Over the years, I visited Bill regularly while travelling up and down the Brazeau Valley. He would put on a pot of strong cowboy coffee, roll a smoke and tell stories. He told me about how he used to pack horses with Joe Back in Montana. Joe Back is famous in the outfitter world for his book Horses, Hitches and Rocky Trails which is known as the Packers Bible. Bill had a thick down Eddie Bauer sleeping bag. Bill would often say when asked about his sleeping bag – “Eddie Bauer. Knew the man I did. He would roll over in his grave if he saw what they are selling in his stores these days”. Bill was referring to the fact that Eddie Bauer used to make quality rugged products for use in the wilderness but have now become more of a fashion store.

Bill had a small garden. He grew rhubarb, horse radish and Netted Gem potatoes, as well as a few other root vegetables. Bill had three possessions that he called “Old Betsy”. One was his Lee Enfield .303 rifle which usually hung above his bed, if it was not outside with him. Another Old Betsy was his Honda quad ATV. The third Old Betsy was his chainsaw.

On April 2, 1992, I was invited to come on a helicopter flight to fly to several snow-survey plots in the south end of Jasper National Park. The plots were among those set up by ATCO Electric so they could estimate the amount of spring runoff to hold behind the Brazeau Hydroelectric Dam. This was a great opportunity to see my district from the air in the winter and to see if there was any human activity along our boundary. As we were flying up the Brazeau River near Dowling Ford, I spotted a cow elk standing in the middle of the river. I asked the pilot if we could have a closer look since elk usually do that to avoid predators. Sure enough, as we got closer, I could see eight wolves on one riverbank and five more on the other. All were bedded down, curled up with their noses tucked into their tails. They knew it was just a matter of time before the elk had to come out of the river and they were waiting with both sides covered.

We left them to work things out and continued further up the Brazeau River. As we flew over Trapper Bill’s cabin, we saw Bill standing on the seismic line waving his arms franticly trying to get our attention. I could see carcasses of a cow and a calf moose on the gravel bar in the park just opposite Bill’s cabin. We decided we had better set down and see if Bill was alright.

When I got out of the helicopter Bill recognized me and said “Mike, am I ever glad to see you. You won’t believe what happened. There was a sick cow moose over there. I had to shoot it to put it out of its misery. When I cut it open, I looked at the lungs and it had radiation disease from Chernobyl.” Bill was referring to the radiation leak that had occurred at a nuclear power plant in the Ukraine several years earlier. He then pointed to a stand of dead trees further downstream and said they must have been killed by radiation as well. Bill showed me the moose lungs and I could see there were some obvious large yellow cysts on the lungs. I took a photograph of the lungs to show to a wildlife disease expert when I returned to the warden office. I spoke with Bill for a while. It had been five months since he had last seen another human being. He said besides the radiation in the valley, he was OK and did not need anything. He added that Rod Estay from Highland Helicopters in Edson would be flying in supplies of fuel, food and medicine next month and he would be fine until then. So, we continued on with the snow-survey flight. I later showed the photo of the moose lungs to a disease expert from Alberta Fish and Wildlife who said the cysts were from tapeworms and that it was not uncommon to find them on ungulates.

Later that summer, Bill offered me a jar of canned moose meat. I politely declined the offer.

In late October 1992, I was on a fall boundary patrol with Joan, my wife-to-be, and horses Julie, Indigo (aka Frank), Zambia and Traveller. While staying at Isaac Creek cabin, I rode over to Bill’s place to see how he was doing. I could see smoke coming out of the chimney and I called out to let Bill know that it was me. He called back inviting me to come in. Bill offered me some coffee but he looked a little concerned about something.

He said “Mike! You won’t believe it! When I have a bowel movement [paraphrase], my guts come out. I have to push them back in with a sterilized pad. Do you want to see?” I said “No, I’ll take your word for it Bill”.

It sounded like he had a prolapsed colon. I told Bill that he needed to go out and have a doctor look at it. He did not agree that day, but the next day when I came back to check on him, he asked me to order a helicopter from Highland to pick him up. He gave me a supply order of fuel and a few other items for the helicopter to bring in when it came, so that it did not come in empty. That night I passed the request on to our dispatch via the single side band radio. The next morning on radio call, the dispatcher said that Highland would come in at 9 a.m. the following morning to pick up Bill.

