(I asked, “Were you involved with the International Peace Park with Glacier?”)

Yes, I was heavily involved with that. We had joint management meetings between the management teams of both Peace Parks, but the Wardens and the Rangers also work closely together on rescues. Waterton went down and did a lot of the technical helicopter-sling rescues in Glacier. We supported them, they supported us….that included all of our programs (law enforcement, resource management, planning, research, etc). In 1992, I started an annual Warden/Ranger meeting with the Chief Ranger (Steve Frye) down there. We would meet for two days in each country (alternating each year). It included a social event in the evening plus we exchanged a lot of information and learned a lot from what others were doing. To a large degree, the Crown Managers Partnership came out of that as we talked about expanding the Peace Park concept to include a lot of other land and resource management agencies in the larger regional ecosystem. Other federal, provincial and state agencies might have a different mandate but we often have common goals and objectives. The Peace Park was established in 1932 through an Act of Congress and Parliament, arising from the lobbying efforts of Rotarians. I tried a number of times to do some unique things like creating one Management Plan for the two parks, but that was tough, because it was two countries. But we did agree to some broad principles that we should both consider in our Management Plans. Some of the folks I worked with are still good friends and we keep in touch through canoeing and other activities. You develop lasting friendships through these relationships.

MH: Can you tell me about any rescue/wildlife stories that stick out in your memory? 2420:

BD: There are a lot of stories but wildlife sightings themselves were incredible. On the north slope of the Yukon, I was with an Inuvialuit patrolman (Andy Tardif) as we did the first canoe patrol down the Babbage River. Near the end of the trip, we were paddling through the Babbage River Delta into the Beaufort Sea. It was late in the evening and, all of a sudden, these little heads started popping up around the canoe. I wasn’t sure what they were initially as it was getting dark. Then we realized they were seals, as we were close to the ocean.

Or another time, we were working through the night (you get 24-hour daylight in the summer up there) and we were flying out of the British Mountains to the Coastal Plains and the Beaufort Sea. All of a sudden we hit a cloud bank and lost visual on the ground from the helicopter. We saw a small hole in the clouds and the pilot took us through the hole and pulled up. As we came through the clouds, we looked down and it seemed like the whole ground was moving. We realized that there were about 5000-10000 caribou crossing the Firth River.

Some other sightings were so rare, like 6 cougars one winter evening in the Waterton townsite. They were probably two females with two cubs of the previous year and they were all big cats. It’s rare to see a cougar but even rarer to see 6 at the same time. Or the black bears in Riding Mountain, seeing a sow with 5 cubs two years in a row (in the Moon Lake area) which means there were two different sows having that many cubs…very productive habitat. So those are some of the observations.

2630: I looked after the Bear Management Program in Riding Mountain and this is a story where I learned very quickly about the media. In Riding Mountain, the bears were under a lot of pressure from people – hundreds of black bears were shot in the early 1980s around the park, every year. The bears would get into conflicts with agriculture, getting into oats, granaries, etc. There was pressure on the bears inside the park too and we were regularly relocating black bears that had conflicts with people. In my last year there (1983), we made a decision to destroy bears rather than relocate them since, invariably, they came back very quickly and were usually killed after more conflicts. We didn’t have any bear proof facilities. We had a dump that was wide open to bears. The real problem (garbage) wasn’t being fixed. So we forced the issue. We started to destroy habituated bears that year instead of relocation. Of course, it’s never easy as a Warden, but we shot 22 black bears that summer. I was asked to do an interview with CBC in Winnipeg about that because they wanted to compare and contrast Riding Mountain with Northwest Ontario where they were relocating black bears. I went into Winnipeg to the CBC building. They put me in the front of a car and we drove to a green area for the interview, with the cameraman in the back. We got there and they did the interview for television. Anyway, they were asking questions in the car before and after the TV interview. After the interview, they put the camera down, but I could still see the tape was rolling. So the reporter said, “So what does it feel like to blow away a black bear”, a very loaded question. So I explained that nobody likes to do this especially since we are in the business to protect bears. But anyway, as it turned out, they only had a 30 second interview on TV but a longer interview on the radio. They had been recording audio that the whole time, in the car during the casual conversation. I guess the lessons that I learned were to be guarded with the media and that sometimes controversy is good thing. Ultimately a couple of years later, Parks Canada fenced off the dump, put bear proof containers in the townsite and a lot of the root cause of the problem was fixed. So that was a good story.

