We had one exercise where we carried a stretcher from Florentia Bay, around the headlands and shoreline, all the way to Wickininish Centre. We actually set up a Tyrolean traverse across a surge channel using cable rescue gear. Gord Irwin was on that, and someone else from the mountains. So that was pretty cool but just a horrendous gut slog doing a stretcher carry around all those rocky headlands, up and over, and traverse across a surge channel with the cable gear. So the surf guards trained in all that stuff and we actually did some heli sling training with the Billy Pugh which was a ring with a fish net enclosure attached to two big hula hoop rings, so when it was hanging under the machine, the top hula hoop ring and then the fishnet around, 360 all around, and then tied off on the bottom hula hoop ring and then there was slits in the side of the fish netting that you could get through.

The idea was the rings would collapse, and you’d drop this thing in the surf, and then slowly raise it up so just the bottom ring was weighted, and so it would sit right at the surface of the water, and then you could swim with your victim into the bottom of this fish net enclosure. Then you could clip in and then the helicopter would raise you and the patient and sling them over to the beach or the airport tarmac that’s right behind the beach there. It was a way to adapt the heli sling rescue to that water environment. Anyways, we’d had at that point in time they’d instituted the advanced first aid training as well, so we were all young and keen and had taken all of this training. I think I was one of …I was the only Warden at the Warden Office when the call came in, and it was a call from a payphone down at Wickininish Beach and it’s this woman that was in obvious distress.

She said, “My father has disappeared in the surf.” So I got the details and I put the call out to the surf guards who were all up at Long Beach at their surf guard tower, and to Mac Elder who was the Chief, and on the radio. Dan Vedova was on (duty) and then I got in my wet suit and got the rescue board and headed down, and I met this young woman and her two friends at one of the beach accesses there at Wick. We ran down onto the beach. The conditions at the time … there was sort of a moderate sized surf, but the big complicating factor as it turned out, was there was thick, thick fog. You just couldn’t see. What she said happened was her and her two friends who were along with her and her dad on this camping trip had gone into the ocean and they were all in swim suits. Her dad was a very committed ocean swimmer and he tried to swim a mile a day every day. They lived near the ocean in Vancouver. So he wanted to go for a swim and they all went into the water, but what they weren’t used to was the rip currents. So, at Wickininish Beach at that time there’s a real strong longshore current parallel to the shoreline and as they walked out they were sort of knee deep and then thigh deep and then all of sudden all of them dropped into this trough carved out by the longshore current of deeper water. It’s like a river channel, like stepping into a river. They couldn’t touch bottom and they’re going sideways. So the girls right away just made a scramble and swam very quickly until they could touch bottom again. And he said, “I’m okay, I’m going to do my swim, it’s fine” and he swam off into the fog. And his daughter yelled at him I guess, and he said, “No it’s fine and then he disappeared into the fog and he didn’t show up”. She was already anxious with him, not being able to see him and she didn’t wait too long before she called, and I responded as quickly as I could, so it wasn’t too long after the call that I was there. She showed me where he went into the water, so I relayed all the information to everyone that was on their way and then I headed off on my surf board into the surf, into the fog, yelling his name, and had his daughter and her friends go and wait in the parking lot and direct everyone down and explain everything.

Pretty soon I could hear Dan arrive with his board, and the surf guards arrived with their boards and pretty soon I can hear others yelling this fellow’s name. We can’t see in the fog but we can hear each other, but not hearing any response. After awhile I decide to paddle back in and ask Mac …. apparently Mac was running the response with a radio from the beach. So I was going to go find Mac and see what other resources we could get. Nowadays one of the first calls would be to Coast Guard, but this was in 1981 so we just didn’t have that kind of working relationship with the Coast Guard at that point. Anyways I hit the beach and I can see Mac off in the distance, and then just as I see that, I look and I can see this fellow and he’s come in on the surf. The surf is rolling him on the beach sort of thing. So I go and I pull him out of the surf and I check and he’s non responsive and Mac can see this. So I start CPR and then the word gets out to everyone else. Dan Vedova showed up just a few minutes after that. He had the same idea to come ashore and see about more resources. So we start doing two person CPR, and then pretty soon the surf guards were with us and we all took turns doing two person CPR. Meanwhile the call has gone out to the ambulance and so his colour started to come back and we were able to get breaths in and so we were hoping against hope, because it was really cold water and he wasn’t wearing a wet suit but maybe there’s a chance …. So we kept up the CPR and it took a fair while for the ambulance to get there and then we carried on CPR up the beach on a stretcher, and then in the back of the ambulance and they said, “You guys seem to be doing really well here, just keep it going”. So we arrived at emerg at the hospital and they got him hooked up to heart monitor and everything else and the doctor said the same thing. He said, “You are getting good perfusion and I could see your rhythm is really good, just keep going” and every once in awhile we’d get a little spurt of spontaneous electrical activity, but finally the doctor called it. But it had been … We’d been doing CPR for close to two hours I think.

