Thank you to the Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies for granting permission to the Park Warden Service Alumni to post this interview on our website.

Park Warden Service Alumni Society of Alberta

Oral History Project Phase 10 – Spring 2020

This Oral History interview was funded in part by a research grant received in 2019 from the Government of Alberta through the Alberta Historical Resources Foundation.

In Person Interview with Clair Israelson

March 14, 2020 – 10:00 am Revelstoke, BC

Interviewed by Susan Hairsine

Place and date of birth?

Clair was born in December 1949 in Dawson Creek, British Columbia

SH: Where did you grow up?

Clair: In Surrey.

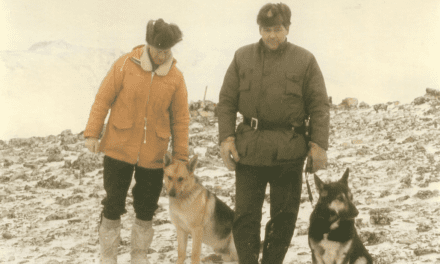

SH: How did you become involved in the Warden Service? Which national park did you start working in?

Clair: I got hired by Parks Canada directly out of BCIT, where I was attending school. They came recruiting and national park was the best job offer I had when I left school, so I took the job, without really even knowing what it was about.

SH: So what National Park did they put you in?

Clair: I started in Waterton in 1971.

SH: Was that a term summer job?

Clair: It was a seasonal job, I spent the summer there and then I was sent to Yoho Park for the winter to work on the avalanche program, such as it was at the time, and then back to Waterton for the second summer, so the summer of ‘72. And then in the fall of 1972 I was hired full time and posted to Banff.

SH: So in Banff were you a generalist warden when you went there full time? Clair: I was already being kind of fast tracked into the public safety stuff. The spring of ‘73 was the Mount Logan expedition and I was the greenest kid on the block, and somehow I got picked to go on that. They put me up at Sunshine and occasionally at Norquay doing the avalanche stuff there, and by the summertime I’d asked for a transfer out to Lake Louise. So I was working there and largely in a generalist role but being groomed for the public safety side of things.

SH: What made you want to join the Warden Service?

Clair: I didn’t really know what to expect coming in, but what I found was there was a generational change going on and there were a bunch of older fellows who were facing retirement and they didn’t like to walk, they didn’t like to hike. And so when I got to Waterton they said “Sorry but you can only drive your truck around one day a week and the rest of the time we want you out on the trails and checking fishing licenses at the high lakes and that kind of stuff. So, you’re going to have to hike”. I thought I’d died and gone to heaven. I couldn’t believe that they would pay me to do that kind of stuff. I fell in love with the job right off the bat.

SH: What different parks did you work in? How did they compare? Do you have a favorite?

Clair: I worked in Waterton, and Yoho and Banff, but very quickly asked for a transfer out to ‘Lake Louise National Park’ because that’s where I saw the greatest opportunity for me to be involved in the public safety stuff that existed at the time.

SH: Oh, you forgot the ‘regional office national park’.

Clair: Oh, that’s planet five.

SH: How do they compare, not planet five.