Another story I thought of was when I worked in Wood Buffalo. I worked with Dr. Ernie Kuyt (Canadian Wildlife Service) who was responsible for the whooping crane recovery project. Ernie had so many years there, taking one egg from each nest for a captive breeding program in the United States, helping to bring the whooping cranes back. And as a Park, we felt that we had a role there but Ernie had been doing that for years and CWS had the lead responsibility. At the same time, we were concerned with the potential impacts of dewatering activities from a mine north of the Park (Pine Point mine). We saw an opportunity to establish a shallow ground water monitoring program in the whooping crane nesting area. The nesting area is a very wet area and that was critical to chick survival. If it got too dry, the nests could be accessed by more ground predators or be threatened by wildfire. So we worked on habitat monitoring and that was a way for us to contribute to the whooping crane recovery program. I was also part of helping to write the first whooping crane recovery plan. I think our approach helped advance the profile of both Parks Canada and the Warden Service.

MH: How did the Warden Service change over the years? 3040:

BD: Well a lot, in terms of how we protect the parks but not the primary role of protection. The tools that we use, and the different pressures facing Parks, has changed significantly. But the primary role of protection remains the same. Although law enforcement has been separated from Resource Conservation – to me all of this is still the Warden Service. The Warden Service has always adapted and changed over the years while staying true to its role in protecting the parks.

I came into Parks Canada in the 1970s when many Warden Stations were closing and staff were moving to centralized locations. When I was offered my permanent warden position, I was leaning towards a job in Wood Buffalo (Fort Chipewyan) as I always wanted to go north. My Chief Park Warden in Prince Albert, Dean Allan, really encouraged me to take my permanent position in Riding Mountain at the Sugarloaf Warden Station (south of Grandview, MB). He said, “you can go north later”. It was good advice because I was able to work out of a District Warden Station at a time when they were starting to disappear. It wasn’t just me. My wife, Debbie, and the family, were a big part of the Warden Service. Families played a big role, especially at Warden Stations. In Riding Mountain, the Warden Stations provided important links to people and communities around the Park. Families were a big part of those connections. I remember the Rolling River fire in 1980. All the Wardens were seconded to the fire for about 3 weeks but families were still at the stations. Debbie was looking after the horses in my absence and providing a public contact for the park. I was lucky to have been part of that, working at a District Warden Station, as most of them have been closed now.

Riding Mountain National Park_1980 Debbie Dolan, Red and Shep at Sugarloaf Warden Station

Another change that I’ve seen is big improvements in the professionalism and training standards in all of the programs, Law Enforcement, Public Safety, Resource Management and Ecosystem Management. Parks became a leader in many areas, whether it was in Bear Management, Fire Management or Public Safety, rescues. There was a continued progression of high standards.

Another change, was the significant expansion of the Parks system in the 1970s, 1980s and beyond. Expansion of the Parks system really changed the focus of Parks Canada and the Warden Service, especially in terms of our relationships with indigenous peoples and their traditional use and rights in national parks. It was often a big change for a Warden coming from the south to Wood Buffalo, seeing hunting and trapping going on. I used to go out with one of the local trappers (Gabe Sepp) every year on his trap line for a few days. Those experiences helped to broaden the scope of park wardens as they moved around and worked in different national parks. And of course I mentioned ecosystem based management approaches and science. That was really another significant evolution over my career. Again I have to say, the thing that I always valued about the Warden Service was how it adapted to those changes. You went and got the best and the brightest, and you saw that openness in many of the old time Wardens. Even though some of the older wardens might not have the same background or education as the new recruits, they saw the value in the future; they were thinking down the road.

