SH: From there, Perry came to Banff but I’m trying to remember who was the Chief in LLYK then?

Ed: No, lots of things … like I said this is how much change was going on. When they formed the field unit of course they had extra people. Paul Kutzer had been the Chief in Yoho, but that was about the same time he had his heart attack, so he was off on sick leave. So it opened the space up and they put Perry Jacobson as the acting Chief of the field unit. We had two backcountry managers, Terry Winkler in Yoho, myself in Kootenay. I guess we had three because we had Abe Loewen still ram rodding backcountry in Lake Louise.

SH: Dale Loewen? Dale or Abe?

Ed: Sorry Dale Loewen. Dale was there and didn’t really want to have anything to do with us. Of course this was when everything was so new, nobody really had a plan of how all this was all going to fall out. As it turned out Banff took most of their staff and gear out of the Lake, Terry lateraled at some point back into Jasper and I was left as the acting backcountry manager, and Perry was the Acting Chief, but all of these things as acting we knew had to have….there had to be competitions run. One of the first things that happened is they ran the Chiefs competitions. We kind of all knew, you know the scuttlebutt goes pretty quick around the Warden Offices, so before the competition even ran, I think everybody knew how the jobs were going to fall out. It fell out just like everybody thought.

Bob Haney was the Chief Park Warden in Banff but he had announced his retirement. Perry ended up placing number one, so Perry Jacobson got to go to Banff to be the Chief Warden in Banff. They were still calling them Chief Wardens at the time; they weren’t Managers of Resource Conservation. This opened up the Chief’s job in the Field Unit of LLYK. Everybody knew that Paul Galbraith in Jasper, was getting near the retirement age, and that he wanted to retire in the Columbia Valley, so Paul Galbraith came down as a lateral to LLYK to be Chief Warden, which then left an opening in Jasper. We all suspected that Brian Wallace was going to be the Chief of the day, and sure enough, Brian Wallace got to be the Chief Warden in Jasper. The next guy on the list was Ian Syme, and there were no more Chiefs jobs. I believe at the time Ian was the backcountry manager in Banff full time, and I had competed, but I never placed high enough on the list to get a Backcountry Manager’s job. I believe the competition ran and I think it was Dennis Herman was first, Gord Antoniuk was second and I think that Al Mac (Al McDonald) might have been third and I was fourth. So I was left sort of sitting there, going “Okay what am I going to do. I’m a GT04 without a job really.” There was some talk that maybe I could get a job in Lake Louise as the Operations Manager, sort of looking after Law Enforcement as it was, and sort of day-to-day operations. But I was kind of going “I would like to take control of my own life rather than being something bobbing on the water of Parks Canada.”

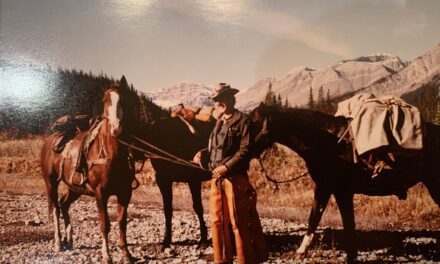

Ed Abbott at Maligne Lake

When I took the Kootenay Backcountry Managers job in 1993, I had discussions with Paul Galbraith and Bob Haney, who was the Chief at the time in Banff, that I had my reservations about going down to a smaller park, and both Bob and Paul said to me “If you hang in there for 4 or 5 years, if you want out, either one of us will give you a job back in our Park.” So, I thought “that’s a pretty good deal.”

So here I was, the guy floating around as a GT-04 so I called Paul Galbraith, and I said “Paul I’m calling in a marker. You offered me a job if I ever wanted to leave Kootenay. This is kind of the position I’m in now. I don’t really have a job. I know I’m not going to lose my employment, because Parks Canada would look after me, but I would like to go where I would like to go. I said “You have a position open at GT-04 level in Jasper”… I guess they called it the Cultural Resource warden or the rotten cabin warden, and I said, “I want it”. So he said “Okay you can come back and I’ll put the stuff in so you can lateral back to Jasper.” So that’s what I did. I left the LLYK Field Unit in 1998, in the summer and I moved back to Jasper.

SH: So that was the first Cultural Resource Warden position up in Jasper, correct?

