate the resource management program, the focus of most Warden duties in the park, under the dynamic leadership of Chief Park Warden Jack Willman. It was a great adventure, since the park had a long history of collaboration and active research with biologists at the University of Alberta, C.W.S. and Alberta Fish and Wildlife. We were also blessed with keen staff (Peter Deering, Terry Winkler and Norm Cool among them) who already knew the ropes, and soon joined by hard-working recruits like Wes Olson (now a globally respected bison expert), Peter Jowett , A.L. Horton and Dennis Madsen. As a team, we initiated an aggressive prescribed burn program. Public safety and Law Enforcement occurrences were less frequent but also significant responsibilities. Unique to Elk Island National Park, we also maintained basic structural fire-fighting capabilities due to our rural setting. That gave me an advantage later on in my career, as I became heavily engaged with Municipal Fire Departments.

I count myself as being very fortunate to serve as the Regional Fire Manager, at a time that was really the birth of modern wildland fire management in parks, initiated by Cliffy White. I spent six years setting up and operationalizing the basic support systems necessary to implement “Keepers of the Flame” the new blueprint for fire management, and revised Park policies and directives. Those included financial and administrative systems, arranging crew mobilization and resource sharing with other Canadian agencies, firefighter training and maintaining our Fire Command Teams.

A highlight of those years was being able to create a consensus that among senior managers and Chief Wardens in Prairie/Northern and Western Regions to pool our limited resources in one place, and to start a “fire service center” in Calgary. So, we moved to Calgary, and I worked from there to get that off the ground. It accomplished lots of good things. In those times we had the advantage of “Green Plan” funding to augment our regular budgets, and were granted discretion to set collective priorities for allocating those funds towards critical research, equipment, training and operations. It was an exciting and very collegial time

Although there was an opportunity to go to Ottawa, following six years of living in big cities our family was all feeling the need to “get back to the real world” (if you don’t mind me calling it that), get our feet back on the ground, and to continue living in a “park” lifestyle. That is where Lisa and I wanted to raise our kids.

When, thanks to Paul Galbraith and Michel Audy, there was an opportunity to go to Jasper as the Park’s Vegetation and Fire Management Specialist, we jumped at the chance in August, 1996. I had a great partner there in Rick Kubian. At that time, there was also an opportunity to carry on with several initiatives I was already heavily involved in at the regional and national level, and a lot of collaboration amongst all of the Mountain Parks. Most parks had a fire management plan at that point, but it wasn’t connected to anything. Fire plans needed to be part of a more comprehensive vegetation management plan in each park, and Chief Park Wardens felt we also needed a common vegetation strategy among the Mountain Parks. I led that initiative, along with ecologist extraordinaire Peter Achuff. We had been a good team, working together in the Calgary office, and now both in Jasper. What a lucky guy I was to work with Peter and keep learning from him, we are kindred spirits. That was a big and important initiative based on common principles, and giving fire management plans a stronger base in fire history and ecology. We also created a non-native plant strategy for all parks.

Within a few years some really interesting things started happening in Jasper’s fire/vegetation world that caused it to expand greatly. There were three big aspects to that. First, the fact that the Trans-mountain oil pipeline through Jasper and Mount Robson Provincial Park was approved to be twinned (a massive and potentially controversial undertaking. Second, for many years, the mountain pine beetle had been flaring up sporadically, particularly in BC but with a few small outbreaks in the Mountain Parks. We knew that it was likely to move, in epidemic proportions, into Banff and Jasper. I had gotten very involved with the Mountain Pine Beetle issue at the regional level and co-chaired an Inter Provincial Committee, between BC, Alberta and Parks that we started up to deal with that and strategize together. Third, at the same time, we were trying to grow Jasper’s prescribe burn program, implement a complex network of forest fuel reduction around the townsite and major built-up areas of the park (to facilitate future prescribed burns and simplify wildfire control), and initiate restoration in dozens of large, festering disturbed areas and old gravel pits. As a result, we split my position into two positions, and hired Dave Smith to look after fire operations, and beetle stuff. I retained all other aspects of the vegetation/fire function, including the forest fuel modification and restoration project. Those were really busy and exciting years, but really demanding. Somehow, without taking leave, I managed to cram getting my M.Sc. degree at the U. of Calgary, into those years as well, by combining wildlife research into our forest fuel management program. Honestly, I am not sure how my family put up with me during that effort – but I am glad they did. Consequently, we call it the “Family Masters Degree”!

