SH: So, Clair, we could also talk about some other embarrassing vehicle stories. I also like the one about the road closed gate on the Icefields Parkway with Mike McKnight.

Clair: So, we had taken the helicopter up the Banff-Jasper highway heli bombing in the winter. The helicopter had gone north to go and do the Jasper end as well. So my boss Mike McKnight had driven up in the suburban I was using at the time and picked me up at Saskatchewan Crossing. Now, it had been a big storm but the road crews had been up, and the highway was plowed but there was no traffic because the Jasper end was still closed. So the closure was a gate at Lake Louise. So, I’m driving and looking at the avalanches that we bombed down, looking at the naturals that were coming down and as we’re getting close to Lake Louise I’m looking up to the ski hill to see what had been happening up there because the crews had been working all day, they’d had a lot of good releases. I was really interested to see what was down where. So, I’m staring up at Lake Louise ski hill, trying to see what was going on, and flying down the road at 100 kmh. Everything’s just perfect. Truck’s got good tires, everything’s just fine, but I’d forgotten the gate was closed. Just kind of gaffed on that part, So I come around the corner and the gate is looming up at us, and I hear this sucking sound and it’s Mike McKnight who is sitting beside me, and who realizes I’m oblivious to the fact that I’m going 100 km/h through a locked steel gate. Hit the gate, and luckily, I had a big steel grate and a winch on the front of the truck. The gate flew into a dozen pieces. I hit the brakes and realize there’s really nothing I can do to put it back together again. Mike suggested that we should probably stop and make sure that no traffic goes up while (the gate) was open. Whereupon I promptly got on the radio and called the highways maintenance crew and asked to talk to the foreman and said “Some asshole has just driven through the gate on the Banff Jasper highway. Can you send a welder up to repair it?” (End Section 1 – 35 min 16 sec)

SH: Can you tell me about any rescue/wildlife/enforcement stories that stick out in your memory? Part 2 – Tape 00:14

Clair: Well, the legends were the stories that I heard … that were relayed to me when I was coming onto the service. Probably one of the big ones was the rescue of Charlie Locke off the north face of Mt Babel, which was kind of a technical milestone. Back in the days still of Walter Perren. When Bill Vroom was one of the lead public safety guys and ended up being on the pointy end of the cable. So it was a cable rescue off of the big north face of Mount Babel. A milestone for the time but also something that spurred us to keep our technical standards going, because we realized that things that happened in the past were going to happen in the future. We’d better be ready for pretty much anything. So that’s what we tried to do.

SH: Did you do any rescues in the Northwest Territories, on those big peaks? Did you have to go on any out of Park rescues?

Clair: Ya, ya. We got called to go to Bella Coola. So I was at a meeting with the Provincial Emergency Program in Kamloops. A guy named Ross Cloutier was influential then with the Provincial Emergency Program and he was chairing this meeting. And in the middle of the meeting he got called out of the room. Comes back ten minutes later and looks at me and kind of gives me a nod and a wave to come over and chat with him, and he said “Would you be willing to take some of your guys and go to Bella Coola to take charge of a rescue operation that’s happened up there? We’ve just crashed a military Search and Rescue Labrador helicopter and killed a guy.

SH: Like a pilot?

Clair: No, it was a SAR Tech who was hanging on the cable when the machine crashed. So I said “Sure, no problem. He said “There’ll be a government jet here at daybreak to fly you to Bella Coola. We want you to basically take charge of the rescue until we can get our volunteer teams in there which will be two or three days at least.” So I called Eric Dafoe and Marc Ledwidge and told them what the drill was and asked them to grab the gear that we might need for an extended search on high alpine glaciers in the Coast Range. So Marc’s leaving Lake Louise, he’s got a truck full of gear and he stops in Revelstoke and picks up Eric and drives to the airport in Kamloops and it’s just breaking daylight. And here’s this nice fancy jet sitting on the parking lot with a police car beside it. So Marc drives up to the gate, hits his red and blue lights and gets out and goes to open the gate, and the cop car drives up and the cop says, “Who are you?” And Marc says “We’re the Parks Canada guys going on the rescue. I need to load this equipment into this jet”. The police car backs up, and the window goes up. Obviously the guy is talking on the radio. The police car drives forward up to the gate again. Window comes down a little bit and the policeman goes “Excuse me sir but this is the Prime Minister’s jet. Your jet’s the little one down on the end of the runway.”

