MH: What did you like / Dislike about being a warden? 1824:

CW: I liked it from the very first day I got there. I remember it was June 13th, 1975, and I remember coming up to the Lake Louise Warden Office and I was all dressed up in my new uniform and outside at the bottom of the Warden Office stairs I met Traf Taylor who was going to be my full time Warden supervisor. I had on my new Stetson hat and felt pretty proud and all dressed up. As we were walking up the stairs, I noticed a quarter sitting on the top stair and started to bend over to pick it up. Traf just grabbed me and pulled me back and said, “Don’t touch that quarter!” I went, “well why not” and he said, “don’t worry about it, just don’t touch the quarter”. We walked in the door and I met the whole crew there. There was this one Warden standing right by the door that seemed to have a plan (everyone working in Banff in those days might guess exactly who), but anyways, handshakes all around and I realized I was meeting some of the neatest people I’ve ever met here, a bunch of real characters— Traf, Jim Rimmer, Dale Loewan, Larry Gilmar, Jay Morton, Jack Woledge, Judy Reich, Jim Murphy, Scot Ward, Darrel Grams, Clair Israelson, and Paul Kutzer. After formalities, we were all sitting having coffee when this big tall American guy with a bald head wanted some information, and walked up the steps to the office. He noticed the quarter sitting on the stairs, and naturally bent over to pick it up. The warden who was still been standing by the door the whole time now flings open the door, and this poor guy gets hit in the head, flips back down the stairs and does a big roll out onto the dirt. The Warden runs down the stairs and says, “What were you doing there bending over by the door?” Of course, the poor guy probably couldn’t remember what he was doing bending over there. Anyways we got him up and dusted him off and gave him the information he wanted, and sent him on his way. That quarter was actually epoxied to that stair and one or two times a summer when this Warden decided it was time to tune up somebody, he’d stand by the door waiting for them to pick it up, then fling open the door. As my introduction to the office, he had been planning to ruin my new Warden Stetson! I realized this was a great group of people with a great sense of humour. And as the years went on, we fortunately ended up with some more really interesting ladies mixed up with the crowd. As Clair Israelson once said about Diane Volkers, “She is by far our best man!”