Well, the next morning came with a snowstorm blowing in from the east. The wind picked up and snow was coming down on a steep angle. I headed over to Bill’s place to help with the evacuation. When I arrived at Bill’s cabin, there was no smoke coming out of the chimney which was not a good sign. And even though I had called to Bill from the seismic line where I tied up my horse, I heard no response. I went to the door of the cabin and standing to the side, I called to Bill again. This time I heard a few moans and groans. I called again, “Bill, It’s Mike. Can I come in?”

Finally, Bill said yes, so I opened the door. There was Bill in bed under his Eddie Bauer sleeping bag. I could now hear the helicopter in the distance making its way up valley in the snowstorm. I said “Bill, you better get up, the helicopter is going to be here soon.” He said, “I ain’t going anywhere.” He told me to get out and leave him alone or “it would be war”. I said, “Rod Estay is coming a snowstorm and he won’t be happy if you don’t fly out”.

Bill replied, “Me and Betsy ain’t going anywhere.” It was then I noticed that Betsy, his rifle, was not on the wall above his bed and it was nowhere else to be seen. My guess was that it was under the Eddie Bauer sleeping bag. I said, “Ok fine”, as I heard the helicopter landing down by the river.

I went to the helicopter and shook hands with the pilot and the engineer who turned out to be Rod Estay. I told them that Bill said he was not going anywhere and that his rifle was not in its usual place.

Rod said, “I have known Bill for a long time. I’ll go and get him.” I helped the pilot unload the fuel Bill had ordered and just as we finished Rod returned in a rush and said, “Bill’s not going anywhere.” The full brunt of the storm front had not arrived yet and as Rod and the pilot were in a hurry to get out of there, they hopped in the helicopter and took off. I decided to ride up valley to Job Creek to see if any hunters had come in from the province in the last few days. When I got to the Job Creek trail, there was no new sign of any horses in the area, so I turned around and headed back down valley towards Bill’s place. The storm front had passed and the wind had died down and it was snowing lightly.

As I rode towards Bill’s cabin, I could see that there was smoke coming out of the chimney. I yelled to Bill that it was me and received a reply to come in. When I opened the door Bill was sitting on the bed and Betsy was hanging on the wall. Bill seemed much more coherent than a few hours earlier. I said, “Bill, Rod’s not going to be happy.” Bill said in a surprised way, “No! Why?!” I said, “because he came in a snowstorm to pick you up and you didn’t go.”

Bill’s reply, “No! He didn’t? He was here?!” “Yes.” I said “And you didn’t go out.”

I was not sure if Bill was pretending not to remember or if he really did not know that the helicopter had come in to pick him up. He claimed that he thought he had been dreaming. I knew from other occasions that sometimes when Bill had hurt his back, he would take a mixture of his medications and would pass out for a day or two and when he came around, he would be feeling better. I wondered if he might have overmedicated earlier that morning. So, I left him that day and the next day Joan and I moved to Southesk cabin.

A couple of days later we returned to Isaac Creek cabin and I rode over to see how Bill was doing. It was his 72nd birthday. He was in about the same condition as when I had left a few days ago. However, he said that he needed to go get some medical help. He asked if I could ask Highland Helicopters to come in again to pick him up. I told him that I would order the helicopter, however, Joan and I were heading to Brazeau the next day so we would not be there to help. He would have to go out this time. He told me he was afraid to die or be stuck in a hospital and that he wanted to die in the bush, however, he would go out this time.

I arranged for the helicopter on radio call that night. The next day Joan and I headed up valley to Brazeau cabin. It was now late October and after a few days at Brazeau we headed out of the district for the last time that season.

Now, the rest of the story. Bill did indeed fly out when the helicopter arrived. By the next backcountry season, Bill was back in his cabin along the Brazeau River. He stayed there for the next couple of years before moving to a cabin on his trapline which was 8 Km. up the Blackstone Gap Road from Highway 11. This cabin was easily accessible by quad or snowmobile so it was a safer location for Bill.