Ed: Yes, I think a lot of the jobs had been formed but they had actors in them. Donny Mickle was the guy in Banff and in

Jasper, it had been Rod Wallace. He’d been acting in it. As it turned out, I asked for the job, but they gave it to Rod Wallace because he could do the job far better than I could. He was interested in that. I was just looking at it as an open spot, so I could come back to Jasper, and then sort things out.

So I moved back to Jasper, I sold my house in Invermere and bought a house in Jasper. It was nice owning your own house, but I remember Cheryl saying to me “How come they keep costing more every time we sell, we buy houses that are more expensive?” It’s just the nature of the beast … you are living in Jasper. Anyways, I moved back into Jasper and got called into the Chief’s office. It was still Paul Galbraith, but he was working in concert with Brian Wallace, the incoming Chief. They said “We have a project we want you to work on. We’re going to put you in the job at Mile 45. And I went, “Whoa wait a minute here, I just bought a house. I’m not moving to Mile 45”. They said, “Don’t worry about it. We’re parking you in the position because it’s vacant, but we’ve got a project for you to work on.

So I ended up working out of the Admin office in downtown Jasper and I worked on the movement at the time, of the rafting companies that were booted off the Maligne River to protect the Harlequin ducks. It was Parks Canada’s decision that they would find them other places to run their businesses. That was my job.

I was on a project working with the Ecosystem Secretariat, the Warden Service, and the Superintendent, on moving the rafting companies from Maligne down onto the Sunwapta River, doing the environmental assessment, getting put-in spots and take-out spots built with the maintenance guys, and doing consultation with the rafters and the public along with a fellow named Keith Shepherd who was working at the time in Finance and on special projects.

So I moved back and I had a job and I did that. I knew most of the rafters because I’d been the District Warden at Maligne. So I knew most of the guys and they knew they could talk to me. So we got all of that done, and then of course they had to find something else for me to do. So that went on for probably…I was there in August or September of ‘98 and went through that in that winter. Then in that winter I was assigned the closure of the airport in Jasper and that was going to court with the group called COPA, the Canadian Owners Pilots Association.

I took the lead on that working with lawyers that were working on behalf of Parks Canada. They weren’t prosecutors, they were lawyers defending Parks Canada’s decision to close the airport. I worked on that through til the spring of 1999 and we lost in Court, as an aside. The judge found in favour of the pilots. Thus, the airport is relatively open I believe to this day. I’m not sure, but I know every time I go up there, there are planes parked on the runway.

I’ve done a lot of different things, Sue in my time. After that I then competed, and I got the acting job of Ecosystem Secretariat Manager. Ron Hooper, the Superintendent at the time, actually came and asked me if I’d apply on it, and so I applied on it and I got the acting job so I did that starting in the fall of 1999. I was Ecosystem Secretariat Manager until the spring of 2000 when they hired Kevin Van Tighem. I had applied on the job, but I withdrew my application at the last minute because I realized I didn’t want to.be in the planning section. I wanted to be a park warden or something in the Warden Service. As I told Ron Hooper, “I’m green Ron, I wear green”. Then at the same time he said I have an opening in the Chief’s job so I’m going to offer you the Chief’s job as a temporary stay. So, I moved from Ecosystem Secretariat to Acting Chief for two months in Jasper. I moved around a lot and got a lot of different experiences. When I was Chief, that’s when the Moab Lake fire was going on in Jasper. Steve Otway was the Fire Boss, Incident Commander on that, so I got to know Steve pretty good, not knowing that eventually he was going to be the Chief in Jasper. So I did that and then everything sort of calmed down …. I got to go back into just operational work and that would take me into the fall of 2000, and that’s when I applied for the Resource Conservation Manager, or the Chief Park Warden’s job in LLYK. So, I competed for that and I guess I had a better day than the other guys and I got that job in February of 2001.

SH: I’m surprised at how many things you’ve done Ed.

Ed: I know, when I was trying to prepare for this a bit, trying to remember what had gone on, I thought “This is almost conceited. I’m just going to be talking about myself.” I did a lot of different jobs in quite a few different places.

SH: No Ed, that’s part of the game here. It’s all really quite interesting. Do you want to go onto what you did and didn’t like or continue with LLYK?