SH: That’s funny. So was that Chretien? Clair: No it wasn’t. It might have been Martin. Anyways he happened to be in Kamloops that day.

SH: So you want to finish that story?

Clair: Okay, a long story. We got to Bella Coola, and the SAR techs were sent home to Comox. We took control of the search and did the usual things. We tried to find the most likely locations and did a bunch of very cool stuff. Isolated their most probable location down to a small pocket glacier out in the middle of a huge icefield. We stayed there for four days, the BC PEP (Provincial Emergency Program) volunteer people finally came in and took control and we left and got flown home. But they never found them. A big storm hit and their tent got covered. They were both dead in an avalanche and they weren’t found until August of the next year when the tent finally melted out. They were exactly in the location that we’d determined by using travel time and weather and terrain variables to calculate that. That was fun. I’ve got this great picture somewhere of Marc and Eric sitting in this little jet going “It’s like a jet ranger but bigger.”

SH: So I put that in as an aside. I want more stories …. Robson rescues, big avalanches…. I know you did so many rescues Clair.

Clair: Some of the memorable ones were when things didn’t go as scheduled, or as they normally would. Where we had to step outside of the regular routines. So, I remember for instance going to do a body recovery on Mount Temple and the winds being so turbulent, we just about crashed the helicopter. Jim Davies didn’t want to fly anymore because of the turbulence and we ended up having to take horses up and evacuate a body down from Mount Temple over the back of a horse, after we found him and had to bring him down several thousand feet in a mountain stretcher, and then had to put the body over a horse to take it down to the parking lot.

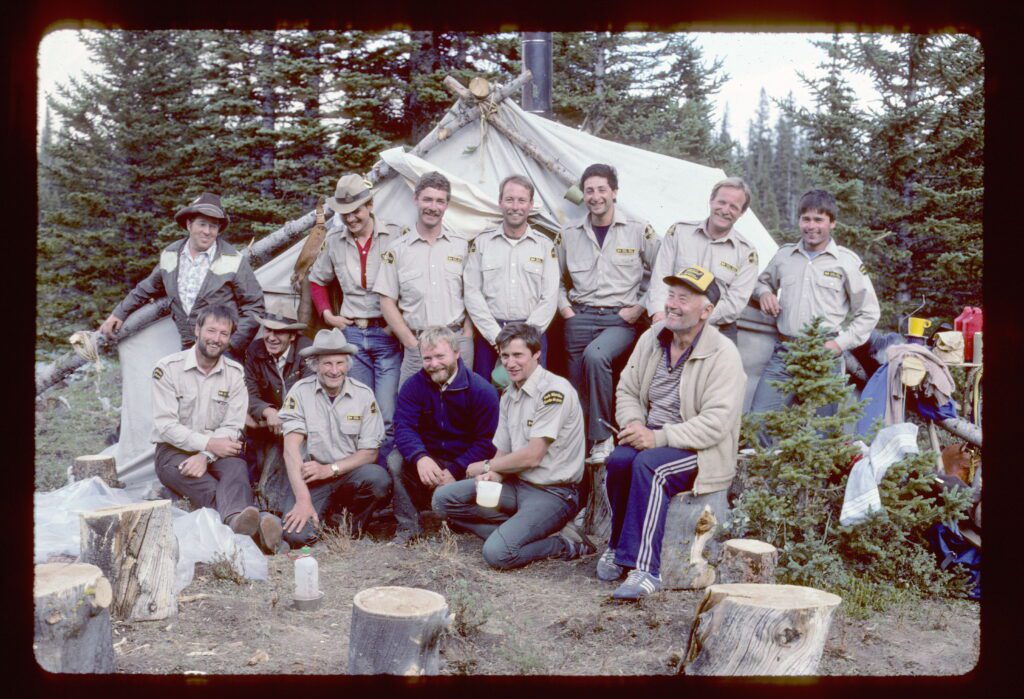

1985 Centennial Climb

Back row: John Nylund, Frank Burstrom (Rev/Glacier); Peter Deering (Gros Morne); Ed Abbott (Elk Island); Ron Tessolini (Banff); Darro Stinson (Jasper); Brent Kozachenko, Waterton)

Front Row: Clair Israelson (Banff); Dale Loewen (Banff); Hans Fuhrer (Kootenay); Tom Elliot (Yoho);

Eric Dafoe (Rev/Glacier); Willi Pfisterer (Jasper). Missing from photo: Don Mickle, Tim Auger, Gaby Fortin.