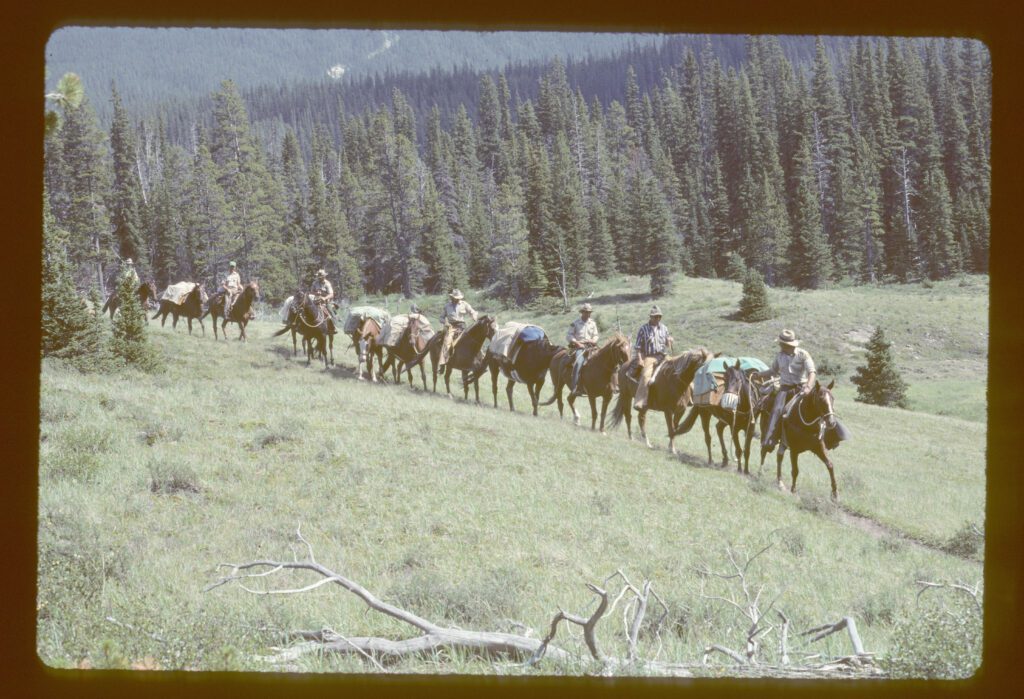

Clair: Oh they are all different and they’re all great. I really enjoyed working in Lake Louise. It was a beautiful place, with a small town community. We had a good enough house that we rented from the government and good neighbors. I really enjoyed the work there. In the winter time it was avalanche control at the ski hill and in the summer time it was the rescue stuff and the training for that of course. And I also got tasked with looking after the environmental development stuff at the ski hill in the summer time. So that was a nice mix. Earlier on in my career I did do a couple of summers of backcountry patrols, horseback riding the trails in Lake Louise. Cyclone and the Lake Louise backcountry. That was absolutely fabulous … I just never really knew what I was supposed to be doing out there other than riding around and burning firewood.

SH: What were some of your main responsibilities over the years?

Clair: With the retirement of the older warden cohort, very quickly I got fast tracked into the mountain rescue, and avalanche control side of stuff. That kind of got thrown at me whether I was ready for it or not.

SH: By Fuhrmann or how did that come about?

Clair: Yes, Fuhrmann, the Chief Wardens and the area manager at Lake Louise. It just seemed that they were looking for young guys who were willing to do that kind of work. Of course whether you liked it or not, if you were a younger warden you got sent out on training schools and ski trip route marches and stuff like that, trying to improve our backcountry travel skills. So it was a major emphasis of the Warden Service in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s.

SH: So that was one of your responsibilities, the public safety side. What other responsibilities did you have over the years?

Clair: Over the years? Oh my goodness. Later on in my career it seems that I was being put on to different types of working groups that were addressing different issues that were facing the Warden Service at the time. Things like cost recovery for search and rescue initiative. And then, at the end of my career I took a job with regional office, as the public safety specialist for western region. That got me involved in a lot of national initiatives. Initiatives around prevention programming for public safety and multi-disciplinary working groups that were involved in all kinds of different things that affected us. Things like working on regulation changes for heli sling rescue and stuff like that that was outside of the operational sphere but still relevant to the overall success of the programs in the Parks.

SH: And you were very unique in this…. Do you want to talk about NSS (National Search and Rescue Secretariat) and the Avalanche Association and some of the other things you were spearheading?

Clair: I got involved with the NSS stuff because they were a funding source. A federal funding source that had money to give away for things that we wanted to do in Parks. So that was a bridge there that got built and maintained for a bunch of years. And carried on after I left Parks.

SH: There was a ton of money in those initiatives.

Clair: Oh ya.

SH: What did you like about being a warden? What didn’t you like about being a Warden?

Clair: I liked the action. There was always something going on and if there wasn’t something going on, you’d make something up. There was no sense of boredom on the job. That was great.

What I didn’t like? I really didn’t enjoy having to deal with the families of people who were victims of mountain accidents. That was really hard.

SH: What are some of the more memorable events of your Warden Service career?

Clair: Some of the memorable rescues were pretty amazing. Probably the most amazing was the Ferris search on Crowfoot Mountain, up from Bow Lake. This guy was out on a scramble up Crowfoot Peak and didn’t come home at the end of the day. He’d left a route description of where he was going with his wife, which we got from her and started looking. We looked one whole day and didn’t find any trace of the guy. We looked …. The second day we pulled out all the stops. We brought in all the dog masters, a couple of helicopters, all of our top search people …. You were there helping with the management of it all. And it was late October and there was a big storm forecast to move in. So this is our last day to search. This big black cloud is sort of oozing overtop of the glacier and coming down and affecting our search area.

Through an incredible stroke of good fortune, we located the guy. One of our search teams located the guy in a crevasse at dusk, just as the first snowflakes of the winter were starting to fall. We found this guy, hauled him out alive, he was entirely okay and that night it snowed about 30 cm and he would have been lost forever. He’d spent two and a half days standing in the bottom of this crevasse, watching us fly over him and not seeing the hole that he’d made in the crevasse where he’d fallen through. That was the most incredible good fortune that I can recall. It was like wow, we actually found this guy, saved a life for sure. We would never have found him, and it would have been years and years before he melted out of that place.