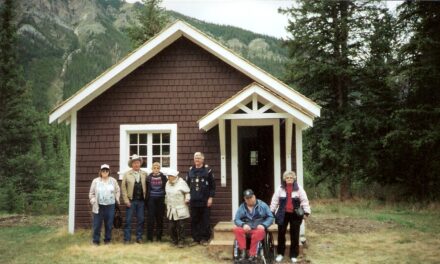

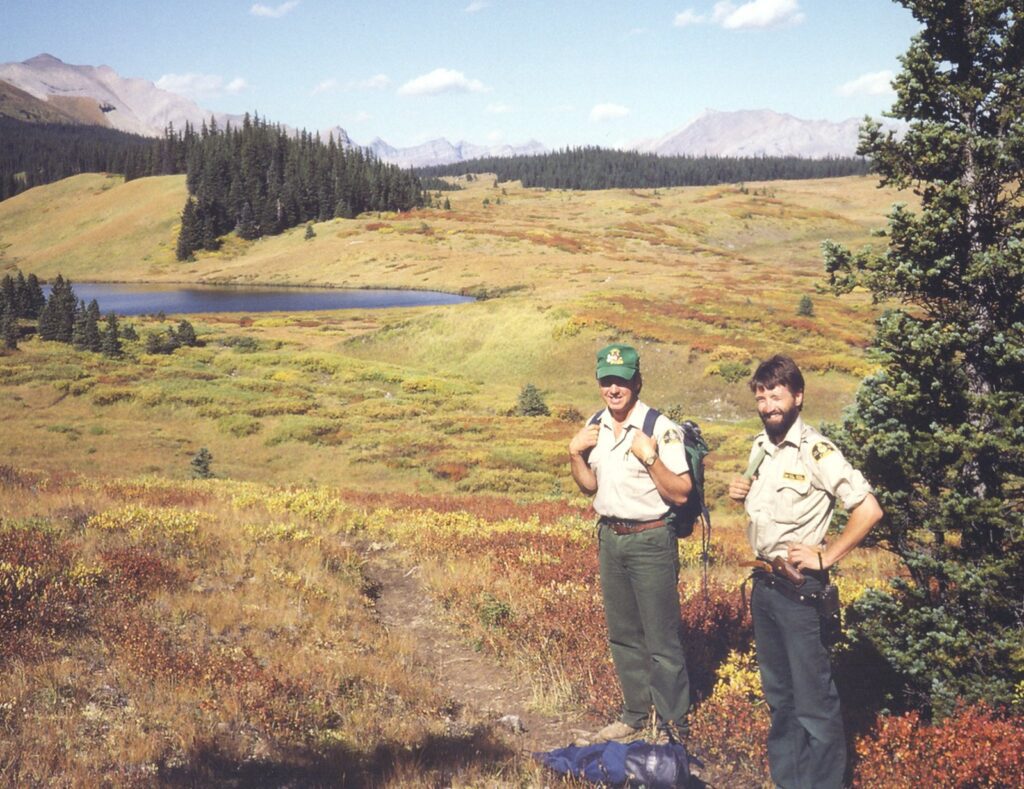

2115: In Banff, everybody stayed so long and we had those really nice rotational shifts and we would meet everybody in the backcountry and everybody had the same skill levels and did many of the same things. Over the course of about 20-30 years, we had basically very little staff turnover. Everybody that came either stayed for 10 years, or their whole career and everybody realized there were times when you had to all work together and there were other times where you would be on your own. Everybody expected a pretty high standard but it wasn’t a place to start kicking the door in all the time, it was a place to just get to work and do a good job. I think we had a really great group of people. As time went on we began to specialize and become more separate in our own specialties but I think with big rescues or searches, everybody still went back to that basic set of camaraderie and work together. Big fires and prescribed burns was another task where we could always muster a crew of 20 people who were darn good at what they did. Everybody knew how to work around helicopters, horses, or even hand-charge avalanche explosives. In the 1990s when we started in the Resource Management shop, we needed to bring in a bunch of young Master and PHD students. We would assign them to work with backcountry wardens. These were people like Dave Norcross, Brian Low, Tom Davidson, Diane Volkers, Glen Peers, and Ron Leblanc, Helene Galt, Blair Fyten. most of whom were in their 30s-40s by then. They really liked to grab hold of some young person doing a research project in the backcountry and take them out and show them how to work with the horses, how to get around the backcountry, how to use the cabins. It was great to have this great team of people where you could take some kid from the city that might even actually be a bit of a dud when they first got there, but when you sent them out for 3-4 months stint in the backcountry doing some research with a veteran Warden, they came back a changed person in terms of how they understood the park, or even how they understood horses. You can learn an awful lot about an ecosystem looking between two ears of a horse– they see a lot of things you don’t see. Most of those kids turned out to be really good researchers and a lot of them went onto some pretty good jobs around Canada and United States.

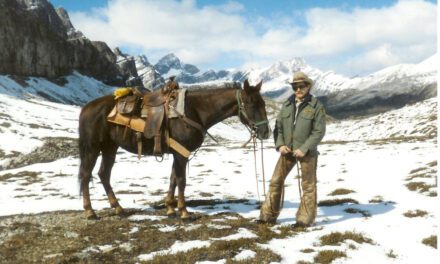

2340: I liked the freedom of being a Warden. Once you got to a supervisory position, it was amazing. In those days in Banff, we managed the whole park and there was always something that needed done somewhere. You had the freedom to make a schedule every year and say, “well sometime in the next few months we ought to check out this part of the Howes River or we ought to get up the Alexandra, or we got to get down to the end of the Clearwater and look at that”. It often just depended on the weather and helicopter time availability. Then in the fall you had to get on the horses to get out on the boundary. So just the whole freedom to do a variety of jobs. And in terms of research, we had ecosystem management problems that were incredible. Working on the TransCanada Highway and figuring out what to do with the animal crossings, how to restore the wildlife movement corridors around the town; trying to get prescribed burns done; the Eastern Slope Grizzly Bear Research Project, Central Rockies Wolf Research Project, Native Trout Restoration, and a major elk population reduction. These were all really interesting and there was no end in terms of academic challenges. I went back and did a PhD later on in the later 1990s because you could just follow that freedom of doing the research that needed to be done. There were tough problems here and they needed to be solved. There was very little you could say that was negative about working there, that’s for sure.