SH: How did the Warden Service change over the years? Section 2 – Tape 07:46

Clair: When I started the Warden Service was …. they were all older and a whole bunch of them were very very, close to retirement They’d all sit around the coffee table in the Warden Office rolling smokes, because people still smoked in the office at the time. and bitching about the good old days in the district system where they had a very different way of life and now they’d been centralized, and all had to work out of a central office in either Banff or Lake Louise. A lot of these old guys didn’t take very kindly to that. They saw it as kind of imposing on their individualism, forcing them into a way of life that they weren’t used to. And on the other end of the coffee table were all us young kids. We’d all just been hired and had somewhere between zero and a few years’ experience. We thought that it was just fabulous. We were happy with the way things were and didn’t know the old ways. We weren’t maybe very thrilled about living by yourself out in the backcountry cabin accessible only by a horse trail. So, we thought it was great. So there was this kind of generational divide, with a bunch of people who were long term employees who weren’t very happy. And then all the younger folks thinking this is awesome, what a fabulous job and how could I possibly be happier. And I saw the whole thing happen again over the course of my career. By the time I retired there was a generation, it was my generation who were kind of grumbling and shuffling their feet over changes in the structure and how the organization was being managed, and all the younger folks coming in, the young kids who had only a few years’ experience were happy. They thought things were just fine and couldn’t believe we had such a great job and what were we bitching about. So I saw that whole cycle kind of reinvent itself with my generation where we saw a change as something that was to be avoided if possible, but of course that’s not how it works. Things change, old habits die, and new habits form and it will always be that way.

SH: Okay This is a funny story. I want to talk about Lake Louise ski area taking over avalanche control and maybe some bombing stuff that happened there that was kind of amusing…. Maybe with signs or ……

Clair: So In the winter time I ran the Parks Canada … The Warden Service ran the avalanche control program at the ski hill and that continued on until the early ‘90s. In the summer time I’d be involved in the environmental impact and development being the Parks guy kind of on the ground and the first contact with the ski area people.

During I think the late 80’s, the late 70’s, Charlie Locke bought the Lake Louise ski hill and brought his own unique management style with him. There was often a bit of head butting going on between not necessarily the ski hill staff but between Charlie and the Park management team over environmental issues. Charlie built a lift at the back of Eagle Ridge, the Paradise Lift, with the proviso that he couldn’t go in there with a bulldozer and just bulldoze the terrain down because his environmental impact assessment contract had said that basically it’s not a viable thing to do because of problems with erosion and difficulty re-vegetating this big disturbance that would occur. So you can build the lift, but you can’t take a bulldozer in there. (Tape 13:23)

Well the first winter the lift was open everything worked great. People loved the terrain back there until they got down near the bottom where there was this little cliffy break over with a bunch of big sharp boulders in there that was just ripping the shit out of people’s skis as they came by. So it was this great run with this absolutely horrible hundred meters in the middle of it that was damaging everybody’s equipment, and people were upset.

I went back there one day, and I saw this sign had been erected, and this sign had been made by Charlie and it said something to the effect of … ‘We apologize for these rocky conditions. If you’d like to see us fix this that please call …. ‘ And there was an Ottawa address to write to Parks Canada in Ottawa to get the Parks people to give him permission to take a bulldozer down there.

Well I found this really disingenuous, and it really kind of bugged me because this had been a condition that he’d actually promised right from the get go as a condition of approval. So, I happened to be skiing by one day with Mike Gibeau, and we had a spare 5 pound bomb in my backpack and it was still early in the morning, the lifts weren’t going, and nobody was around, and I thought, it’s time to disappear the sign. So I taped this 5 pounds of dynamite onto the sign, lit the fuse, skied away and came back a couple of hours just to check and all that’s left is just a little charred stump, 4 x 4, and everything else is completely gone, just disappeared. So I was really proud of myself.