What did you like about being a warden?

Several things stand out to me as “things to like” about being in the Warden Service in those times:

The extraordinary breadth and variety of the job overall, as well as the wide range of challenges we faced each day.

The extraordinary cast of dedicated, talented and adaptable characters who were part of the Warden Service, not just Wardens, and the feeling we were that our work had national significance.

The very strong esprit de corps and pride taken by Park Wardens, and those who worked together inside the Warden Service (e.g., our indispensable admin support personnel, Seasonal Staff, Dispatchers, Trail Crew members and Barn Bosses and Horse Wranglers).

The comradery and teamwork that took place during emergencies and training schools between Wardens from across Canada and/or between local Wardens other functions within the Park. We had a lot of enjoyable times we had working together.

The opportunity to work closely with, and exchange ideas with such a wide array of professionals, from biologists and ecologists to law enforcement, search and rescue or wildland firefighters from other agencies, the private sector, educational institutions and countries.

7a. What didn’t you like about being a Warden?

The division, hard feelings and functional stove-piping that came about as the result of the hand-gun controversy, eventual break-up of the Warden Service and the inevitable decrease in National Parks ability and capacity to deal effectively with (and deliver) on all four functions of the traditional Warden Service (i.e., law enforcement, public safety, backcountry presence and natural resource management/ecological integrity/science). Those needs never went away and that was my greatest frustration.

What are some of the more memorable events of your Warden Service career?

More than events, I look back and realize that what I cherished most about the Warden Service were the innumerable, incredible individuals I was fortunate to have on my own staff. I think that Parks Canada was so blessed to have so many incredibly dedicated and capable people. As well, it’s important to me, to cite the exceptional leaders I worked for and was mentored by, like Chief Park Wardens Andy Anderson, Peter Whyte, Jack Willman, Paul Galbraith, Ray Frey, and Brian Wallace; Park Superintendents like Charlie Zinkan, Doug Stewart, Greg Fenton and Ron Hooper; and Regional Managers like Alan Masters, Ken East, Doug Hodgins, Doug Kerfoot, Don McMillan and Gail Harrison.

In response to the question though, I experienced innumerable memorable events during my Warden career. Some of them humbling:

Almost attaining the elusive “Warden Hat Trick” on several occasions by doing 3 out of 4: fighting a fire, writing an appearance notice, capturing a bear, or participating in a rescue, in the same day.

An almost “hat trick” came in my first summer at Saskatchewan River Crossing. Clair Israelson was head of public safety out of Lake Louise, and he organized a training school for a bunch of us down by Herbert Lake, the junction of Highway 93 and Trans Canada, where we did some rock climbing, and we also set up a big rope and pulley system that went right across Herbert lake. It was basically a zipline had been created right across from a high rock face, on one side of the lake down to the highway on the other. And so we had an extraordinarily great day of public safety training. And we were just packing up the ropes when the radio went and it was the dispatchers reporting a wildfire on Mt. Norquay. It started about two thirds of the way up the Norquay road. So we jumped into our trucks at the junction at Lake Louise and roared into town. And by this time, the fire was moving quickly. It was it was definitely the kind of weather where fire could move quickly. So there was a fire – kind of intermittent ground fire – burning its way up towards the Norquay ski hill. And we got to the top of that zigzag road (steep switchbacks) and there was wardens everywhere. And there we were in our knickers and wool socks, the whole public safety gang in that mentality, and in there we were. That’s where I met guys like John Wackerle and Larry Gilmar, a whole bunch of guys and cowboy boots and a whole bunch of guys in shirts. And, you know, there was a major fire setup going on. And by nightfall, we had that fire out and under control and pretty well out. But we’d already put in a really, really long day. I drove from Saskatchewan Crossing, we had the rescue practice and then onto a fire. And in there we were all sitting at the top of Norquay eating Kentucky Fried Chicken that Peter Whyte had arranged for us with the whole Banff crew. Every one of those people, despite their background, grabbed onto fire pumps and hoses and just went to work and it was seamless. And so there we had two of the big three in one day. Wow. But that was a really taught me a lot about who wardens were and what they could do and how adaptable they were, and in how they could switch from one thing to another and be really good. And that was impressive.