Of course, we were all pretty devastated, and what we didn’t know at that time but we learned that evening was this fellow, he had a very large family, I think it was 12 kids, and we were sort of …. I was questioning myself and all of us in our debrief, you know, should we have started CPR. But what ended up … the wife and some of the other kids that arrived ended up staying with me that night at the Eight Plex so I learned a lot more about their family the next morning. They really appreciated how hard we worked and that we did start CPR and kept it up. It was a small consolation to them, that we had done everything we possibly could and they were so appreciative. So, that was a real tough one. I also learned, even in those situations where the outcome is the worst possible outcome, that our efforts and how we perform, how important that is to those who are still here. That was early in my career and really made a big impression. You always want to be in that rescue where everything works out but that’s the other side of public safety work. Are you still there?

SH: Ya, sorry, I’m just thinking about that. (Tape 17:24) I just remember some of the stories of drownings that happened there and how sad they were.

Bob: If it’s okay I have one from the mountains that did turn out well….

SH: Go for it.

Bob: When I was in Rogers Pass I would go up and volunteer on the avalanche control at Marmot. Then the first winter when I was up working in Jasper, I actually got extended for the winter on avalanche control at Marmot. It was so great, that was such a great winter. I was coming down the mountain, down the Marmot Road after a day of work and was part way down the road when a call came in where there’s a fellow and he is in distress at Shangri La cabin. One of his close friends is with him who’s a nurse, who knows his medical condition and she thinks he may be having a slowly unfolding heart attack. Everyone mobilizes of course and Gerry (Israelson) is the lead public safety guy at that time. So, we all meet at the rescue room and there’s quite a good response, there’s quite a group of us, and then we decide to go stage out of Maligne Station and we grab some double tracks and all our touring gear and stuff and oxygen equipment and trauma kit and all the rest and then we head up to Maligne.

Meanwhile a storm system has moved in and it’s starting to snow, and by the time we get up to Maligne, it’s dark and it’s snowing heavily. The thought is that we’ll try and get a machine …. go in with the double tracks over Little Shovel Pass from Maligne. There’s part of the cross country ski trail system up to Evelyn Creek that is already broken, and maintained so that will get us to Evelyn Creek, and if we can get up over the pass ……So, we head out in our teams and the snow just starts falling heavier and heavier. We get part way up to Little Shovel Pass and there’s just not enough base in the snowpack. We’re getting stuck over and over again and it’s just not going to work. So we backtrack. So then Gerry makes a new plan. The new plan is that Pat and Greg Horne and myself will ski in going the regular Shangri La route up from Big Bend on the Maligne River and ski into the hut. So we do that and then they’re going to work on additional plans as well. But we head out and we’ve got the oxygen and trauma kit.

So we get across on the ice on the river and then we find the trail in the forest which isn’t too hard to find. It’s still distinct and it’s in the forest. So that goes well until we hit the open meadows when we’re sort of in the upper half of the valley going up to Shangri La. Now we’re in the open and it’s blowing snow and we can’t see very far. But what we end up doing… you know sometimes when a meadow like that, when the wind is working on it, the old ski track can end up being … you know the snow erodes around it, so you can almost see a little bit of the elevated hardened old ski track. So we could see that from time to time. And then it got to where the new snow had covered it up, we could feel it under our skis. So we did that, we sort of felt our way on the old ski tracks in this blizzard, and we got there finally. He was still in distress but as soon as we got the oxygen on him he started to improve right away. They were very, very happy to see us. Then we went out. So the plan was when we got there, was to work on making a helipad so that when daylight came they could fly in and get him out. So then we went out and spent the next couple of hours stamping out a helipad in the snow and by then the storm started to break, so things were looking up. We went back into the hut to try and get some sleep, but I think we were too amped up on adrenalin. So there wasn’t really any sleep. We were listening for the helicopter, and sure enough, here comes Garry (Forman). We get him out there and off they go. So that was one of the good ones. We eventually got out and I think we were going straight for 26 hours from the day before to when we started work to when things ramped up….