So that was a pretty amazing search. And the amazing thing about it, was the search worked because we had good incident command practices at the time, that included assigning probabilities, assigning teams to a specific area, debriefing when they came in at the end of their day. We had good practices whether it was search management or first aid or all the different …. the professionalism of the public safety programs increased dramatically over the time that I was there. When we started out we were pretty basic and didn’t have much formal training in the how to do things. But some of the major advances …. They put us all through advanced first aid training, and that certainly helped in terms of our ability to provide care for people who were injured. We had Incident Command Training for managing these emergency events. That was a big step forward. What else were things that happened that really moved the program forward?

SH: Well the rescue pilots.

Clair: Oh ya, the Rescue Pilot Testing Program …. Ya, that was a big thing too, to ensure that our rescue pilots met a standard for proficiency and judgement so that was a big deal. And then we just gained experience over time too and that just gave us more confidence that we knew how to respond to pretty much whatever happened. (Tape 17: 48 Section 1)

SH: Clair, as an aside, because this was a huge part of your career, the training., do you want to talk about training and some of the teams?

Clair: Well, there was two kinds of training. There was formal training that was done at a sort of regional level, and then there was a lot of local training. I couldn’t believe that they would pay us to go out and go climbing with various members of the team, and we built up a pretty highly skilled team over the years. With a bunch of people who later on went on to become mountain guides, and leaders in the whole mountain community. There were people like my brother Gerry, Marc Ledwidge, Gord Irwin. Who else was in there that went on to be a guide?

SH: Pat …

Clair: Yes, lots of guys started in the guides training and hadn’t yet completed it. But out of Lake Louise we turned out a bunch of really highly skilled mountaineers and I had the great good fortune to be part of that. I finished my guide training, I got my mountain guide ticket in 1982, and then went onto train and mentor several others that kind of followed along in that track.

We also used horses for a rescue out of the Death Trap out of Mount Abbott. I’ll never forget Jack Woledge in the middle of the night, hoofing up the trail with a string of horses carrying rescue equipment because it was dark, and we couldn’t fly, and we didn’t want to have to carry it all that far because it was heavy. So that was pretty cool using old style tactics for mountain rescue.

There was a few big rescues. Probably the coolest rescue was the cave rescue on Mt Robson where we got called in because Robson didn’t have the resources to pull off an operation of that magnitude. We ended up flying in cave rescuers from all over B.C. The BC Government jets flew them all into Robson. They led the work underground …. had to go down I think almost a mile to recover a body. Parks got called in to be the lead agency. I was there as the Incident Commander because I was terrified to go underground. I was up on site and this guy comes squeezing out of the mouth of the cave, and he’s covered in mud, he’s just filthy. And I asked him “How’s it going down there?” And he said, “Oh pretty good, we’ve almost got him up. We’ll get this wrapped up today.” So, I’m talking to this guy and I finally asked him “You’re probably from BC someplace but what’s your name?” And he looked at me and he said “Marc Ledwidge.” He was so filthy, so completely covered in mud that I didn’t even recognize one of my best buddies.

SH: That was Ric Black, that rescue, where he broke his femur. He was my dive buddy in Jasper on a dive course.