While on boundary patrol October 30th, on the back of a windswept ridge in sheep country, being caught in a slab avalanche, sliding down a steep-sloped gully towards a cliff band, with the avalanche dog at my side, looking up at Scott Ward standing on the upside of the fracture line.

Seeing Randall Schwanke’s eyes widen into saucers, as we lifted off the Waterton heli-pad, during the Sofa Mountain wildfire (1998), into a 35 km/hr west wind, and he spotted a NEW column of black smoke and flames erupting from the public campground, with nothing but bone dry grass as far east as you could see.

Tackling a young-of-year grizzly cub in a sparsely gladded alpine meadow, at an illegal camp near Bourgeau Lake (Banff National Park), hoping to free it from a massive tangle of parachute cord, as pilot Jim Davies maneuvered above hazing off the angry mama bear, and Dave Cardinal stood guard with shotgun in hand, then discovering the cub was fatally injured from its overnight struggles.

Hearing three shots ring out at exactly 0747 hours in the morning, when the infamous “Black Grizzly of Whiskey Creek” was shot, after being ensnared, thereby culminating a month-long series of bear attacks that took place on the edge of Banff townsite in 1980.

As the junior bear warden in Banff townsite that summer, it was my second year as understudy to Monty Rose. That was my second year and townsite and so it was the second year of bear handling. Because of the series of maulings near Whiskey Creek, it seemed like I was getting home at 11 o’clock or midnight, and leaving at five in the morning for the entire summer. At that time, we were living at the old Spray 8-mile Warden Station. It had been taken out of moth balls, because there was no place else for Lisa and I to live. A ton of stories came out of that event, and Sid Marty did a wonderful job of writing about it in “The Black Grizzly of Whiskey Creek”. Peter Perren, who had been gravely injured in a Warden training climb on Mt. Logan months earlier, and were assigned to gather and catalogue all the information we could find, as it related to those. mailings and Warden operations. Together we meticulously put together a four-inch binder which chronicled the entire incident, including bear activity around the town that led up to the first mauling. It helped up put together and understand that whole series of incidents. That binder stayed under lock and key for about maybe 15 years because of court cases.

The third and final mauling (all by the same bear) really stands out in my mind. By that time, we had spent weeks thrashing through the dense bush, looking for clues, dragging beaver and elk carcasses create scent lines, setting traps and snares for bears, and trying to figure out what was going on. Two bears had been shot, and one of them positively identified as the attacking bear by one of the victims. It was after the second mauling, and I was out with Steven Herrero and some of his students doing berry transects to figure out if a food berry shortage was related to the attacks. The radio crackled: somebody else had just come running out of the woods by the hockey arena and they’d been attacked by a bear. I was nearby so I went roaring into the parking lot, arriving at the same time Rick Kunelius pulled up in his truck. We went to the ambulance, and talked to the guy. He was okay but bleeding and being taken care of. He told us where he came out of the woods so we went to that spot and we could see blood, his blood. So we followed the blood trail into the bush. Probably about 30 meters into the bush, we came to a tiny stream with maybe just two or three inches of really clear water, over a sandy bottom, about a meter wide. We could see this guy’s boot prints, where he crossed the creek. So, as we across the creek, we looked downstream. There was a perfect footprint of a bear – it was an inch longer than my hiking boot, absolutely massive! And I tell you that the hair on my arms is standing straight up right now, just remembering that sight. That was the first moment, of a week-long investigation, that we realized that there was a grizzly bear involved in those attacks. There was no other inkling. And that was a massive bear. On the edge of the stream was the place where the guy had tried to hide under a young spruce tree. The bear had roared around that tree, and scratched him up a little bit. It must have been chaotic, because loose feather moss torn from the ground was hanging from branches 10 feet from above the ground. The entire investigation re-started, but we knew then that we were dealing with a very large and very wily grizzly. Earlier in this interview, I described the death of that bear at exactly, 0747 hours in the morning. I was part of a cadre of Wardens that ringed the area on many nights; standing on the railway tracks, lying on top of railway cars, posted along the highway and surrounding that whole area armed with shotguns. There were traps set and snares set too but that bear had been going in coming at will, in between us without any sound or sighting. I don’t know who pulled those triggers, but I was not far away, along the Mt. Norquay Road when the shots came.