Park Warden Service Alumni Society of Alberta

Oral History Project Phase 13 – 2023

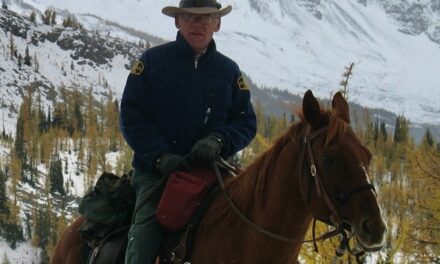

Zoom Interview with Duane West

May 23, 2023– 11:00 am MST

Lasqueti Island and Invermere, BC

Interviewed by Susan Hairsine

SH: What was the place and date of your birth?

Duane: I was born in High River Alberta in 1952. My dad told me that when they took me back in the Jeep to the ranch it was so mild they had to keep the window down so I wouldn’t overheat.

SH: Where did you grow up? (End Tape Part one 01:30) We switched to Zoom as the phone connection wasn’t working.

Duane: My parents were working on the Bar U before I was born which is now a national historic site. I use that as my early connection to Parks Canada. I was joking with Dave Neufeld, Yukon Parks Canada historian, that I was conceived on the Bar U. He asked me what year, and I said “1951”. He said “Oh, the cut off for commemorative integrity is 1950. If you’d been born a year earlier, you’d be a level one cultural resource”.

I was raised on a number of ranches up and down the foothills between Cochrane and Waterton Lakes Park, and home schooled with correspondence for the first four years and then my parents bought a place in the Creston valley. We moved to Creston and were there three years. So going from home schooling, and one thing I’ll mention with the Creston experience, was I fell in love with that interior forest represented in British Columbia so strongly … cedars, big trees … but I had an environmentalist, quite an activist, school teacher. It was the seventh grade and she really opened my eyes to nature. Locally they were debating diking the last of the wetlands in the Creston valley, proposing to make more farmland. So, she and her husband took all of us kids on an field trip, out onto the dikes with spotting scopes and binoculars, and showed us the birdlife and the beauty of the marshes.

SH: Wow

Duane: Yes, it was a profound experience. We lived on the far side of the valley in west Creston and she drove us on the back road, and pointed out eagles in the trees and stuff. It was in my own backyard and I’d never had the eyes to see these things. She was from the Crowsnest Pass and one of the places she talked about so eloquently was the magic of the Flathead Valley west of Waterton Lakes. I never forgot that. Picking huckleberries in the Flathead described by her was like a religious experience. So anyway, that was a big influence on me, an early influence, and from there we went back. I just thought about this the other day. On one of the ranches we were on I created a national park on the hillside above the house, because there was a nice stand of trees, and a gully and rock bluffs, and it was above the creek, so I declared it my national park, and would go and hang out there. It was my park.

The ranches we lived on usually lined up against the forest reserve. One of the few outsiders that would come through would be the forest ranger or the game warden and I liked the idea that these guys were looking out for the wildlife and the forest. I wanted to do that and so then I thought at first of Forestry, and I knew about the Hinton Forestry School. Then at the last minute, the NAIT calendar in the year I was going to apply said if you are more interested in conservation, take a look at biological sciences. So, I changed my application from forestry to biological science. It was a tremendous coincidence that the class I went into in 1970, Bob Wood from Glacier National Park and Ray Frey from Jasper were being sent to NAIT for academic upgrading. Also in my class, Perry Jacobson was there as a student.

NAIT Biological Sciences on a field trip in Jasper National Park. Back Left – Norm Young, Jasper Park Warden. Front: Ray Frey, Perry Jacobson, Duane West and fellow classmates in the Resource Management group.

I took every opportunity to pursue interests in park related stuff. We had field trips to Sunshine Meadows and the Banff Centre, and one to Jasper in winter and we stayed at the Palisades. I doggedly pursued my interest in working for Parks. So, when it came time to graduate, I know they put in a good word for me. Both Perry and I were hired seasonally in 1972.