Well a few days later I got called to the Superintendent’s office in Banff, a guy Jim Volmershausen, who was a great fellow, and as I walk into the office, I’m not quite sure what’s going on, but as I walk into the office and there he is sitting with Charlie Locke and on the desk in front of him is this warped, twisted, blackened, dynamited sign, that you can barely tell what it was. But I knew. One of the snowcats had run into this thing, and the driver had picked it up and brought it back to Charlie. Charlie knew instantly what had happened, (he) had gone to the Superintendent and I was being called to account. So the Superintendent said, “Do you know what this is about?” And I said, “Yes sir.” So he said, “Charlie why don’t you tell your story”. So Charlie told the story about how I was the only guy with access to dynamite around that place, me or one of my crew, that clearly it was something I had done and that I had willfully blown up his property. And the Superintendent asked me to give my side of the story. So, I kind of I explained how I thought it was just bad form to put this sign out there when we’d known from the very get go this was an inevitable outcome, trying to shift the blame in the eyes of the public from Charlie and the ski hill to Parks and our excessive regulations. And the Superintendent sat there for a minute and kind of scratched his head and looked over at Charlie and said, “Charlie, a review of the Business Regulations suggests that this was an illegal sign. For it to be a legal sign it needs to have a little sticker on it that says NPC, National Parks Canada. That was in the Regulations. This sign didn’t have the sticker on it. I suggest that my guy here Israelson was just removing this illegal sign the best way he knew how.” At which point Charlie picks up this twisted piece of metal, puts it under his arm and storms out the door. The Superintendent then went and closed the door and went up one side of me and down the other and made me promise never to do anything like that again. But I got one free pass.

SH: What about the Warden Service was important to you? – Idea of protecting and preserving national parks, keeping people safe, etc.? Tape 19:18

Clair: Oh boy. No, I totally bought into what the mission of what the national parks was. So from the big picture overview of preserve and protect down to the minutia in operational stuff that was going on. Just conceptually the whole thing just appealed to me. I liked the idea of doing something that had some significant purpose in keeping with the Parks mandate for managing the land. It seems I was a good fit for the emergency response part of the service provider aspect of things. I liked the idea of working in teams and I liked the idea that we were scalable and that when the shit hits the proverbial fan that we had counterparts that we could call in to help us, from Jasper, from Banff, from Yoho, from Kootenay, from around the mountain park block.

So that was great that we were all part of a bigger team that was there to back us up if we needed it. I liked the idea that we were part of an inter disciplinary team, and that there were colleagues who were technically very expert in their areas of expertise, whether it was wildlife management or fire management, or law enforcement or whatever, there was this commitment across the board for quality work. That was really motivating. So there were these great folks like Cliffy White, that kind of transcended the entire spectrum of that. Some of us were a little more limited in our skill sets, so we got slotted into one kind of drawer and kind of stayed there, but no, it was great being part of this team of people, that were each in their own way highly skilled. (End Section 2: Tape 22:18)

SH: Are there any legends or stories associated with the Warden Service that you can share? Is there anyone from the Service that stands out in your mind? I’m going to put you on the spot because unfortunately Mike McKnight passed away, but he was so important in my career, so if you have a good Mike story that’d be great, but if you don’t, don’t worry about it. I know he was your boss for a long time too. (Part 3: tape 00:09)

Clair: He was the best boss I ever had. He had a remarkable capacity to get everybody on the same wave length and get things done. He was great with people, much better than me. He was just a natural leader. Like I said he was the best boss I ever had in any organization, and it was my great good fortune to work with him for a bunch of years.

SH: So legends or stories.

Clair: Legends or stories, oh my goodness. Oh the legends …. Working with people like Willi Pfisterer; he was a legend. He had this great sense of humor and had the total respect of everybody he came in contact with, and largely responsible for setting the tone for public safety wardens across the whole parks system. He was a legend. People like Tim Auger; he was a legend.