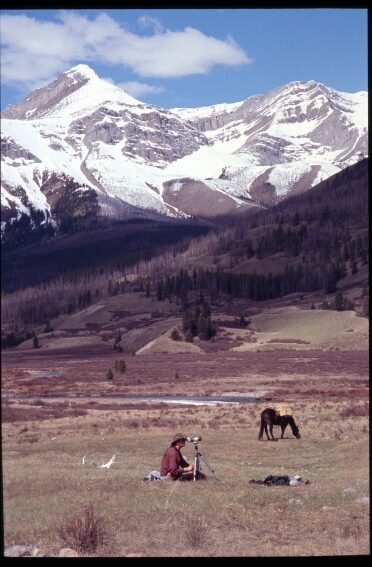

For my doctoral research, I worked on the long-term linkages between humans, predators, elk and aspen. We first started doing prescribed burns in the early 1980s to restore aspen forests. We hadn’t had any young aspen stems in Banff growing since the early 1940s when the elk population went up. But there was this theory that if you did enough burning, you’d create so many young aspen suckers that the elk wouldn’t eat them all and they would grow back. By the early ‘90s we had done a heck of a lot of burning but we hadn’t been able to burn big enough or hot enough to get any young aspen to sucker back. The elk browsed them all off. But once the wolves came back to the park, we did see aspen suckers starting to grow higher so that gave the idea that historically there were few elk, and this was partially caused by wolves, and probably historically more importantly, caused by First Nation’s hunting and burning. This kept elk numbers low enough, caused elk behaviour changes, and the burning stimulated enough suckering so that aspen could thrive. In 1998 I went back to school, and did a PhD looking at 9 watersheds from the north end Jasper right down to Waterton with variable elk densities, variable prescribed burning and disturbance regimes, and variable wolf densities to see what was the right mix to grow aspen back. That required 5 years of part-time field work. I did most of my research in the spring. We had a nice group of people to work with, and headed out to visit some beautiful wildlife winter ranges every spring, usually in May, just before mosquito season. We walked miles of transects counting up elk pellets, wolf scats and thousands of aspen suckers. It was a very simple methodology but it allowed us to figure out what the magic formula was for bringing back aspen stands.

2702: I guess there was some frustration, particularly near the end of my career with the government. when the whole bureaucracy of Parks Canada started to lean on us making work difficult. And it wasn’t just Parks Canada itself. The government of the day decided they were going to be down on science, down on civil servants, and they just created so much paperwork and craziness and I found out for the first time that the government could really be a horrible place to work. One day I was talking to Kevin Van Tighem, the last Superintendent I worked with, and he was having to get a letter of approval from the regional director just to travel to Canmore for a lunchtime meeting with the Mayor of Canmore! In those days I still had all these Master degree students strewn around UBC, University of Alberta, University of Montana, and you were supposed to attend committee meetings. As the bureaucracy tightened up, I went from having standing North America travel approval where I needed no pre-trip approvals, to a new situation of not even being able to officially leave the park to visit students at their universities. I spent a lot of money just traveling on my own using my own car to get to meetings I was required to attend as an academic committee member. I was thinking “this is absolutely insane what the government can be when it really wants to be that way”. It reminded me of when I first started with Parks Canada, the silverware in the warden cabin had initials on it and one of the assignments in those days was to go out and count the silverware to make sure nobody had stolen any from the cabins. But that was the military thing that came in after the war and all the regimentation after the war. Then we started to see that sort of thing come back after 2005. We were now all part of that type of super-bureaucracy where you don’t even think about being creative without having someone approve it for you. That’s disappointing when the government wants to be that way and it doesn’t allow the latitude for people to be the best in their jobs.

One example of super bureaucracy was the change in the computer management systems. When we first got the computer systems in the 1990s, Banff’s computer manager Greg Thompson created the O, or “open drive” and if you signed up as a volunteer or researcher, we kept most of our resource management files here, and everyone shared information on that drive, and really used the computer systems to a maximum. But when I left, just to get a Parks Canada account and password there was tons of bureaucracy and the idea that you might let researchers share information about the Park openly, was no longer thought to be useful. It’s hard to do science when you can’t openly share databases and information anymore.