SH: So that leads us to how did you become involved in the Warden Service? Which national park did you start working in?

Duane: I went to Prince Albert in central Saskatchewan, and again that was interesting because of course as an Albertan, my total Parks focus had always been on … even though I was aware of the system and very interested in the system as it was in those days, I thought I would go to work in a mountain park. I just assumed that. So, Prince Albert, there was a part of me that was quite excited about the idea of the north woods and canoeing, loons, and I had read a couple of Grey Owl’s books.

SH: What different parks did you work in? How did they compare? Do you have a favorite? This is where you rattle off about your career.

Duane: So, I was in Prince Albert for four and a half years, 1972 to 1976, and while I was there, I was quite involved in a backcountry district as a seasonal first on the west side, which is in the area where the grasslands are along the Sturgeon River, where the buffalo herd came to be. They just showed up my first or second year there, but they had come down from the north. They’d been released and just came and found the park and moved in and stayed. It was an accident, they’d been released in the Waterhen, a First Nations community well north of the park, but they shifted down and found the park … I think they were looking for Elk Island and established themselves in the Sturgeon River Valley. It’s a beautiful relic fescue grassland and they hung out there. It was an interesting area. The first year I didn’t have to deal with townsite issues or campground issues, I just kind of had a job putting …. there was a road at the west boundary and we had gun sealing stations. I think there were five gun sealing stations between the destination lake and where you entered the park, because the road wandered in and out of the park. So, we had to go and put lead, and cut sections of string to seal guns into these boxes on posts, when you entered and left the park. So, the fishermen came and took all the lead for sinkers, so the boxes had to be filled quite frequently.

Prince Albert National Park 1973 on Ajawaan Lake. Grey Owl’s cabin background.

Then I got seconded to the biophysical inventory. That was being done by soil scientists and vegetation specialists from the University of Saskatchewan. Francois Millette and myself and one year Doug Burles, we were seconded to the biophysical so the wardens would learn how the data was collected and hopefully how to use it. But my botany strengths were such that they didn’t want to give me up at the end of the first year, so I did three field seasons with them. We trekked across Prince Albert on map and compass transects and backpacked all summer, especially the last one, when we did the north part where there were no roads. You would camp with your partner, or you would be dropped off with your partner and then you would work parallel kind of. The routes were laid out in the features they wanted sampled, so we would be on map and compass, and sometimes they’d put you together for lunch to check on each other, because you’d be out for half a day on your own, or sometimes you only met up at night to camp together. You’d continue on the next day, freeze dried food, backpacking, and doing these vegetation and soil surveys …. Digging soil pits and writing in your little notebook. So anyway, at the end of the day one guy got treed by a bear, things like this. You met moose and bear and there were endless mosquito swamps which were horrendous. When I flew over Prince Albert, I could point out to my coworkers who were doing game surveys, that I camped on that lake, I camped on that meadow. I walked the whole park, back and forth multiple times.

SH: Wow, so Duane were you working seasonally then or was that a full-time position.

Duane: I was seasonal but extended every winter.

SH: What were your winter duties?

Duane: We would do surveys and then often we were snowmobiling the park boundary and there was some maintenance on cabins. But a lot of it was snowmobile patrol on the boundary. Prince Albert had a straight-line boundary and there was a lot of hunting activity. The boundary became a pathway for hunters, the boundary wasn’t cut in the park so in its own right it was an access vehicle, so there was a lot of hunting pressure. We spent a lot of time patrolling that. Then typically there was lab projects and stuff too. We were kept busy.

SH: So, what was your next park after Prince Albert?

Duane: From Prince Albert I went to Wood Buffalo in December 1976. Wood Buffalo … I was three years there. There was such a difference from Prince Albert where you had routine duties, and you were sort of told every day what to do by the way the place was managed. Wardens had all been centralized. There was a lot of sorting out how that was going to work, so we were told every day what to do.