Rob Walker and Ed Abbott, Remembrance Day Service Invermere, BC.

Ed: I think I should go on with the job in LLYK. I started the job in February or March 2001. I had been there before so I kind of knew the challenges of the field unit, just because I had worked there as it was being formed in the ‘90s. The sheer scope of the field unit was just unbelievable. Until you work in it, I know other parks, I know Ian Syme in Banff who got to be a chief about six or eight months ahead of me off that list that I talked about earlier …. I think he had an appreciation of it, but I don’t know if the folks in Jasper did. We were so spread out in LLYK from an administrative point of view; I had three offices and we straddled the border so I was dealing with departments from the Province of British Columbia, the RCMP in British Columbia, the RCMP in Alberta and departments ….

It’s a very complex field unit and grossly underfunded. We looked at things to try to make ourselves more efficient, but we actually found in many places the management plans actually prevented us from doing things. The management plans had been written for each of the individual parks and there had been commitments in each of those management plans about having a presence, having offices, providing employment, those sorts of things.

So as much as we tried to consolidate and make ourselves a little more efficient, we were actually getting stymied by the very plans that were supposed to help us manage and administer the parks. It was a challenge and of course the first thing that came in that spring, of my first 4 or 5 months of being the Manager of Resource Con was the gun issue or the arming issue. …. and the shutdown of our law enforcement capabilities.

That took our work on a whole new trajectory for about the next four or five years. I found my job … my job was to try and keep everybody focused. Doing something that was good for them but also good for the park because we were not doing law enforcement. I’ll be frank, there was probably about 50% of my staff in the field unit of the Warden staff, that supported arming and then the rest probably just didn’t care. So, it was a long drawn out process and I’m not going to dwell on it but that was one of the biggest things was to keep morale going and keep everybody focused on managing parks. The job was still a good job, and that for me was a big thing…trying to keep staff focused.

Other things came along that took precedence. We were looking at right sizing our organization, after many years of growing and changing to be more science based, and science oriented. We had a lot more specialists working for us in Resource Conservation. We had people like Mike Gibeau, and the fire guys, looking at prescribed fires.

We had moved from being a pseudo-science based organization to quite a science based organization.

Nobody can forget in 2003 what happened with the fires. Probably the largest emergency in Parks of Western Canada. Closing the backcountry down in 2003, the fire in Kootenay, the fire in Banff and then of course the fire in Jasper all going on at the same time. That stretched all of us, to pretty much the end, but as usual, Parks Canada, and this is about the Warden Service, they did their jobs, and it was a memorable 2003.

SH: I remember it well Ed. What a crazy summer.

Ed: You know, our little world was within Parks Canada, but of course at the same time in 2003 they lost 239 homes in Kelowna, where I live. As it turned out I bought my house here in 2007 and my house was on the fringe of the fire. There were houses on this block that burnt down. It goes around and that was a big year in BC for fires. The Barrier fire where they lost the sawmill and everything …. ‘03 was a big year, and stressful but I think everybody was very proud of the way it went. We lost one facility; we lost the Fay Hut. We burned some campground stuff down, but we saved everything else. Jasper, I think lost one or two backcountry cabins but that was a huge fire. Our fire was 18,000 hectares and Jasper’s was 31,000 hectares. Those are big fires.

It’s kind of hard to go back and look at all these questions.

SH: Yes, it’s wild when you look at all the experiences, isn’t it. Interesting lives people led. (Tape 1:17:53). The other thing that was different from our perspective, maybe not yours, but in your field unit, was the whole commuting thing was bizarre in LLYK. People drove a long way to get to their jobs.

Ed: Oh ya. When you really think about the actual formation of LLYK, you have to think that you solved a few problems and probably created a lot more, maybe not for Parks Canada, but maybe more for all of its employees. Most of my career I lived at stations, and you put your hat on and you walked out the door, and you were on duty. Or you had a 15-minute bike ride to get to the office. When we formed that field unit, housing was very inadequate in the Lake Louise area, and quite frankly, it was full. We needed people to live at the lake and we were lucky that we had wardens that wanted to live there. People like Ivan Phillips and Rhonda and Joe Owchar. We needed people to have an emergency response capability without having to drive for fifty minutes. But for the rest of us, it became quite grueling.

