“Did you think Parks was the way to go, or did you ever consider just doing the guiding?”

(1:11:10) The answer to that is the summer job was fantastic. Gradually, I mean it was obvious, there was this functioning (entity) there which was the warden service. In other words, there were people (working fulltime) and I learned about it. Meanwhile, what I was doing also was I was beginning to form the idea that this was maybe going somewhere, in terms of the safety side of it. I mean we were all there, it was in an era when there was an emergency the wardens would respond with Mounties…depending on what the problem was. If there was a forest fire we all became fire fighters. If there was an emergency in the mountains we all became involved in whatever capacity that we were able to try and resolve it. The Mounties weren’t going to climb anything back in those days and most of the wardens were skiers, not necessarily great skiers. And I began to realize that this avalanche business was something that you had to pay attention to and learn.

(1:13:09) Through that period where I was working as a summer warden, I would keep getting these offers and having the senior guy from Calgary coming out and putting his arm on my shoulder and saying, “Tim now, you’ve got make your mind up someday…” I kept dodging the bullet you know. But finally (I accepted the offer). Like I keep saying over and over it happens coincident with me getting the guide’s license…they kept offering me jobs, but it meant that I would have to go somewhere else, like Jasper or Glacier. I just had a sense that these places in terms of emergencies weren’t the busiest. So what happened was…they finally offered me a job in Banff. And not only that, the job was offered to me at the same time that the Chief Warden (Andy Anderson) and Rick Kunelius and one or two others had begun to talk about the idea that they could improve the service in the public safety area. The park had Peter Fuhrmann, the Alpine Specialist, and he was the guy who was really one stop shopping for the big difficult stuff. He was there, he was a guide, he knew where to go to get the helicopter and this and that…But Andy Anderson and some of the wardens had started to cook up the idea of, “Why don’t we have a standing group…a rescue team.” Andy was always into cooking up new ideas! He took that and went, “Let’s try it.” One of the people that was sitting at the table was Rick Kunelius. I knew Rick, I had actually helped Rick get a summer job when he was working the night desk at the hotel at Wapta Lodge…I suggested, “You could be like me, you could get a job in the park.” He said, “I am up for it.” So I sent him in, and lo and behold he got a job. Then he turned around when they were talking about the rescue team and said, “Well, I know this Tim. He is really into his climbing and he might be a good fit for this.” And they offered me the job. Once again it took me less than a nano second to make up my mind. For the first time in my life I took a job that was more or less a real job…in the sense that it was a fulltime job. You were committing…What I could see was this image of this kind of rescue team that I knew existed in Europe and they were about to do something like that here. I jumped at the opportunity…

“And that was the beginning.”

It wasn’t really the beginning, it was a continuation. The wardens had done it for years and years, the alpine specialists had covered the bases. The real beginning if you want one has nothing to do with me, it was Walter Perren. Walter for obvious reasons should be credited because he actually came with real honest to gosh mountain rescue training. I can tell that because when I went to work in Banff and started prowling around down in the storeroom in the basement, here were boxes with bits of equipment that I knew were some kind of rescue equipment. I didn’t know how to use them and then I will tell you something, as we sit here if I took a few minutes I could put my finger on the book, the handbook of mountain rescue from Europe…this was the technology of mountain rescue circa 1928. We had stuff like this and still do, in the basement in the storeroom. (pointing to an illustratin in the book). This is stuff from Europe and it is all hand operated, no reference to flying…I met through Peter Fuhrmann, the guy who wrote this book, Waso Maroner…I met him in the rescue room in Banff when he came over to visit.

(1:21:11) One of the things that changed when I took the “real” job was I was now fulltime in winter too. Because we were the de facto, newfangled rescue team, well it turned out that the winter portion of this was us being avalanche specialists and that was when I met you know who, your dad, Keith Everts.

Keith Everts, Lance Cooper & Rick Kunelius

Just to clarify that first summer of the rescue team there was four people. I don’t want to put me first, but there was me, Lance Cooper, Rick Kunelius and Keith Everts. So that very first summer…when it was announced to us that we were going to try out this new thing and in the back of my mind, I am going, “YES! It is happening.” The first thing we did was go out and start stretching our legs and arms and getting fit. We didn’t go to a gym, we went up the trail and the next thing we were up Mount Edith…because I had a guide’s license, I was the leader for that part of the team. We’re going up, climbing and then I can remember that on the very first day and we were up on this little peak and all of a sudden on the radio we get the call, somebody has tripped and mangled themselves somewhere up on the backside of Mount Rundle, so it meant coming in, not slinging necessarily, (but it was a rescue).