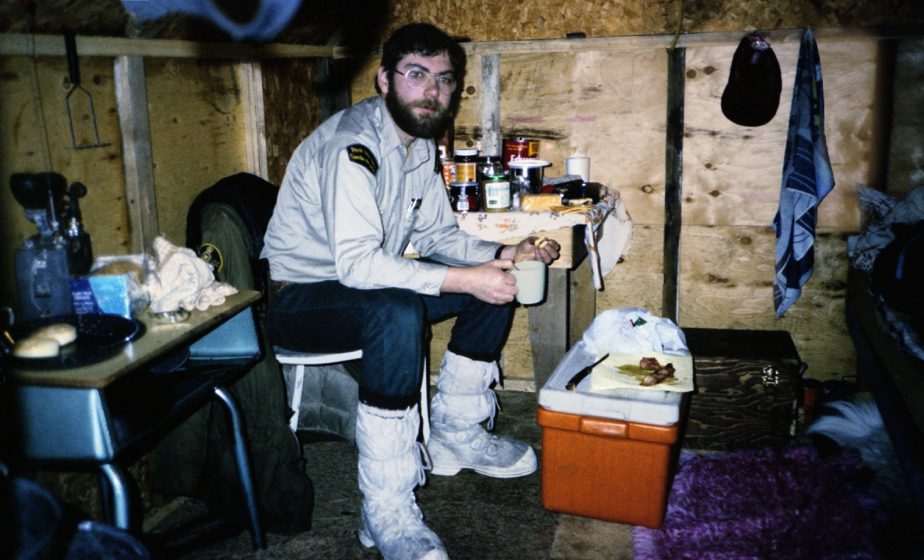

Wood Buffao_1986_Bill Dolan at Gabe Sepp (trapper) line cabin

MH: What about the Warden Service was important to you? 3550:

BD: Ultimately the protection of the park was most important; to me, that was the bottom line. That said, you can only achieve protection through your relationship with people. The Warden Service has always had a focus on the interface between people and the natural world. For Law Enforcement, the focus is on peoples’ impact on the resources. For Resource Management, the focus is on the impacts of people on the resource and vice versa, such as fire or bear management. With Public Safety, you’re looking at the impact of nature on people through search and rescue. Ecosystem based management, including science, takes you outside of your boundary to more effectively manage all of those programs. Those are really fundamental programs for the protection of parks.

MH: Are there any legendary characters or stories associated with the Warden Service that you can share? 3712:

BD: Probably two things and the first is a general comment. I think there are a lot of legendary characters because they often were quietly doing their job and doing it better than most Wardens, but they didn’t create maybe the big stories that got captured around the campfire. Gordon Bergeson, was one of the best Game Wardens in the system in Riding Mountain. There was also Gordie Mason (quite the character) who took the fire program in Wood Buffalo to a whole new level. Derek Tilson was a leader in Waterton and challenged management and peers to do a better job….and often in a light hearted and humorous manner. There were lots of people in my career who you just look at and say “wow”. They often are not well known or, at least, don’t have the profile of some legendary characters.

3820: The one incident or story that I can share which was, in part, my story. It was a poaching incident in Riding Mountain. When I came to Riding Mountain in 1979, there was a lot of poaching and district wardens had often worked independently in different backcountry districts. We started getting very aggressive with poaching enforcement. Art Cochrane was one of the persons who really promoted this, another great person in the Warden Service. Wardens started working together more and supporting each other. We scoped out where there were poaching problems and we established warden camps in those areas, listening for activity and rifle shots. We ended up having a lot of success. After hearing shots, wardens from other Districts would converge along the park boundary at different exit trails or routes to try and catch the poacher(s) as they were coming out of the Park. In addition to those strategies, I developed a trail inventory and law enforcement plan to support our response. That’s some background leading up to one of the many poaching incidents that I was involved in. In September 1983, one of our camps heard shots northwest of the McKinnon Creek Warden Station (NE part of the Park). At the same time, we knew there was a person in the area named Danny Dauphinais who was a well-known poacher and also had a violent background. He had been charged with attempted murder and was prohibited from owning a firearm for a year. Given that context, we tried to contact the RCMP to assist us but they weren’t available. We pulled together 6-8 wardens and we trailered our horses over to the park boundary near the trails that we thought the poacher(s) might come out on. We put four wardens on the most likely exit route for the poacher(s). Myself and another Warden, Bruce Sundbo, lined up on the another trail (Anderson Trail) in the same area to wait for the poacher(s) as they left the Park. After waiting for a while, we heard horses coming and got on our horses. Our approach was based on a technique that Gordon Bergeson had used. He would rush the poachers as they came down the trail, usually below a meadow or open area. As he rushed their horses, the poachers would often turn around to ride back up the trail. Gordon would catch up to them in the meadow so he could get alongside their horses. That was the concept. Well in this case, they were walking and leading their horses because they were carrying 6 hind quarters (4 moose and 2 elk) of meat on their horses. As we rode up to them, they had nowhere to go. Dauphinais pulled out his rifle, pointed it at us, cocked the hammer back and there we were. We had made an assumption that didn’t work out. Long story short, he checked to see if we had handguns and took our horses. His wife was with him. At the time, Dauphinais didn’t know we had recognized him. He also took our radio but we had another radio in the bush so, after he left, we contacted the other wardens and said we’d run into him (Dauphinais), “He has taken our horses, back off and let him go.” Before we had hardly finished, he rode up the trail again because he heard our transmission on the other radio. He kicked me in the back of the head and took the other radio. You could see that he was getting agitated and then he headed back down the trail. Shortly after that, I said, “You know Bruce, we shouldn’t be on the trail! We’re pretty obvious.” Dauphinais now realized that we knew who he was and he had a firearm when he shouldn’t. So we moved off the trail into some thick bush and hunkered down for a bit. Within a few minutes of getting off the trail, he rode back up the trail passed us. We weren’t sure what he was doing or if he was looking for us so we decided to stay put for a while. Eventually, we could hear people calling for us but we didn’t know where Dauphinais was so we kept quiet. Finally we decided to walk out after midnight and there was an RCMP member in his car waiting near the boundary. The next day, we rode back into the area and saw where he had cut his load of meat loose before he found another route out of the Park. Bottom line he was eventually caught in Winnipeg, charged with armed robbery and sentenced to four years. I was disappointed that they dropped the poaching charges but I guess they were minor compared to the other charges. That was one story I was involved in but there were lots of poaching incidents you could talk about in Riding Mountain. Lot’s going on.