SH: A nice overtime cheque.

Bob: We felt pretty good but it was sort of neat with Pat and Greg and figuring out just how we were going to do this in this blizzard. We can’t see and whatever but we just worked it out …. carried it off.

SH: Do you want to go on to how the Warden Service changed over the years Bob? Or do you want to tell more stories. It’s your interview so you decide.

Bob: I’ll tell you the wildlife one and I’ll leave it up to you. (End Section 3 – Tape 26:17)

I was working on … for three winters there I had the job of doing the winter data collection and field program for the mountain caribou project in Jasper. At the start of each winter Kent Brown would try to capture and radio collar a number of caribou early in the winter. So that was going on and we were working up the Maligne Valley.

There was Todd (McCready) with the machine (helicopter) and then Kent and myself and the idea was we’d stage out of the Beaver parking lot. The caribou would often be out on the delta there at the end of Maligne Lake grazing, so we knew that they were not too far away. We got up there and sure enough we could see the herd, a small group there.

Kent made up some darts and when we were flying up to Beaver, he informed me of the emergency medical procedure that we’d follow, and because we were using carfentanil which of course everyone knows now, but at that time I’d never heard of it. It is a super lethal drug for a human. So he gave me the Narcan syringe and said if I accidently prick myself you’ve got 20 seconds to shoot this into my mouth or I’m dead. So that was on the flight up. So he made up his darts and then him and Todd lift off and I’m waiting back in the parking lot. So they take the door off, and Kent’s got a little harness and he leans out and stands up on the skid. Todd would get low over the caribou, trying to get them running in deep snow so that he could get them not going too fast and get over them and dart them. Very quickly Kent has an animal darted so he’s on the ground with the caribou and I think Todd just sort of hovered. I think Kent just did a hover exit with his gear. But as he’s about to start working on the animal, the animal starts to get up. What he figured happened was that it hit a bone maybe and so the animal got a little bit of drug but not very much. It’s pretty hard to … every collared animal is so key to this research project, so Kent decides that he’s going to try to tackle the caribou and pin it and he does. He manages to knock it over but then he starts to slide off and so what I hear on the radio from Todd was “I’m on my way, don’t ask any questions, just hop in as soon as I get there.”

So I don’t know what the hell is going on but I do that. He doesn’t set down he just hovers, I hop in and we get back across the lake and here’s the caribou, and Kent has slid down so now he has just got the lower end of one leg and the caribou is dragging him through the deep snow. So Todd says “Okay, I’m just going to hover over the animal, and you jump off and grab him.” So I get ready on the skid and Todd gets me right over so I hop off and bulldog, like grab the antlers, and bulldog the caribou down, and hold him down.

Kent is a little bit battered. He was totally exhausted, but sort of shakes his head, and gets himself collected and gets another dart out and injects the animal and then we processed the caribou and get him collared. And then give him the reversal and he’s up and away, and amazingly that caribou survived. He did okay and we ended up tracking him for some time. It was a bit of a rodeo, it was pretty fun. But not according to the policy and procedures though. (Tape 06:23)

SH: Glen told me a story of grabbing a cougar by the tail, kind of a similar rodeo story, trying to dart a cougar.

Bob: Is anyone interviewing Marv?

SH: Millar? Yes I think he’s been done.

Bob: Do you know if he told the story about doing artificial respiration on the cougar?

SH: I don’t know, I’ll flag that one for Marie.

Bob: It was bad drugs back then. It was anectine, and the animal is fully aware but it paralyzes the muscles.

It was a cougar with two kittens, or young cubs up on Pyramid bench and it had been eating cats I think. It had been living under a trailer in a mobile home park there.

SH: I remember that one Bob.

Bob: So they treed it and darted it and then it went into respiratory distress. Al Stendie and I got there in time to witness Marv giving artificial respiration, trying to keep the mom alive but he had to give up finally. They kept the cubs at the Warden Office in the dog kennel there, for I forget how long, and then they flew them up into the Snaring. I don’t know whatever happened with them.

SH: Do you want to go on to how did the Warden Service change over the years?