All of a sudden you get to Wood Buffalo, and you’ve got responsibilities. It’s this huge park, very small staff; aircraft chartering, studies, surveys, working with partner agencies. It was a very different situation as well as management style. Al Sturko was a totally different boss. It was probably my first experience with a boss with vision. He gave responsibility and he trusted people to go with it. All of a sudden, one year I was assigned to hire and run the Conservation Core program. Then I got seconded on to a major wolf bison study that Lou Carbin was heading up with a PhD student, and you had significant responsibilities. It was a very different experience. The scope of the park was immense, the scope of responsibilities, the challenge of administering the hunting and trapping, the liaison with community groups, and the hunters and trappers themselves. It was a very different world. There was big scope stuff happening too. The whooping crane egg collection. I just came in at the end when they were still rounding up bison and inoculating them.

Wood Buffalo circa 1978. L-R Robert Loranger, Charlie Ristau, Lorie Collingwood, Ray Whaley, Dan Couchie,

Paul Galbraith, Clint Toews, Grant Hogg, Duane West and Al Sturko.

Before wildlife management and tranquilizing bears, you know with problem bears, just taking them down the road and letting them go, or shooting them, was now trying to round up hundreds of buffalo on this big plain, and head them towards fixed corrals. It was a very different scale and scope so I really had my eyes opened, and got used to a lot of responsibility and loved it.

SH: When you were rounding up the buffalo were you doing that on horseback or with helicopter or?

Duane: No with helicopters and a little bit of … not ATV’s but Gerry Lyster had a little dirt bike. It was more of a teenager’s dirt bike and he looked silly riding it. But he’d be sashaying and chasing the buffalo down the chute with this bike, or going back and forth, coordinating between crews that are managing this gate or that gate. But the buffalo were brought in by helicopter.

SH: Interesting.

Duane: There was only one year left of that, and they stopped doing it. It was expensive, it was hard on the animals and park management was quite against it. There was also beginning to be push back from the native groups. The cruelty to the animals and the brutality of how we managed the bison, was harsh. especially the research on anthrax, bovine tuberculosis and brucellosis. Anyway, we had done a lot of alienation of the First Nations people, in and around the park. The treatment of buffalo, and the power of rationing the hunting opportunities and trapping opportunities made for a very tense relationship. But they were particularly upset with our handling of the buffalo.

SH: Wow. You’re the first person that I’ve interviewed that worked in Wood Buffalo so were you doing much fire management then Duane?

Duane: Fire management was a huge program and largely separate from the Warden Service. I think there was a couple of things with the Wood Buffalo fire management program. It was a significant employer, and the park still had active logging happening as well. So, the idea of protecting timber resources was still entrenched.

One of the things that is forgotten about Wood Buffalo National Park, is Wood Buffalo came under the Parks Canada’s management quite late in its history. It had been managed as a branch of the NWT government for the northern administration as it was. NWT became a self-governing territory I think in 1967. The capital had moved to Yellowknife but prior to that, the administrative capital had been Fort Smith. Wood Buffalo National Park was managed as an extension of the NWT government down into Alberta. So, they had logging, and a slaughterhouse at Sweet Grass, so there was this idea of modification and commercialization of resources in the north built right into the management vision, including for Wood Buffalo Park, because it was being managed by this northern administrative group focused on northern development.

Mrs. Ben Houle showing off Lynx pelts after tea and a visit to their trapline in the park. Circa 1978.

Duane, not sure if you will get this but here goes anyway. Just re-read your interview for the third time. One of the best in the alumni group for sure Not surprisingily,your narritive is very well structured , meaningful, touching and personal on many levels. Some of the old partners and pictures, congered up some chuckles and tears at the same moment. To the outside world we all grow old, but not to those who walked in and lived the warden fraternity. Stay well Duane..

P.S. on the eve of a signifgant solar esciplse tomorrow, I am reminded of the day of another similar eclipse in 1979 I think, where you and I were digging, burning and burying a smelly anthraxed bison near Horniday cabin. Sure fun……..