(1:23:55) By the way the first slinging that was done in the parks that I know of was (started from Peter Fuhrmann). Everybody knows Peter Fuhrmann had brought this idea over from Switzerland and he got some paperwork to allow us to do something that was virtually illegal to do with a helicopter and that is slinging live loads…people who were harnessed outside the helicopter. That very first summer that I was fighting fires the big helicopters would all come. Then one day more or less towards the latter part of this huge forest fire, a lighter helicopter came in and it was Peter (wanting to) try out slinging guys…We were put into a special harness that he had bought and brought over. This was in the early 1970s. The first time I slung was outside Field, in fact it was down the highway where the native fire crews had set up a big camp west of the compound…We landed the helicopter there and put the weight on and put the rope on and decided that we would do some practice work. Like they needed something carried up to the fire and dropped in a smaller field. There were people standing on the ground looking going, “Whoa, what are they doing?” And we were up there going, “Finally!”

(1:27:03) The other funny thing was that at this camp, this native (fire crew camp) we got picked up… and our mission was that we had to tell them that it was time to go over to the other camp for dinner! He landed me beside the camp fire and the sparks were flying everywhere! I’m going “Oh geez…” I wave this guy to come over, they…were holding down their tents that were threatening to blow away. Oh it was funny! This guy came over and over the noise of the helicopter he had to get his head right next to my mouth and I said, “Tell them it is time for dinner.” We were just kids playing, you know, but that was the start of the real (helicopter use). I mean they had used helicopters a few times, and a couple of times in extremely tricky situations.

(1:21:28:36) There was a (rescue) that had been done in one of the big gullies that was up at Moraine Lake. Billy Vroom was slung into (it) and left there. He organized getting the injured person (ready) so that Jim Davies came back and picked him up and got him out of there. This was like flying a helicopter into an enclosed compartment like in parts of the Grand Canyon or something like that. They were doing great stuff and we just did more of it…

(1:29:47) Things settled down then. The public safety team idea was working and the winter thing we were learning because we got the job of also doing the avalanche control for the ski hills and the roads in the park. We had the real things happening. It wasn’t long before we had avalanche recoveries. Also the warden service had been successful in persuading the department to train dog masters and that is almost 30 years old now and they are still doing it. I stayed in the (public safety) program that was the way we used to talk for the rest of my career. I wasn’t a big boss type and so we had a lot of teamwork going, especially in Banff and we worked to improve the stuff we did. Not just flying and climbing and skiing…but we were also looking after this new area of visitor safety and risk management. We were just sort of an obvious place to put a file that was a little more organized, when Parks had some sort of a disaster or situation. We weren’t just winging it. We wrote plans about the various safety aspects. We came up with the ideas of fences and railings in the appropriate places for good reason, stuff like that…we discovered that the park had a functional responsibility for coming up with some sort of reaction to large scale emergencies. We picked that up and tried to teach ourselves and tried to learn how to write a decent plan to speed up the reactions and so on. When somebody went over the waterfall, we were there. If there were fatalities we had to deal with the Mounties and all that sort of stuff. The Mounties, a lot of them didn’t know (how to deal with mountain related fatalities) and there wasn’t anywhere else in the country where there was some kind of uniformed agency like us. We sort of had turf wars at the beginning, like they were thinking that because there was a fatality involved they had a responsibility to take over, and in situations where the body wasn’t even recovered yet like…they wanted to organize the transport of the fatality after an avalanche accident where you go, “Excuse me, but it is 4:00 in the morning and it is -15 and we are not going to sit here (so you can) play the official guy who has to touch the dead person and pronounce them dead…” That was just an aside, but there was lots of stuff to do the job.

“Everyone I’ve spoken to has said it was a world class organization.”

(1:34:49) You know it may have been, but it was always little, that was the one thing. We kind of pitched over the length of our own arms, but I know what you are saying about world class. Peter Fuhrmann gets a lot of credit for us getting hooked up with the European association of mountain rescue called, The International Commission of Alpine Rescue…Canada was the first non-European country to belong to that. Partly because of him, but partly because of what we did. We could hold our heads up in the meetings that were international. These meetings still happen once a year and you get representation from (places like) Georgia and they may even send Russians now, but (countries like) France, Italy, you name it, most of the major alpine countries and the States now belong too. We were 25 years ahead of the States…We went to meetings with them and showed them what we did. They couldn’t do it with the air regulations as they stood then in the U.S. You did not hang people underneath helicopters. With Fuhrmann’s efforts, he managed to persuade the Department of Transport or whatever it was called at the time that this was something that was such a valuable thing to do that they had to make a special exemption for us to be able to do it. It was genius. It was one of the real reasons that we were as good as we were.

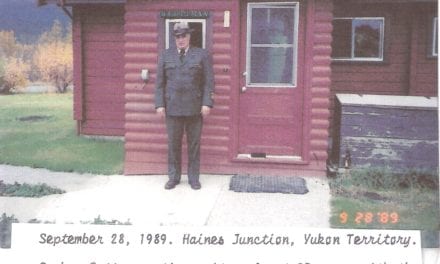

EXIF_HDL_ID_1

Tim Auger, John Nyliund and Gaby Fortin, 1985 Centennial Climb.