Management ended up putting in commuting allowances. I would drive in a carpool. we would leave Canmore in the morning with two or three other people, Mike MacInnis, Jamie Fennel, Bill Hunt, and we would drive 50 to 55 minutes to get to Lake Louise. There were lots of days when I would get there and go on my computer for 20 minutes when I’d look at email, and then I’d hop in my car for work and I’d drive all the way down to Radium Hot Springs, because I had an office down there. I would drive down there because many of my staff were down there; my science staff, the wildlife people, the social science people, my admin assistant was down there. So, I would drive down there for meetings, and then drive back to Lake Louise and sometimes I could take the car home, or sometimes I’d have to drive back to Lake Louise to get my own vehicle and go home. A day like that, we were talking 280 km of commuting. I spent hours in the car. The saving grace was as soon as I dropped into Kootenay Park there was no cell phone coverage, so I didn’t have to talk on the phone while I was driving.

You had an hour and a bit drive of peace and quiet other than maybe the radio once in a while. It was a very challenging field unit and I’m actually quite amazed that it’s still functioning as a field unit after all of these years. I’ve been gone quite a while now and they are still holding onto it. But it was a challenging field unit. Nothing was easy it seemed. We complained about money as a field unit. But even lots of money wouldn’t have helped. It’s a large, complicated field unit. When I left, I had been the longest standing Chief, that they had. They switched Chiefs so many times since the inception of the field unit. Now guys like Rick Kubian have surpassed that one, because they got in and stayed for quite a while.

SH: What did you like about being a Warden? What didn’t you like about being a Warden? (Tape 1:23.31)

Ed: I think the one thing … and I read some of the other interviews, I think the one thing most people liked was the variety of the job. You went to work every day and you never really could be assured of what you might be doing. I think that was the thing I really liked about it. You never got bored, that’s for sure, unless you got stuck on doing some kind of … which I did once, I got stuck updating the conservation plan, which means you just sit at a desk and type. When I had that, we didn’t have a computer so that became onerous. But the good thing about the job was that every day was an adventure, and you were outside. I think that was the thing that I always liked…you had to go outside to do something. And you were working with like-minded people which was really nice. Not everyone thought the same, but you had one strong thing in common. You were all wardens, you’d all been through some of the training exercises, you’d been on the public safety schools, you had slept in the tents, you’d slept in the snow caves, you’d been out in the cabins. That builds a very strong comradery amongst a group. It’s the thing you see with police departments and firemen, and I guess the military to some extent. You work and you play together. That was really what kept it great.

What did I not like about it? Not much. I think the one thing that I didn’t like about it, was I could never understand why different departments like Highways and Trades and the Wardens couldn’t get along better. There always seemed to be a bit of friction, particularly the highway maintenance folks. I know that because I worked on both sides of the fence, I worked in both departments. It was like we weren’t all pulling oars in the same direction sometimes. That was probably the thing I liked the least … the fact that we didn’t all seem to get along as well as we could have. It wasn’t totally dysfunctional, but you could always feel it. You’d go in and get something at the Garage, your vehicle would break down and they’d give you a hard time and you’d go “Why. I didn’t mean to break it, it just did.” So that was a thing.

Paperwork…. there’s always paperwork. If you just got on with it, you got better at it. I did lots of it when I was the court warden, so I guess I got used to doing paperwork and as a Chief there is always paperwork. That’s it.

SH: What are some of the more memorable events of your Warden Service career? (Tape 1:27:40)

Ed: I remember just a few things. It’s amazing how fast you can forget this stuff after you’ve been retired for a while. One small thing I always remember, the “Oh Wow Event.” When I was at Elk Island, as most people know, we would round up the bison, or as many of them as you can, and you would bait them into large enclosures and then we would move them, and we tried to handle them. We had squeezes like you’d use on cattle. Some of them, would be just to get general health; we would take the blood from under the tail. Some of them might have been for sale, and we’d have to get an age structure of each package that was sold to ranchers and that sort of stuff. But I always remember we were doing this one year and there’s always a group of big bison, the bulls, that you never seem to get in. They march to their own tune and quite frankly who is going to argue with them. We managed to get a bunch of these guys into the enclosure, and we were going to try and put them through the squeezes to, like I said, try to get blood samples, just to check on the general health of some of these old big guys. We had one bison, and he did not want to go into the squeeze. …. Absolutely refused to go into the squeeze.