I kept track of Bill’s health and whereabouts through John McVey. In the late 1990s, McVey told me that Bill had moved to a single men’s rooming hotel on Vancouver’s downtown eastside just off Hastings and Main streets. While on vacation to the Sunshine coast, I visited Bill to see how he was doing. He said he was doing OK but missed the bush. He was very happy to see someone from the Brazeau Valley because it reminded him of a better place and better times. He said he just about went into orbit when the guy on the front desk of the hotel told him that I was downstairs looking for him. He told me he didn’t like being around all of these strange people and he didn’t get along well with some of the other residents in the rooming hotel. A few years later, McVey told me that Bill had moved into a mobile home up a rural road, 5 Km. outside Powell River B.C. at the north end of the Sunshine Coast. He said that Bill was not getting along well with some neighbours and that the RCMP had taken away his firearms. My family and I were in that area on another summer vacation in 2001 and while in a coffee shop in Powell River an RCMP sergeant came in for coffee. I approached him and explained who I was and asked if he knew a Bill McDiarmid or Trapper Bill McDiarmid who lived somewhere just outside of town and was not getting along well with his neighbours. The sergeant said that he did not know of anyone by that name. A few years later I contacted John McVey to get an update on Trapper Bill and learned that he had passed away in 2007. He is buried in the Powell River Cemetery.

Trapper Bill. Knew the man I did. He would roll over in his grave if he saw how the world has changed.

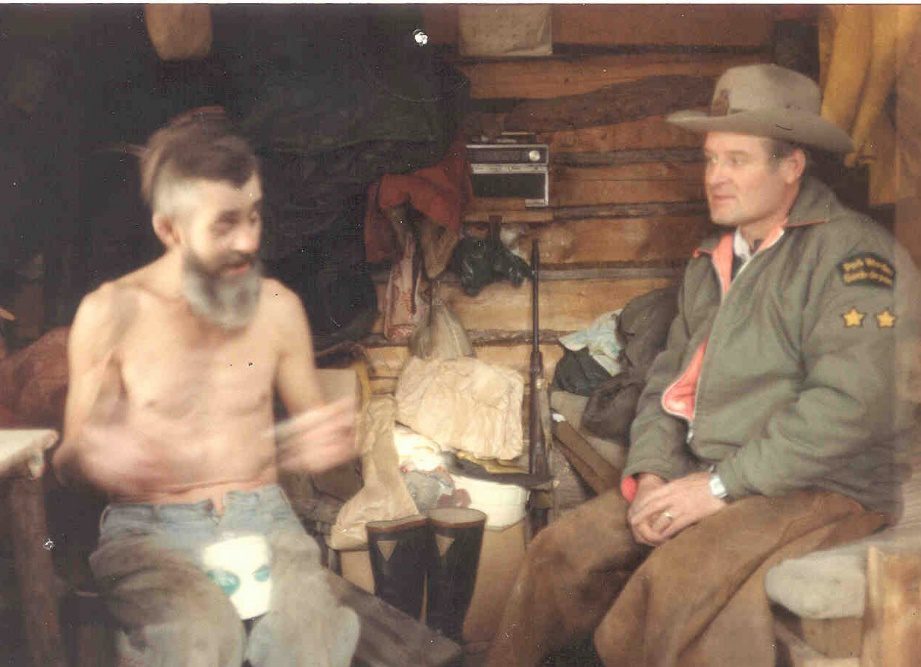

Trapper Bill rolling a smoke with Chief Park Warden Don Dumpleton. Note Old Betsy in the background.