Bob: I don’t want to be bitter and twisted.

SH: You never were.

Bob: Rick Ralf and I took an oath back in the 70s. Rick had been in Jasper, started in ‘74 in Jasper, and he’d been in Banff I think starting in ‘73. But early on in our career there in Jasper we saw … there was a whole cohort of Wardens that were finishing their careers and so we made a note to ourselves that we would not become bitter and twisted. So we worked hard at keeping that oath over the years, but as time went on we came to understand those guys that were retiring at that time. How, over the course of your career you just see so much change, like I’ve talked to you before sometimes, it’s just mystifying the direction that’s charted out for the outfit. I just feel super fortunate to have worked in the era that I worked, and where we were just …. that era where we all trained together all the time, on every aspect of things; fighting wildfires, law enforcement, first aid, wildlife handling, search and rescue, climbing. As an organization, not only just our parks, but all the parks together. There was regional schools and national schools and then all the regular training within our parks. We just formed such strong bonds amongst ourselves and also the families. The families were part of the outfit too. The partners and the kids, it was just like one giant family. We had get togethers often, the partners were part of responses, and many times they were the person that answered the door at the station if someone came in reporting some emergency while the other person is out somewhere else in the field. They’re taking all the details and looking after the person in distress that’s reporting it or whatever.

The outfit was a real outfit and it was so tight knit. You really developed an appreciation that together the outfit could deal with anything. It just didn’t matter what it was, we could deal with it collectively. It was like at Rogers Pass, just like one big family, all of us. You in Dispatch and, (Snow Research and Avalanche Warning Section) and NRC (National Research Council) and the truck drivers. All those sort of shit storms in Rogers Pass, we could do it. We came to believe that very strongly and we did over and over again. So, it was pretty amazing to be part of that.

Like I was saying, when they didn’t fill the alpine specialist positions, when the organization started to sort of lose ground in terms of all the various things that we did. Partially, I can understand, it’s like with the sidearms issue. I was really torn back and forth on that issue. I was in Pacific Rim at that time and in a small park like Pacific Rim, where we were responding ….we’d be dealing with a bear in the morning, and a party that night and in between we’d have someone break a leg on a trail or the boardwalk or something. As the years went on, and our visitation kept climbing from a few hundred thousand, it started creeping up towards a million visitors in a tiny little park in the busy season, and then you’re getting a call and having to go to Green Point walking into what you’re not exactly sure, and you’ve got your duty belt on and your vest, and you’ve got to switch your mind over to being a totally focused professional enforcement person. You may be doing all those things in the course of a single day and just go “Well this is getting tough”.

When they …. you know I thought the organization, that we’d be okay with the decision on the sidearms issue and creating totally specialized enforcement branch, with the thought that those Wardens that go over into that role, when they’re replaced, when those positions are refilled, we’ll have a much better, incredible organization. But when they decided those positions would not be backfilled then we just went “Wow”. Now we’ve lost these people that individually had so many skills and so much knowledge and experience as generalist Wardens, and now we are being told that they can’t help out in a rescue or with a bear or that sort of thing and there’s no one to fill the hole they left. That’s when it just was “Wow, we’re behind the eight ball now”. And then we were all, a lot of us, went into specialties as well. So now we were really …. How to deliver public safety? How to keep up our training in that role in a small park setting? How do we keep up our skills to go and land through the surf on the West Coast trail and get out through the surf and package a patient and look after him, and get him to the ambulance, and also be a specialist at something else? And then the increasing administrative role. It seemed like things were constantly coming down the pipe and landing on our computers that needed detailed responses and involved more time and energy to deal with and added again to that feeling about being stretched thinner and thinner. (Tape 18:40 – End Section 5)

SH: What about the Warden Service was important to you?

Bob: Well I think starting in the organization in the mid ‘70s there, when there was this whole cohort of what to us were legends, that were retiring and hearing their stories and being trained by them and seeing the reality of their careers and everything that they contributed over their careers to that grand vision of …..these are jewels of Canada and the world really, that we’ve been entrusted with a responsibility to, not just say the words but really, every day do our part to protect those places and the people in them and the wildlife and everything, as Wardens but also as part of the larger National Park family; the Interpreters, the Visitor Services, the Trades people. You might get a similar answer from someone driving snowplow at Rogers Pass, to a Campground Attendant, or someone who worked at the Gate, or a Trail Crew worker. We all felt that responsibility as being part of the National Parks. As a Warden, I really felt right away that there’s a tradition here. It’s a continuous tradition and it’s a real privilege to be part of that tradition and to try and live up to the examples that the others have set. So that’s part of what made it so rewarding.