Ed Abbott working with Bison at Elk Island National Park

We were working up above and I think it was probably Chuck Blythe who finally said “Let’s just let this guy go. Let’s kick him out and let him go. He’s just being a pain and we’re not moving any of the other bison in because he is being so stubborn.” I remember we opened up the chute, and we let him out. So he goes into this big long chute, that you could park a truck in …. It’s big enough. He runs in and he hits this huge gate, and this gate is made out of wood. So this is back in the ‘80s and a lot of things were built out of heavy duty planks of wood, the gates, instead of metal. He got down to it and he hits this gate, and he bounced back off of it, and he got mad, so he went up to the gate, and he hooked his horn on this gate, and he lifted the gate off the hinges. We stood up there watching this, and he ran down the laneway in the area, he’s still enclosed, and he’s running with this gate hanging on his horn. He flips his head to one side, and this gate goes up in the air, flips over and lands on the ground. He doesn’t break stride and keeps running, and he hits the wire fence at the end, and he blows right through the wire fence. So he’s back out of the management area but still in the park, so we’re not worried. But we just stood there in awe that this guy ran with this gate hanging on one horn and then flips it over top of himself and then runs through the wire.

We had to bring a hiab truck in to pick up that gate. So it’s a truck flatbed with a bit of a crane on it. That’s how heavy this gate was. We had to bring this truck in, lift it up, and bring it over to rehang it back on the hinges that he had picked up on his horn. The absolute power of these animals. That was the biggest demonstration we’d ever seen. It was just like “Oh my God.” We couldn’t even pick the gate up and he was running with it on one horn. It was just amazing.

Other things …. Some of the schools that we were on. I looked at Gerry Israelson’s interview and he referred to Willi and his tent and how he had a hole cut in the bottom of the tent, so that he didn’t have to get up in the middle of the night to go to the washroom. I remember on my first Eight Pass trip that I went on, I was a newbie so to look after me they put myself, Willi and Dave Carnell in the tent. So we’re in Willi’s tent. I’m not going to say that it was easy. This was a tough thing. It was one of the first really cold trips … It was -35 and the first one that I went on, we weren’t allowed to take stoves. We had to cook on open fires. So we are on the trip and we get to our first night’s camp, and I’m not saying I’m not struggling, because it’s hard work. I’m with a couple of veterans here and the public safety specialist for goodness sake. So, we set up the tent … you pack all the snow down so your tent will have a firm base and I figure okay I’m going to get in there and throw my stuff in. But exactly the same thing …. I get in there and I’m unaware of the hole in the floor. I throw my foamy and my sleeping bag down, and get it all set up and I go in later on, because we are cooking on the fire. So I go back over to the tent, probably a couple of hours later and we are all freezing our butts off. I go into the tent and here’s all my stuff thrown into the corner on the other side of the tent. What the heck is this? My sleeping bag, my foamy, all my stuff is just tossed on the other side of tent. So I don’t say anything, I just go and grab my stuff and of course Carnell has got the other side of the tent. So Willi is on one outside wall and Dave Carnell is on the other outside wall so I’m in the middle with the pole, as Gerry said in his story. And it wasn’t until the end of the trip until somebody told me “No you don’t go on that side of the tent. That’s Willi’s side of the tent, this is Willi’s tent, and he’s got a hole so he can just open up his sleeping bag and have a wee in the middle of the night without getting up. Who knew? I remember that …. that sticks in my mind, how I walked into tent and all my stuff is in a pile after I had it all laid out, nice and neat and thought I was being good, getting all my stuff ready, and trying to impress the boss, and he throws all my stuff across the tent.

If I can prattle on, I remember my first winter in Rogers Pass we got called for an avalanche rescue down at what was called Mount MacKenzie Ski Area, which is now Revelstoke Resort. I remember going down there, and never having been on avalanche rescues before, being trained but not participating, and flying in with a helicopter and seeing the slide that had broken out. Mount MacKenzie had started cat skiing at the upper end and two skiers had gone into a depression and cut a slide out. It was the first time after we recovered them, you could see why you don’t wear pole straps when you’re skiing in avalanche terrain. Both of these people had their straps on, and their hands were buried down below them. Just things like that. We had two of those, two in a row one year and then another one in ‘80/81 and I think by then Gord Peyto had his first avalanche dog. I think we used that.