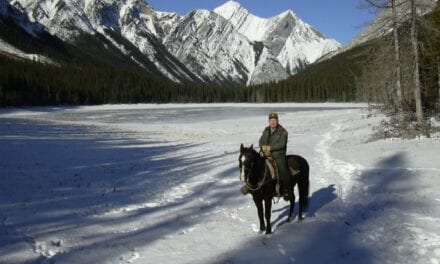

Rick Kubian, Joan Avis and Trapper Bill – 1993

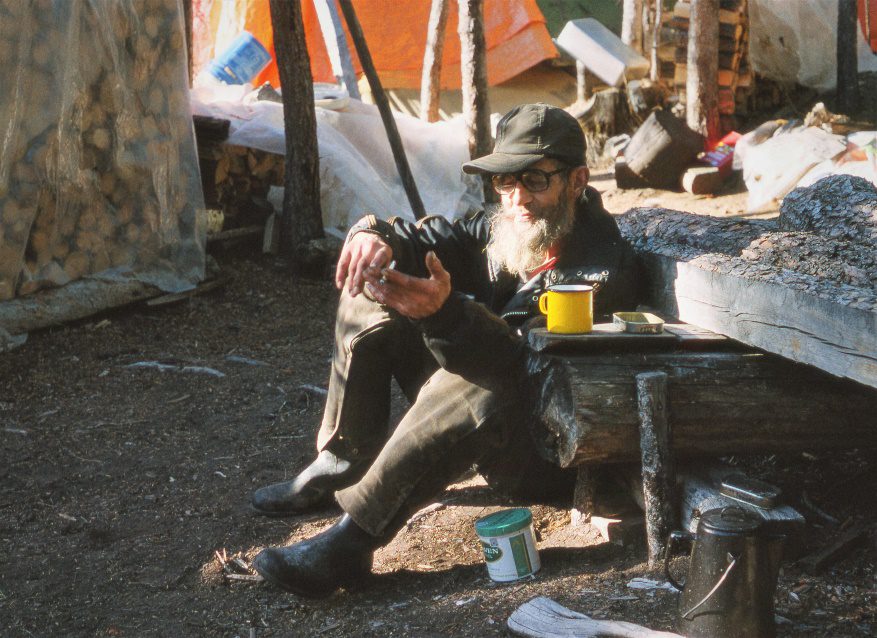

Bill telling stories on a sunny late autumn afternoon

MH: How did the Warden Service change over the years?

MD: I started in the mid to late 80s, so in my time, specialization was one of the big changes over the years. I started off in Operations, we were involved in everything. You would fight fires, do rescues, manage problem wildlife, do law enforcement, a little bit of everything, and then over the years, it really came down to you could still carry a stretcher for public safety, but no more heli slinging. The fire guys were the first ones on the fires and if they needed someone to grub a fire line or something, then you might come in and help with that. And I guess the safety standards were part of the reasons for some of the specializations too. When I first started, we operated chainsaws without helmets or even hearing protection, no chainsaw pants or other safety equipment. That sort of thing was just normal. And solo horse trips where you would be out sometimes 15 days by yourself. Now I think you pretty well have to travel with someone else.

The communications have improved and changed. We went from single sideband radios, to satellite phones or InReach and Spot type devices that you carry with you. We used to be able to travel with our spouse or friends in the backcountry on horseback and/or hiking. Now the standards for being able to ride a horse are fairly stringent and you have to go with a mentor or something like that. One of the other really big changes too are computers and the things that they brought, some good and some not. The number of emails that you get nowadays can be overwhelming and you can spend almost your whole shift just about doing emails. In the old days, if somebody had sent in a comment or a letter to the park, it would take two, three days to arrive, you’d take a couple of days to write a response, and then mail it back out. If they wanted to comment again, they would turn around and write again and the whole thing would take a week or two. And now you send an email, 10 minutes later, you get an email back. So you send another email and you get another email back. So much time spent inside on computers doing business with ourselves instead of being outside in the park. That is one of the biggest changes.

And then obviously, Law Enforcement was one of the biggest changes. Only actual wardens can do Law Enforcement, and they really don’t do anything else. They’re not overly involved in any of the other functions other than maybe traffic control at a rescue or at a fire or something like that. There used to be approximately 40 wardens in Jasper that could do law enforcement. Today there are a maximum of six warden and sometimes as low as three wardens that can do law enforcement employed in the park. So that’s one of the huge changes.

Also during my time there was the increase of women in the warden service. It was not the very beginning of women in the Warden Service, but it was a time where there were a lot more women coming in. Kathy Calvert, Betty Beswick and Jean Stoner were some of the very first ones but then, folks like Trish Tremblay, Jane Emson, Heather Davies, Monika Schaffer, Patty Walker, Brenda Sheppard, all these folks started coming along. That was one of the bigger changes and better changes in the Warden Service during my time.

MH: What about the Warden Service was important to you?

MD: I think the protection part was pretty big with me, I liked to protect the park and the ecosystem. It was always satisfying when you had a successful rescue after somebody got themselves into trouble. And then later on, working in the Cultural Resources section. I enjoyed working with indigenous people. I found it pretty rewarding. As well as protecting cultural resources. Almost nobody, even in the Warden Service, really cared much about cultural resources, whether it be archaeological sites, or historic buildings, the National Historic Sites that are in the Park, that sort of thing.