SH: Got a Tim story?

Clair: Aside from him telling a bar waitress that she was so beautiful that she made his teeth ache? Tim was great. We had different personalities, but we were kind of like the yin and the yang of the public safety program there in Banff. I think we were a great compliment to each other and kept each other in balance. He was great.

SH: Do you have any stories …. This is where you can tell me more stories.

Clair: Well, there’s all kinds of rescue stories but they’re all the same. Something bad happens you go out and mop it up. We didn’t take ourselves very seriously, which is probably a good thing, and we liked to have fun. And we did some things that were absolutely horrible, but they were sure funny at the time. As an example, at the end of the day after working up at the ski hill we’d have to drive down the road from our little office up there at Temple Lodge, back down to Lake Louise and that was right beside the ski out. It would come out from Skoki and this was a highly popular ski trail, so there’d be all kinds of people on cross country gear skiing out, down the ski out on the end of the day. And on a nice spring day occasionally we’d maybe even have beer before finishing our day. So after having a beer, we’d all pile into the truck and sometimes the devil just made us stop on the road right beside the ski hill and watch the skiers come down this icy steep pitch, hit a bump over the bridge at the bottom and then go rocketing down this long, long ski out where you needed lots of speed to make it to the end without having to work too hard. So people are almost out of control and they’re going fast on cross country gear, and it was amazing what would happen if you’d hit the siren as they came by. Amazing blow ups. Mostly they laughed. (End tape 06:07)

SH: So I’d like you to share some stories about the community of Lake Louise and some of the practical jokes. Man, there were some funny stories. (Part 4 – Tape 00:09)

Clair: So the village of Lake Louse was being redeveloped with new Visitor Services facilities and a lot of money was being spent on new buildings and landscaping and all this kind of stuff. We ended up with a new police station, a beautiful new building, and the Parks guy, Swanick, spent a bunch of money taking these beautiful blue spruces and landscaping the police station yard with these expensive trees.

Well it came Christmas time and my neighbor Dale Loewen decided the tree that he’d procured from somewhere along the Banff Jasper Highway, was a little bit too tall for his house, so he cut the bottom off of it. Now we weren’t really supposed to go and get your Christmas tree up the Banff Jasper but we all did. Dale was a little concerned about not wanting to be too blatant, so he was looking for a way to dispose of the bottom of this Christmas tree. So, he put it into his truck one night, drove it down to the police station, walked around, shook all the snow off these beautiful blue spruces that were recently planted there at great expense. Walked around, tracked the place up, shook the snow off the existing trees and then plunked his bottom of the Christmas tree into the snow and left. The police came by the next morning, and what on earth? Somebody had had the audacity to come up and saw down one of their beautiful, decorative blue spruces. What nerve. And they got really pissed off and they were sort of scouting the town to see who had absconded with their decorative blue spruce. They kept the file open until the spring time when they realized they’d been had. It was great. And we never did tell them who really did it.

SH: I like that one. Yes, it seems like it was the place of practical jokes out there. Do you have any other good stories?

Clair: No people are still alive. The guilty are still alive and so are the innocent.

SH: I already have the story on tape of you breaking the smoke detector in the Lake Louise Warden Office when John Steele wanted you to come to a meeting.

Clair: Well that wasn’t nearly as bad as Dale Portman who took it upon himself to try to make John Steele crazy by putting cotton batting into the mouthpiece of the phone and then taking it out, putting it in, taking it out, putting it in…. Some days it would be there and the phone would work and other days it wouldn’t.

SH: Dale Portman, now there’s stories.

Clair: Yes, there’s stories. He was a neighbor for a long time.

SH: Well Clair one thing I want to put down in here, when I came to Banff, you were sort of bringing the public safety program up to speed with computers, and things and that’s one thing I do recall about you. You fought tooth and nail to get computers out at Temple and some of the avalanche computer programs. And the battle with Dave Day over using the fax. Remember we’d have to go pick up the fax machine so we could fax the avalanche control bulletins?