MH: What were some of your more memorable events as a Warden? 3100:

CW: Well I was lucky enough to do some amazing things. I remember one spectacular day– beautiful and sunny. A couple of fellows were up on the North face of Mt. Bryce and one of them was hit by a rock and had a broken arm and the other fellow took four days to get out to the highway and get help. We started a massive rescue operation to find where this fellow was on face and then figure out how to get over to him because we were just at the edge of what a the 206B jet ranger helicopters could reach for elevation. We were at about 11,100 feet. Anyways, that was a spectacular day where about 8 wardens got up on the north face of Bryce at about 10,000 feet and then managed to climb up and get about level with him across the face. Clair Israelson was our rescue leader. Jim Davies was the pilot and had gotten all of us up there and then he had to take his machine back in for maintenance. Garry Foreman came up from Valemount and helped finish the rescue. Clair and I managed to get across the north ice face to this fellow and we got him in the stretcher. Garry got in with the sling rope and managed to sling him out solo to the meadow about 6000 vertical feet below. Clair and I sat up there on this beautiful day looking across at Mt. Alberta and Mt Columbia and eventually the helicopter came back and grabbed me next. Garry said, “Oh yah, when you get down there you’ll have to chase that bear away” and sure enough, I get down there and here’s this poor guy strapped into the stretcher bag and it’s really hot in the meadow and there’s this bear sniffing around the meadow wondering what this orange bag is. I had to chase that bear away and got the poor guy out of the stretcher to cool off because he was very hot in there. So that was an amazing beautiful day.

Many of us had a lot of good trips with Clair Israelson and Tim Auger over the years– training trips up on the Icefields and we did some awesome ski traverses. We had many good days of burning too. As part of the prescribed burning plans, we needed to burn the guards on nice days in the spring or late fall. It was a 2-4-person job where you got landed with a 5 gallon can of fuel and the pilot takes off, and you are all on your own gently burning these slide paths, working with the wind to burn them out. It’s amazing how much fun it is to work with fire in the valley all by yourself, where you are just gently trying to put in some guards and working up against creeks and trails and avalanche slopes, and really carefully getting that guard in place. And then you’d come back in a few weeks later with the ignition system and light the big burn. Brian Wallace from Jasper, and Mark Heathcott working out of where-ever he was stationed then were with me on some of those “free-roaming” guard burning days. We even scouted a lot of those burns on horseback on fall trips. I’d get out with Ian Pengelly, Brian Low and Tom Hurd, Mark Heathcott or whoever, and do a 5 or 10-day horse trip and plan how we were going to burn various valleys. Those were some beautiful Indian summer days doing that. A lot of good trips!

1992 CW on Ptarmigan Peak: My brother Brad takes an award-winning photograph for the Patagonia Catalogue.

2004 Panther Valley: Mark Hebblewhite from University of Alberta, and now a prof at University of Montana doing his wolf study. Tom Hurd and I packed traps and supplies in for him all that spring.

1992 Elkhorn Summit: Brian Wallace comes down from Jasper to plan some bigger burns.

3447: Public Safety wise, one of the better trips was with Tim Auger in 1986. It took 3 days in January to get into some waterfalls in Marten Creek north of Mount Willington at the north end of Banff Park. We had to go from the Banff-Jasper Highway, over a bunch of passes into the upper Clearwater Valley and then turn and go up Marten Creek. We actually took hand charges with us to get over one of the cols, and bombed the slide path to get down it. It was -40 when we climbed that waterfall. The ice was so cold it shattered as I was leading a pitch. Off I came, and landed on the ground right beside Tim. The rope just caught my last piece of protection as I came down. Tim mentioned quietly, “This might not be the kinda place you want to do lead falls”. I had to agree! Anyways Tim finished it off and we got that route done. Then we had to ski out of there, another 2 days in a blizzard– a great trip with Tim. A lot of good climbs with Tim over the years, especially waterfalls. “Scotch on the Rocks” named by my brother Brad was another classic. Tim made sure that just about every waterfall in Banff got climbed by some group of Wardens over the years.