MH: Is there anyone from the Service that stands out in your mind? 4310:

BD: That’s what I was thinking when I mentioned some of those names like Art Cochrane. These are names that brought real strengths to the Warden Service. People like Art, Derek Tilson, Jacques Saquet, Gordon Bergeson, Gordie Mason; these are just a few wardens who in my mind are legends because they did some incredible work and maybe weren’t noticed as much as others. But, there are many more….

MH:Is there anything about the Warden Service, as you knew it, that you would like future generations to know?4430:

BD: Protection is really our fundamental role in the Warden Service but you have to do it through people. You have to work with people both inside and, more and more, outside of the Parks to be successful. I think the Warden Service has always done that but as pressures changed, I think there was a more outward focus than there used to be.

Remember to be loyal to the mandate and the mission, the policy and legislation. For example, I was a little disappointed with the senior management culture in the latter part of my career. I had a new superintendent who, shortly after arriving, told the the park management committee, “My most important value is loyalty”. I’m pretty sure he was echoing what was coming down from up higher in the organization because he was a good manager. But I thought, “You don’t ask for loyalty, you earn loyalty.” And so always, keep that focus on the Parks Canada mandate but be sure to listen to what others are saying. Create a big tent and invite lots of people into it, especially people who might disagree with you. Be strategic and really focus on actions and outcomes. As Art Cochrane once said to me, “Just do it!” It’s very important to be strategic, to plan and involve others, but you also have to get results.

And I guess the last thing, that I think has gone by the wayside a little bit, relates to staffing and development. In 1990s, the Warden Service was building on and developing a human resource management approach. It started with the initial recruitment and a focus on getting the best people into the organization. The recruitment process was focused on abilities and personal suitability; knowledge was only 10%. We really wanted good people who had a lot of potential. We hired recruits who started out in a generalist role but provided opportunities for career progression to specialist positions in all the programs. Initially you got exposed to a number of different areas and that approach built tremendous bench strength down the road. It created a very efficient organization. It also allowed you to appreciate what someone else was doing if you moved into a specialization. You understood what was happening in another program and why it was happening. It started with the Warden Recruit Training Program. It was just an excellent program that grounded people in the Warden Service and Parks Canada. You recognized right away that you were a part of a much bigger organization as you met new recruits from across Canada. I think that integration and cohesion, both vertically and horizontally, was a real strength. Unfortunately, it was may be seen by some senior managers and others with some jealousy, in a negative light or maybe as a threat. That said, if we had adopted that human resource concept/model to Parks Canada as a whole, and included much of the organization in that model, I think it could have been a much more progressive approach. I think we may have lost that opportunity, but I can’t say for sure because I’m not part of it anymore. But like anything else, change is like a pendulum it swings back and forth. Hopefully, it can get close to the centre as opposed to either extreme. That was the only other thing I would say.