Clair: Ya, trying to move us into the computer age. It was becoming really apparent that there was a place for computers in our operations and that we’d be handicapped if we didn’t have that. And there was the usual competition for resources. So, if you wanted something it had to be budgeted and justified and this kind of stuff and that was the start of it. Now the entire Warden Service is computerized, and all that stuff is taken for granted, but at the time there was nothing; we were entirely in the world of paper and pencil. When we started putting out a backcountry avalanche forecast that would have been in the late ‘80s. Obviously paper and pencil wasn’t going to work. We had to use the technology, faxes at first and then emails to distribute the daily backcountry avalanche hazard forecast. So I worked hard to get that adopted within the Service. It was just sort of keeping up with the times. I’d forgotten about that.

SH: I remember on the weekends we were allowed to have the one fax machine from Dave Day’s (Superintendent’s) office and we could bring it to the Warden Office, but on the weekdays, we had to go up to Dave Day’s office because he didn’t want us to be faxing things he didn’t have control over. It was just bizarre when you think of that now.

Is there anything about the Warden Service, as you knew it, that you would want future generations to know? (Tape 07:35)

Clair: It’s amazing what you can accomplish with all these highly individualistic coworkers when you harness that much energy. It was a very high energy place to work. High preforming people, great people in all of the activities that the Warden Service addressed at the time. Our colleagues, whether they were in wildlife, or in fire, or whether they were in law enforcement or whatever; highly capable people that were a delight to work with because they were cool individuals. And you harness that much energy and you can do a lot.

SH: And you did. What made the Warden Service such a unique organization?

Clair: I think it was our historical link to the backcountry and that earlier history of Wardens being people who knew the land, knew what was happening and felt comfortable to travel and empowered to travel through any kind of park terrain. I think that was kind of the core of what made the Warden Service so special. There was a recognition that you were a member of this club and you were very aware that you shouldn’t be doing anything that would seriously damage the reputation of the uniform.

SH: Good answer. Do you have any lasting memories as a Warden? Favorite park, cabin, horse, trail, humourous stories, etc. (Tape 10:49)

Sure, there’s all kinds of individual events that make up the mosaic, but I think for me the most satisfying thing was the big picture of it all together. This incredible good fortune to be hired straight out of school, green as grass, kid from the city and being invested in by the organization and taught all these skills to the point where I was eventually able to get a mountain guide ticket. That’s all a result of training through national parks. Amazing. And then the ability to work all those years with all those amazing people based out of Lake Louise where it was such a great place to raise a family. We had cross country trails out the back door, we had a ski hill just up the street, there were horses at the barns for us to use whenever we wanted, it was a fabulous little community where everybody knew everybody and just this idyllic way of life. Having an interesting job and being able to work in a beautiful place, surround yourself with the whole National Park life, and being given the freedom to go on training climbs anywhere I wanted. Taking other wardens out and keeping our skills sharp. That … Just tremendous opportunities that I never would have imagined when I was a kid going to BCIT, that I would literally fall into a job that was so satisfying.

SH: Clair, as a bit of an aside, because we talked about rescue, but avalanche control. Can you talk about how Parks Canada got into that and the training? Can you talk about that piece of your career, where that skillset came from?

Clair: The training, we did our in house training but we also sent our people on training that was offered through the Canadian Avalanche Association which was very new at the time. So, it was the CAA that held their week long avalanche schools and we wanted to move as many of our staff through that as possible and did. So that was training that was available to us from an outside source that we didn’t try to replicate in house. Where things that we needed that weren’t available outside, then we’d make them in house.

SH: And Parks Canada was doing avalanche operations on the highways and ski hills in those days.