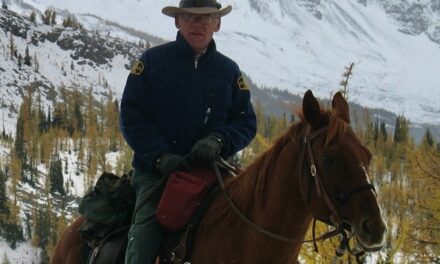

Ed Abbott on Mt. Lyell. Lyell Icefield.

I can remember being caught in an avalanche myself in Rogers Pass, in my truck, driving down the highway during a full closure. We had been shooting for hours, or the Snow Research guys had been shooting for hours. We were spelling each other off, on different parts of the closure. I’d had a chance to go in and have a bite to eat. It was dark, it was snowing, and the road was closed. I was going to go down and let somebody down at the Provincial snowsheds and let them come in and I was going to hold the traffic that was held at the sheds, for their own safety. I’m driving down, and there’s always two philosophies when you’re driving through Rogers Pass. Either you go really slow and watch for stuff that might come down, or you go really fast and hope that you beat it. I chose the latter, and I remember driving down, the road closed, howling wind and snow, and I’ve got all the lights on and everything and all of a sudden I can see what I think is a snow drift across the road, and then I realized no, it’s avalanche debris. I hit my brakes and the truck was flying along at about 45 km/hr and I hit the leading edge of the snow and my truck went up in the air and flew down and dropped into the snow, into the avalanche debris and it killed the engine. It was instantly quiet, other than you can hear the red and blue lights spinning on the roof of your truck. The truck was buried right up to the windows. I had to call out, and at the time it was Fred Schleiss who was running the program. He said, “Stay in your truck, we’ll come down and get you.” They came down, and I rolled down the passenger window on my truck and climbed out the passenger’s side because the slide had come down on the driver’s side. I walked to the back and then they brought the gun down and shot and I think they probably put another 200 or 300 meters of avalanche debris behind my truck. Lots of exciting things that happen in your life, and some of those things stick with you.

I have one more if I may?

SH: Absolutely

Ed: I remember when we worked at Marmot Basin, I was a seasonal, and we actually had a 106 recoilless rifle up there for shooting the high targets in Marmot Basin. We went up and we were shooting, and we shot at one target, and it was a dud; it didn’t go off. So we had to go find it. So you leave the gun aimed where we were shooting so you can kind of find where it hit. I remember Darro and I going up and I think it was John Niddrie who was on the gun watching through the eyepiece. We went up, and it was within the ski area, so we had to close it all off and go find it. So we were walking down this snow slope, we had our ski boots on, walking down this slope. We are saying “Tell us when we are there John,” on the radio. John says “Okay, you’re there.” So Darro and I start digging down and it turns out we’re standing on top of this 106 unexploded ordinance. So, we kind of gingerly step off this thing and we set up. I go up top and put a rope on Darro. We had some explosives with us that we wrapped up and put a long fuse on, and set it down and fired off the explosives that we brought up. He was climbing up and I was pulling him on the rope. We climbed up and get over the top and get away from the explosion we detonated off on the slope. It was one of those things …. Are we on it, are we near it? Ya, you guys should be close to it. We were close to it alright. We were standing on top of it. Those are just some of the things that stick out in your mind when you reflect back.

SH: Not a lot of people can say they’ve had that experience.

Ed: No exactly. Everything works out for the good, so you get to have a beer and you laugh about it, when you recall it.

I’d be remiss if I don’t say something about Pat Sheehan’s passing in November of 1992. He and I were good friends. We’d done quite a bit of scuba diving together, we’d gone out to the Queen Charlotte’s together and gone diving. He was a very good friend and a tremendous loss. And then Mike Wynn. I didn’t know Mike Wynnn very well. I knew of him, but the other folks that were on the trip with him that day, Randy Fingland and Brad Rominuk, I knew those guys. The lasting effects of those sorts of things you don’t forget. Nobody wants tragedies to happen with people that they know.