Being part of a common enterprise with all of those people that work in National Parks, and with the Wardens, having lots of different responsibilities and sometimes very heavy responsibilities, but having confidence that we can do our part and having fun while we do it. All of those potlucks in Rogers Pass, and everywhere …. the sauna parties, you name it, we really were pretty good at having a good time. That was part of our life as well – the enjoyment. If we weren’t off doing a ski tour on an icefield for training, we were doing it on our days off. I just feel very, very fortunate to have been part of it all.

SH: Good answer. Are there any legends or stories associated with the Warden Service that you can share? Is there anyone from the Service that stands out in your mind? I remember you telling me a story, and it’s maybe not a legend story but the one about the goose that landed and you had to get it off the highway. Do you remember that one? Is that a good story?

Bob: Oh the swan.

SH: Ya, you don’t have to tell it but I remember that story. (Tape 5:09)

Bob: No that was a good story. I can tell it. Angela Spooner and myself, I was in the Human Wildlife Conflict Specialist role and the other person in the operation at that time working with me was Angela Spooner. And we got a call that there’s a swan in the parking lot in the park administration office. We would get this sometimes, mostly with small ducks where, If it rained, the parking lot would look like a pond and often there was a lot of water laying on the parking lot after a big storm, and a duck would land on it, and then discover that it’s not water and it can’t take off. So in this case it was a swan. The swan is trying to get lift off but just can’t. So we go and look at the situation and it’s very close to the end of the day and the staff are leaving so we just carefully try to herd the swan around the corner from the parking lot into this ditch that has some water sitting in it. And we succeed in doing that and then the staff leave and they’re very worried about this swan. We’re not quite sure what to do either, and the swan does try to take off from the ditch but again the runway is too short and it just can’t do it. So they we go “Okay, we’ll go back to the office and get a kennel” and we had a giant salmon fishing net with a long handle that we’d use for catching birds on the ground, eagles sometimes on the ground injured. So we go back, we got the kennel and it takes a bit of effort but we are trying not to stress out this swan any more than necessary.

But finally, we get the net on it and then we get a blanket over … you know the standard operating procedures. Once the blanket is on, whatever is captured tends to calm down and the swan did. Then we slowly managed to lift it and get it into this giant plastic dog kennel in the back of the truck. It just barely fits in there but it’s okay. We close the door, and it’s there, and so our plan now is to take it to Grice Bay boat launch and let it go on the ocean there. So things are going okay, we’re feeling pretty good. We drive up the Wickaninish Road onto the main highway and by now it’s dark and I turn onto the highway and there’s traffic coming behind me as I pull out. Then Angela pulls out behind a couple of vehicles. So I start down the highway and I’m looking for where Angela is, and I just see headlights so assume it’s her behind me. I’m checking the mirror and all I can see is like when they shine the lantern on the sky in Gotham, with the bat wings. That’s what it looked like except it’s in black silhouette. It’s this giant wing form in the back of the truck with this long neck with the headlights shining behind it. So I go “Holy shit, the swan is no longer in the dog kennel”, so I slowly, just try to slow down very gradually and I’m hoping like hell that the swan doesn’t jump out of the truck while I’m going at speed, and the car coming up behind doesn’t hit it. As I get almost stopped the swan, sure enough flaps out the back and onto the highway and the car swerves and misses the swan. I grab the net and I’m back out there trying to herd the swan off the highway before the other car comes along. So I capture it again and manage to …. And by then Angela has arrived and we repeat the whole procedure. This time … I forget what it was, it was something particular about the latch system and the swan had managed to do whatever to get the door open. But we got it to Grice Bay boat launch and it was one happy swan to hit the water.