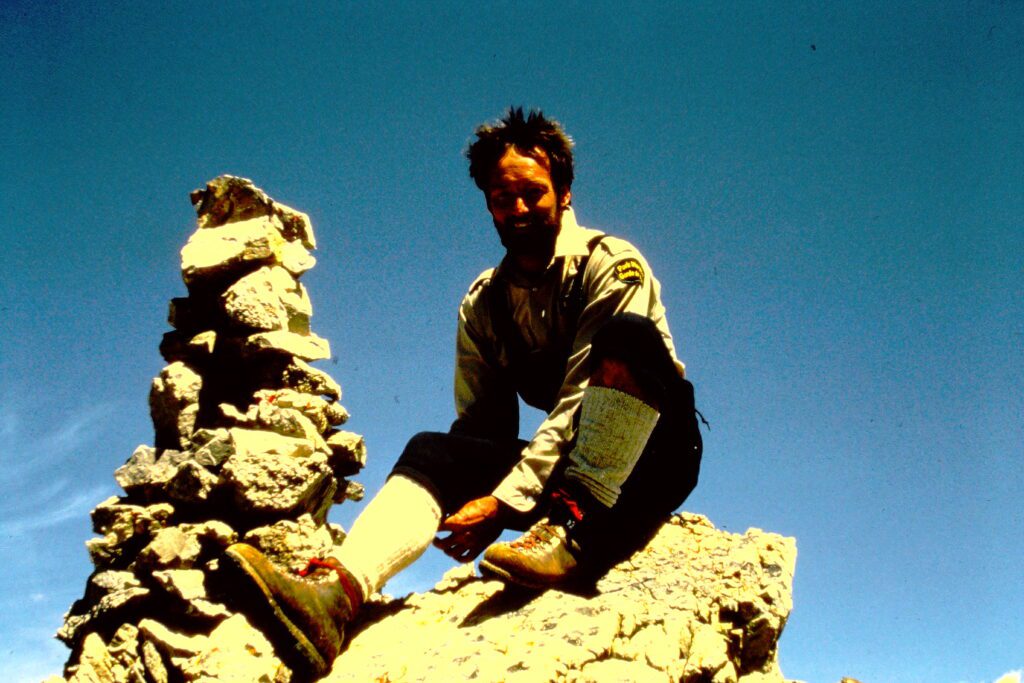

SH: Good story. Logan – want to tell a Logan story?

Clair: Oh Logan that was just an ordeal. My God it was just like a camp out in a storm for a month.

SH: What year is this? Clair: Oh 1973.

SH: So this is when you were climbing Logan or a rescue story?

Clair: No this is the Mount Logan training climb in 1973, when I was just a kid. It wasn’t all that funny, it was basically just survival. We got to King Col at about 15000 feet. And then this storm hit, and it just didn’t stop for month.

SH: Who was with you on that?

Clair: There was Willi Pfisterer, Max Winkler, Hans Fuhrer, Bob Haney, Peter Fuhrmann, Abe Loewen from Jasper. I can’t recall all the details. I was definitely the kid. For me it was an opportunity to see the character of the people that were in the outfit at the time. I felt like I was surrounded by legends.

SH: I just meant Logan in general. I didn’t know about that.

Clair: I was only on Logan once. That was my only trip to Logan. I was on different peaks up in Kluane but only to Logan once.

SH: Did you guys make it to the summit on that trip?

Clair: We bailed after a month. We took food for a month. It may have not been exactly a month, but it was damn close. (Tape 26:35 Section 1)

SH: Other stories?

Clair: I can’t tell them.

Clair: Well, there was drinking. I’ll never forget we got called into Banff, when I was stationed out at Lake Louise, and we got called into Banff for a meeting with the Chief Warden and the Chief Warden was basically trying to lay the law down. He was suggesting that maybe some of us weren’t quite as motivated as we might be. So this particular meeting became known as the thieves, liars and slackers speech. That was back in the days when they were just moving out of the district system, and gasoline would disappear into thin air. So anyways we went and attended this particular meeting.

SH: Who was the Chief Warden?

Clair: The Chief Warden at the time was Andy Anderson who was a great guy. I have a ton of time for Andy. Anyways, this meeting wrapped up at lunch time and we all went for lunch somewhere, and now it’s time to drive back to Lake Louse. We’re three to a truck, and I’m the kid so I’m sitting in the middle. So as we’re ready to drive out of Banff, the driver of the truck who will remain unnamed, makes a quick turn into the liquor store parking lot, jumps out and comes back with a bottle of Captain Morgan’s rum. As we’re driving over the railway tracks, back towards Lake Louise in a government truck with red and blues on top, three wardens sitting side by side by each, very cozy in the front seat. He rolls down his window, grabs the bottle of rum, takes the top off and throws the top out the window. And we proceeded to drink this bottle of rum all the way back to Lake Louise. By the time we got to Lake Louise it was gone, it was empty. I had a hard time explaining to my wife how I came home from work tipsy.

SH: I want you to talk about, because this was a funny story, when you put your red and blues on and the sheep that you hit….

Clair: So, I was driving this 4×4 truck with red and blues, Parks Canada all over the doors. This was back when the highway hadn’t been fenced and twinned yet. So I’m coming out of Banff, just coming up on the shoulder of Mount Norquay and there’s a sheep jam. The sheep had come down for the sand and salt on the road and there’s hundreds of tourists that are stopped and they’re milling around, taking pictures and everybody’s locked in on this group of sheep that are there. I come driving by and I slow down, I’m going quite slow but out from between two cars jumps a little baby sheep. Just a tiny little thing and it went right under the tire. And I thought “What am I going to do?” so I screeched to a stop, jump out, go walk out behind the truck and there’s this dead sheep. What can I do? I know you can’t leave a dead animal in the back of the road, so I threw it in the back of my truck and drove on to the absolute shock of all these bystanders. Were they expecting me to stop and do CPR? It was as embarrassing as hell.

Loved your interview Claire and your great sense of humor. You were bang on about the generational divide that a lot of us experienced early in our careers.. The more that things change, the more they stay the same it seems . Cheers and enjoy your retirement. and, oh ya, I’m pretty sure I can guess who bought the rum bottle and threw the cap away on the road home. Would his initials be JM…. RIP.