MH: What made the Warden Service such a unique organization? 4945:

BD: I think I have touched on that with the horizontal and vertical integration of all the programs and working with people, as well as the resource. I still remember in 1995 I helped organize the International Airshed Workshop in Waterton with the United States Parks Service and folks from Ottawa and Calgary. We were sitting inside the conference room on the first day and it was pouring rain outside. By early afternoon I realized I couldn’t sit there anymore because I had to go help with the flood response. So that example just speaks to the depth that the Warden Service created in its staff. Even if a warden was working in resource management or law enforcement, if you needed someone to step into help with the Public Safety Program, they were there. In the smaller parks, they were wearing a different hat every day. You couldn’t find a more efficient and effective approach. This created tremendous depth and capability in staff. At the same time, most staff remained open to changes. Finally, and most important, an organization always needs to cherish the value of “speaking truth to power” and then reconciling the path forward in a respectful way. Often the issue is really just about effective communication. That value is a sign of a healthy organization.

MH: Do you have any lasting memories as a Warden? 5130:

BD: I have lots of good memories. In the early years, I’d mentioned these poaching enforcement camps in Riding Mountain that we had set up to listen for gunshots and poaching activity. In 1981, we were living at the Sugarloaf Warden Station and I had organized a camp in the Renicker area which was about 16 km southeast of the Station. I wasn’t in the camp but was outfitting it since we changed warden staff in the camp periodically through most of September. I was staying close to Sugarloaf as we waited for the birth of our first child (Carrie). As it turned out, she was three weeks late and was finally born just before we took out the camp. Debbie was still in the hospital with Carrie and I headed off to the Renicker for the night with my pack horse, camp supplies and, of course, a couple of bottles of rum to celebrate our new arrival. It was turning dark as I started the ride but the horses knew the route even though it wasn’t a formal trail. There were two people in camp, a warden from Vermilion River Warden Station (Clint Toews) and a RCMP officer from Dauphin (Dave Shillingford). It wasn’t long into the ride and I heard gunshots. It’s dark, so I radioed Clint and asked what was going on; if somebody was hunting in there now. Clint said, “No, I guess there’s a skunk in camp and he’s getting into our meat so Dave pulled out his side arm and is shooting at the skunk.” I was relieved and finally got in there about an hour later in anticipation of sharing a few drinks with some friends. I soon discovered that the cap on the larger bottle of rum had come off (seal had been previously broken) and soaked through my sleeping bag. All we had was a small bottle of rum to celebrate Carrie’s birth and I had to sleep in a wet, rum soaked sleeping bag. It certainly smelled like we had a good time!

That was one story and another one comes from Ivvavik National Park. The military wanted to put a short range radar site in the National Park at Stokes Point along the Beaufort Sea coastline. Parks Canada really didn’t have the muscle at the federal table with the military in terms of some conditions. If they wanted to do something, they were going to do it, and you knew that. So I went over and talked with the Inuvialuit and they said, “Tell us what you want to achieve out of this”. We discussed our shared goals and, not surprisingly, we were on the same page. The military showed up at the meeting a little later. I didn’t have to say too much as the Inuvialuit had all the leverage through their land claim settlement. To their credit, they basically ensured that what we wanted to achieve as a National Park was put into that agreement. It’s an example of how you can get your protection done through others who have shared goals.

And the last example would be from Wood Buffalo. I was on a winter patrol for a week into the Needle Lake cabin with another warden, Jacques Saquet. It was -35C weather the whole time. We were trying to find an old trail that used to go all the way down the west side of the Park past the Caribou Mountains to the Garden River settlement on the Peace River. The Wood Buffalo Fire Management Officer, Gordie Mason, had told us about it and provided some suggestions to locate the route. As I recall, we didn’t have radio coverage in that area so we had just told Gordie when we’d be back to the trucks. On the final day we were about an hour late coming out to the trucks and we saw a small plane come over us, tip its wings and fly away. When we got back to Fort Smith, we found out that Gordie was concerned about us given the cold weather and he was coming out to look for us. That speaks volume to how wardens looked after each other over the years. So those are some fond memories of the people and the places…….and there are so many more.

Bill you had a great career in the Service, i was glad to have worked with you.