SH: I always liked that story. When I’ve seen swans stuck on ice after that story I’ve often thought of you. Sorry I didn’t mean to cut you off, let’s go back to the legends stories. (Tape 12:06)

Bob: Well I told that one about Brian and taking on Ian and me as total greenhorn backcountry wardens. All of those guys were legends in our eyes when we were starting out. It wasn’t just the wardens either. It was also the helicopter pilots, like Jim Davies and Garry Forman and Todd McCready and it was also the dispatchers, like yourself and Scott, Nancy and Oliver from Rogers Pass but you know…. Gord Peyto and all these larger than life figures – like Toni Klettl and Willi and Peter Fuhrmann and Hans Fuhrer even some of the outfitters, like Tom McCready and Buster Duncan. All of those people that were real mentors for us.

All of those people that I mentioned but also like Gord McClain. I heard about Gord, he was legendary when I started in Jasper but he’d just left to start working at Pacific Rim, but by the time I got posted to Pacific Rim I’d been hearing Gord McClain stories for years. He was a living legend and he was a great mentor for Rick and myself and Scott Ward and Dan Vedova. Bob Haney was real instrumental in guiding me – it was him and Don Dumpleton and Doug Wellock that hired me for the towerman/patrolman job. I remember some of the advice Bob gave me my first day of work that I remembered all through my career. Gord and Sharon Anderson really looked out for us young wardens. I’ve mentioned Al Stendie a few times. John Taylor, Bob Redhead (Bob really helped me get my permanent position and inspired me to go North), Larry Harbidge, Therese Cochlin, Brock Fraser, Nadine Crooks and Renee Wiisink were all inspiring Chief Park Wardens and Resource Conservation Managers. I can’t list everyone I worked with or trained with, but I learned from every one of them and enjoyed those times. Others like I mentioned outside of the Warden Service like Paul Anhorn, and Peter Schearer and the Schleiss brothers. There’s so many legends, just larger than life people. Tim Auger of course and then there was Pat (Sheehan). Pat, he was such a great friend and for my career …. for Pat it was his nature, he never recognized a boundary, he was always working over the line at whatever he did. Scuba diving deeper, take off on the bigger wave surfing or whatever it was, and something that he really helped me at… was many times,…I remember times in Jasper going out climbing and he was always pushing me out of my comfort zone. I did things I never believed I could have done if it wasn’t for Pat. He always had confidence and he just knew how to bring that out in yourself. He could make you believe that you could do it. He impacted so many people. The list could just go on and on. Denny Welsh too, there’s a larger than life character. I made absolutely sure that my horses were well fed and well looked after. I knew what the standard was, Denny’s standard and there was no way I was going to run afoul of Denny. In his own way he was such a great mentor. He was awesome. (Tape 18:08)

SH: Is there anything about the Warden Service, as you knew it, that you would want future generations to know?

Bob: As much as things have changed over the years, and as we know in recent years, a lot, I’m really inspired by young people coming on that you can see that they have that same passion for the mission of national parks and that’s what’s encouraging is that they are appreciative working for national parks. That’s what I find really encouraging; that with all the ups and downs, and it seems like often the wheel gets reinvented, centralization, then decentralization and then centralizing again, you know things like that …. I’m hopeful that maybe things will come around again, and there’ll be an appreciation for what we were able to deliver as an organization in the past and maybe we want to try and regain that footing in the future again.

SH: What made the Warden Service such a unique organization?

Bob: It struck me when I was in the role of Human Wildlife Conflict Specialist, how like when the wolves arrived on scene in a super dramatic fashion, and we went from wolf sightings being extremely rare to having multiple attacks on dogs and very intense encounters between wolves and people and I was reaching out to my counterparts in the system like Glen (Peers) and Wes (Bradford) and Rick Ralf, and others as time went on. What other organization would have the capacity to really try and get ahead of the curve on that set of challenges. That there would be dedicated people, not only within Pacific Rim National Park, but within a national organization that are putting their heads together and trying to work out and address these challenges and thinking about it seven days a week, 365 days a year, year after year. What other organization has that capability or that mandate to maintain that level of focus of resources and knowledge and experience in a directed way like that. That’s pretty unique. I don’t know of any other organization that has been able to work in that direct a fashion with that many people at a national level.

SH: That’s a good answer. Do you have any lasting memories as a Warden? Favorite park, cabin, horse, trail, humourous stories, etc. Some of them we’ve done but ….