1985 Centennial Climb expedition.

(1:37:42) The early years, from the 1960s to the mid 1970s, it (helicopter rescue) was so new that…we weren’t going to buy a helicopter and train a warden to fly it. That never crossed anybody’s mind, and it didn’t make sense. So what we did was we rented helicopters in effect…when it was really in its infancy, it looked so good and so valuable that the government actually got their money out. They got their wallets out and we hired Jim Davies on a fairly permanent basis. Now he never worked for the park, but basically that is all he did. The hanger was built for him in the warden compound. After a while this contravened contracting rules, business rules in Canada for aircraft, for helicopter usage…What really triggered a new change was when people started to say “Hey, who’s that guy in Banff?” Meaning Jim Davies. “How can he sit there and do all this work? We are supposed to be able to bid on work.” That is the way it works, right? When that came up, we had people in the midlevel of bureaucracy in the Calgary office actually stand up to support us, that we needed this special, what was the term? Sole sourcing the contract to Jim Davies or the company that Jim Davies was working for. It was allowed, but fairly shortly after that somebody got their lawyers and it was raised in the House of Commons that this was happening out in Alberta…All of a sudden things turned around and the Transport people were coming out and investigating how we were using the helicopter and so on…one of the offshoots of this was we persuaded our senior management that this was really so important that we had to find a way to authenticate it and get it permitted officially and get it recognized. It was being mentioned in Ottawa and it was almost out of our reach where we could do anything and somebody up there with a bigger tie on was going to be able to say “Yes or No.” And that is what happened (They said the work must be contracted out). We came back and proposed that, “If there is no way that we can avoid contracting out this work then what we need to do is we needed to establish standards for the pilots.” We didn’t need to tell them how to fly the helicopter, but we needed to make sure that…(they) were already mountain trained pilots. So we developed our own pilot test and we went into the pilot training business. Ottawa sent out guys to look at (what we were doing), and they thought that we were crazy. What we did was we arranged visits with these experts who were helicopter pilots themselves who had been hired by the government of Canada to manage the helicopter aspect of air regulations. We showed them what we had to do and what we could do. Like I say, these guys were pilots themselves and they went “Whoa, I get it.” And they went back and they said, “You know they are doing the right thing.”

(1:44:21) We put this guy from Ottawa in the back seat while we did it (pilot testing)…and the way that test goes for the most part is you sit with the clipboard and there is a pilot and (another) pilot in the seat beside him and this was somebody who could take over the controls if things got out of hand…What we did was say to the pilot, “Let’s say this is what’s happening…what would you do in this situation?” Then we showed him what kind of situations (we had) and we threw some real doozers at him. This guy (from Ottawa) got out and he had to smoke a cigarette right away because he had never seen anything like it. Our pilots are some of the best in the world, they really are and they work so closely with us. We don’t pretend to want to fly the helicopter, (but) we know what the helicopter can do. So with everything that we’re doing (we work together). “I am on the ground in a very tight situation, but you can (reach us). I will be here. I will give you the wind direction etc…” It has worked really well.

(1:46:05) We’ve covered a lot of ground actually. I was trying to think about what I would say today, and about six months ago I sat and made a list of possible little stories. In fact it was me saying, “How many times did you break your this…or do that? I made a list of dangerous stuff (I’ve done)…I’ve knocked my teeth out at Sunshine and I fell off of Logan. Then there is…Whiskey Creek, the bear thing…

‘Is there anything about the warden service as you knew it that you would want future generations to know?”

(1:57:37) It is difficult to answer. Like what made it so unique?” What it amounts to is I lived through an era where teamwork was inherent and the use of multi-skills was just a really powerful tool. In other words, we had people that were experts in fisheries, but they were just as good if you got stuck and needed someone to run a fire pump, or if we needed more manpower to participate in a missing person incident where you have to cover the terrain (all wardens would help)…It could have been scaled down (referring to the 2009 changes in the warden service. but they’ve basically tried to blow the guts out of it. (Following the 2009 National Park Warden Centennial Celebrations, the warden service was reduced from 450 wardens to 100 law enforcers across Canada.). I mean it’s bad enough that anybody who has anything to do with science in relation to the national park has been laid off or fired, it’s like, “Oh, we don’t need that.” You go, “It’s nuts.” You’ve heard it, so I won’t waste any more time on it…

(1:59:33) The answer is “Yes!” (to the question, “Do you have any lasting memories as a warden?”)

The following day I met Tim and he said with a huge smile that wanted to add the following… “I forgot to say yesterday, “It was the greatest job in the world for me!”

Tim Auger passed away on August 10th, 2018 at the age of 72. His spirit lives on with the national park warden service and the mountaineering community.

Christine Crilley-Everts’ father was a park warden who was the Assistant Chief Park Warden in charge of the backcountry for Banff, Lake Louise, Kootenay and Yoho national parks. Christine has personal knowledgeable of the Warden Service’s value, history and tradition. Christine earned a degree in history and anthropology from Simon Fraser University. She completed four cooperative education work terms in Banff National Park under the direction of the Cultural Resource Manager Don Mickle. Each work term involved the completion of an oral history project focusing on different themes related to the history of Banff, Yoho and Kootenay National Parks. Christine also completed an oral history project for the Canadian Avalanche Association on the history of the Canadian avalanche industry.