Clair: Ya, when I first started the responsibilities were avalanche control inside the three ski areas in Banff National Park and then avalanche control for the highways and railways. In the 1980s we felt pressure that we should have been putting up a backcountry forecast because of the increasing backcountry use. The number of backcountry avalanche fatalities that we were experiencing, that we should be doing something on the prevention side there. And there was a reluctance by the senior administration to allow us to put out a backcountry forecast. Their position was basically “Well what if you’re wrong? We’d be liable if you put out a forecast and then it turns out to be wrong.” So, we were having this debate, and then came a weekend in, probably late 1980s when we had four avalanche fatalities in three separate accidents on three consecutive days in the park. I was involved in all of them, and was the Rescue Leader in two out of the three, and then on the Monday morning following this tragic weekend, I was in Banff to be interviewed by some press people and stopped in at the Chief Warden and Superintendent’s offices on the way to the press conference, and the big question was “What are we going to say”. That was the day that the Superintendent and Chief Park Warden said “Well, we should be announcing that we are going to start a backcountry avalanche hazard forecast, as a way of trying to prevent these kinds of things.” So it was a reluctant step forward but now look at what the Parks guys are doing with their backcountry avalanche hazard forecast. They’re world leaders in not just the content, but also the presentation, communication skills. They’re absolutely a top-notch organization putting out one of the best backcountry forecasts in the world. It’s come along ways but that was the start of it. It was reluctantly, foot dragging and kicking all the way, to allow us to do that. (Tape 17:36)

SH: Do you ever miss being a Warden?

Clair: No, it was a time in my life but that’s past now. It was a great, it was fabulous. It was a fabulous job and living in the Parks it was a great place to raise a family, fabulous colleagues to work with, no shortage of practical jokes. There was the occasional beer, but no I don’t miss it. It was a great chapter in a life, but life goes on. I still look forward to meeting old chums.

SH: That’s the nice thing because those opportunities still happen.

SH: Do you have any photos of yourself as a Warden that you would like to donate to the Project, or that we may copy? Do you have any artifacts/memorabilia that you would like to donate to the Project (Whyte Museum).

Clair: I have some old slides and I’d be willing to donate some of that stuff.

SH: What year did you retire? What do you enjoy doing in retirement? I’m never sure you actually retired.

Clair: I took an early retirement I think in 1997 or 1998. I tried the consulting thing for a couple of years. The work was interesting, the money was fine, but I didn’t like the hustle of always kind of working on procuring that next gig. An opening came up with the Canadian Avalanche Association, so I took the job there as the Executive Director. I stayed there for eight years. Then it was time for a change, so I reconnected with an old chum I’d been involved with heli skiing and went and managed a helicopter ski company, Northern Escape Heli Skiing for five years. Got into the heli ski gig as I was leaving Parks and really enjoyed it, loved, it, that was the most fun job I ever had. So I worked guiding heli skiing while doing the CAA gig. So, I got to spend the last five years of my working career going heli skiing and the associated work year round to keep an operation going.

SH: What do you enjoy doing now in retirement?

Clair: Skiing is fun, my body is a bit crocked up, but ya, just to get out in the mountains. Even just to get up high in the mountains. Even drive up to the top of Mount Revelstoke and go for a little walk around the little trails there. It’s beautiful to be up high in a wild place.

SH: Is there anything I haven’t asked you that you think I should know about the Warden Service?

Clair: It’s an organization that continues to evolve and probably always will because the world continues to evolve. The needs change, the politics of the day changes, the public expectations change, and the Warden Service has to continue to adapt to be relevant. So, it’s not going to be stagnant. Over the course of a career we’re going to see significant changes the way programs are administered, and the way the job is done. The technical requirements for staff, educational requirements in particular continue to go up and all of that’s good. Because if we don’t continue to change, it’s evolve or die, so keep evolving.

SH: Is there anyone else I should talk to?

Clair: Darro Stinson

(Darro Stinson was interviewed in Phase 10).

End (Section 4: Tape 24:55)

Interviewer: Susan Hairsine

Susan Hairsine worked for over 30 years for Parks Canada in Resource Conservation and Operations in Mt. Revelstoke/Glacier, Jasper and Banff national parks. She also worked for Public Safety in Western and Northern Region. She was also the Executive Assistant to the Chief Park Wardens of Jasper and Banff national parks. During her career she obtained funding for an oral history of Parks Canada’s avalanche personnel. Her experience working with several of the interviewees during her and their careers has been an asset to the oral history project.

Loved your interview Claire and your great sense of humor. You were bang on about the generational divide that a lot of us experienced early in our careers.. The more that things change, the more they stay the same it seems . Cheers and enjoy your retirement. and, oh ya, I’m pretty sure I can guess who bought the rum bottle and threw the cap away on the road home. Would his initials be JM…. RIP.