Bob: That little log cabin at Maligne Lake my first three summers. It was 10 x 10 feet, and I couldn’t think of a better place to start off. I had to get water from the creek and had a wood stove and I was working on that Station with Al Stendie. That was such a blast and a great way to start my career. And Blue Creek … those two summers where I just had so much to learn about everything I was doing and myself but under the careful hand of Brian Wallace and others like Tom McCready and all the partners in the backcountry that worked together; Al McDonald and Bernadette, Norcross, Ian and Jean Stoner and the gang. And again 1984 when I had Brazeau District on the South Boundary with Darro Stinson as the B/C Supervisor and John Kellas in Rocky and travelled a bit with Jane Emson and Rick Ralf as well. Those were pretty special years and it’s something that just hardly exists anymore. Working those 24 day shifts where it actually took you that long to get around your whole district and do a bunch of work. That was pretty amazing.

Then Rogers Pass such an intense place but such great times and people and experiences. Learning how to ski in Rogers Pass on Mount Fidelity. Quite a place to learn how to ski, and all the experiences we had up there. Then working with Bill Laurilla ….here’s a Warden that spent his entire career in two parks and grew up there as well. So I feel so fortunate that I was able to spend time with Bill. He was such a character and he had the stories boy.

Then out at the Rim, with Gord McClain and our crew with Dan Vedova, and Mad Dog (Rick Holmes) and Scott (Ward) and myself … What a gang… teamed up with Gord McClain, that was a pretty fun way to get introduced to the coast. I loved my years working on the West Coast Trail and then several years being the Broken Group Warden. Living and working out of lighthouses, and doing sea bird and whale surveys …. You name it, it was a great run.

SH: Do you have any photos of yourself as a Warden that you would like to donate to the Project, or that we may copy? Do you have any artifacts/memorabilia that you would like to donate to the Project (Whyte Museum).

SH: What year did you retire from Parks Canada? What do you enjoy doing in retirement?

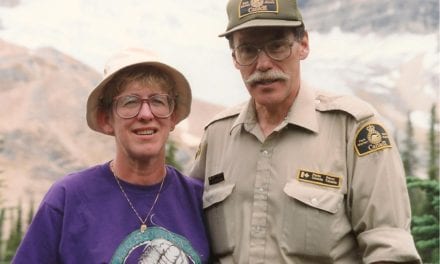

Bob: Well I retired in 2014 and then they hired me back as a term for four summers. Then the last two years, this is my second year as a full time WildsafeBC Community Coordinator for our region. So I work with all the communities and the First Nations out in this region. Ya, so I just get to carry on with the sort of work that I really enjoy.

SH: And you have a lovely and smart bride that you’ve been married to for 30 years and two lovely daughters, so it’s been a good go.

Bob: Yes, it has and they’ve got good memories like your kids … of being at Warden Cabins and those trips.

SH: Is there anything I haven’t asked you that you think I should know about the Warden Service?

Bob: I was just thinking that when I was starting out was around the time of women joining the Warden Service. That was something else that I feel really fortunate to work with those women Wardens that were breaking that trail. I mentioned Jean Stoner, and Bette Beswick, and I worked together at Maligne. And Kathy Calvert … we never directly worked together but Jane Emson and I did some trips and schools with Diane Volkers. They brought so much to the organization and really helped it grow and change as an organization …. That was very cool.

SH: That’s great. Thanks for saying that. Is there anyone else I should talk to? They’re on Phase 10 now, so most of the old guard have been done.

Bob: Gord McClain, Rick Holmes, Dan Vedova, Rick Ralf, Wes Bradford, Murray Hindle,

Gord Anderson and Sharon Anderson were great mentors to a bunch of us. Gord, the always steady hand and Sharon was like the den mother. (Gord McClain, Gord Anderson, and Rick Holmes have been interviewed)

You have to interview Pete Clarkson. As you know Pete is a character and a half and is the master of storytelling. Unfortunately I didn’t get to work with Pete in the mountains but we’ve been a team in Pac Rim for almost 20 years. Too many good stories to even start but will leave that to Pete.

This is such a great project Sue. Thanks to you and the Warden Alumni.

End Tape 31:31

Susan Hairsine

Susan Hairsine worked for over 30 years for Parks Canada in Resource Conservation and Operations in Mt. Revelstoke/Glacier, Jasper and Banff national parks. She also worked for Public Safety in Western and Northern Region. She was also the Executive Assistant to the Chief Park Wardens of Jasper and Banff national parks. During her career she obtained funding for an oral history of Parks Canada’s avalanche personnel. Her experience working with several of the interviewees during her and their careers has been an asset to the oral history project.