So, they had some really interesting ideas about what a national park was and then Parks Canada took over administration I think around 1968 and they inherited these timber berths that were legal, the slaughter program. The last slaughter was for buffalo burgers for Expo 67. They closed the abattoir, but Parks Canada inherited a history, because Wood Buffalo dates to 1927, of an industrial park. So, a lot of this resentment and the perceived abuse of animals…we had a policy that the only animal that could not be hunted by First Nations was buffalo. They were the reason for the park and they were sacred, but we treated them like beef. So, our own inconsistencies were catching up with us, in terms of our credibility. When we tried to talk about being guardians of the wild, to the locals.

SH: Wow that’s interesting. I just learned a whole bunch, Duane.

Duane: Wood Buffalo probably has the most fascinating history, in my opinion, of any park. It is the most complex and amazing park resource wise, but the forces at play…things that were happening, that was also when the effects of the Bennett Dam, and damming the Peace (River) was becoming known. Lake Athabasca dropped, flooding in the delta no longer occurred, so there were all kinds of ecological consequences that were coming into play. They were mysteries to some extent. The bison population was dropping, there had been a disastrous flood probably around 1970 that drowned a huge number of bison on the Peace Athabasca Delta, which was one of the initial consequences of the Bennet Dam construction. That was also the last great flood. The delta habitat started deteriorating because the floods weren’t maintaining it to the same extent. Plus, the fisheries were changing and so this was a lot of stress on the community of Fort Chipewyan. This was also when Fort McMurray started to ramp up and have a big influence in the region as well. It was a very exciting place.

Gardening in Fort Smith

So, from there, I had it in my mind that I was going to work from coast to coast. When I was working in the north they had a Staffing Priority policy, and you could, if you had three years in, you could apply for a move, a transfer, and you had a priority to any region. Most staff were interested in trying to get into the mountains. I decided I wanted to go to Atlantic Canada, because it was a now or never thing in my mind. If I didn’t do it when I was single, and young enough to make a mistake, and I fix it myself. So, there was a posting offered in Fundy (National Park) and Winston Smith was Superintendent. He had been operations manager at Prince Albert when I first started, so I knew him. We talked on the phone, and he said for a single person it’s way too remote. I’d been working in Wood Buffalo and this place was twelve miles from park headquarters so I convinced him that I wouldn’t go stir crazy at Wolf Lake, and I’d be up to it. I was moved to New Brunswick, to Wolfe Lake Station at the northwest entrance for three years. So I went from one of the largest parks to a small one. I remember Al Sturko saying I’d go crazy in what he called a postage stamp park, but I got there, and I loved it. All of a sudden you could really get to know a place. I was back to like walking in the bush at Prince Albert and knowing it like the back of my hand. Fundy was exotic enough, the coast, the marine, but also culturally, that I loved it. I also learned a lesson there that when I moved …. I moved. It was like the place I just left …. did I really work there or was that just a dream. I was always very centered in where I was.

So, Francois Millette, who I worked with in Wood Buffalo and Prince Albert had taken a job in Terra Nova. So, when I got to Fundy, the Human Resource person, Bev Crowston, she said “Why did you move here?” So I said, “Well I moved to be close to the Millettes.” And she said, “Where are they?” I said “Terra Nova”. She looked at me like I was absolutely crazy. She said, “Terra Nova isn’t near here!” I told her on my scale of things it is. She later ironically was able to flip that when she moved to Riding Mountain, and she told people she moved there to be closer to Duane West in Kluane.

So, Francois inspired me to make the move and then I’ll be damned if Paul Galbraith didn’t show up there as chief not long after I got there. The locals were really getting quite concerned about this …. If the northerners were taking over. But eventually they got used to us. We eventually convinced some of them to go west or go north as well.

SH: So, what were your duties in Fundy?

Duane: When Paul came, at first it was a lot of driving around at night, chasing the elusive local deer poacher. When they established Fundy, they took half of the village of Alma and condemned it. There was a river, and this area where the park headquarters was, and that had been in the day, a rural part of the village. They cleared out the people and made a golf course, a big French Norman style admin building. With a golf course and a nice big lawn, it was an epicenter for deer, so the locals came across the bridge and got a deer frequently, or they got the wardens active. They’d enjoy seeing us come chasing them. They would go back across the river in a split second. It was playing games, but when Paul Galbraith got there, he was Mr. Do It. He set up a law enforcement program that was quite targeted. We didn’t play games anymore, or we didn’t chase people around. So, there was a break in issue in cars at trailheads, so he went to the RCMP and we got a decoy car, and put a purse on the seat. They had set the decoy car up and the warden was in the woods watching, and they hadn’t even got back to the office yet when the car was broken into. They went flying up the road to stop this crime and they met the perps head on, on a gravel road. But they caught them, and then they took off, dragging, I think it was Paul, dragging him down the road a ways. He was trying to grab their keys and he had his arm in the window, and they drove him down the road a little ways, with his arm in the window. It was really quite dramatic. So targeted law enforcement and then we got involved, significantly in restoration, in three major ecological restoration projects; reintroducing peregrine falcon, reintroducing Atlantic salmon to the Wolfe River, and a pine marten program. Pine marten were being trapped in northern New Brunswick where their habitat was being logged so they were trying to re-establish them in protected areas. The forest of Fundy had evolved to the point that it was suitable habitat. So we had pine marten brought down from Northern New Brunswick and released in the park, to re-establish populations.

SH: That’s exciting.

Duane: It was very exciting. There was a lot going on. (Tape 37:06)

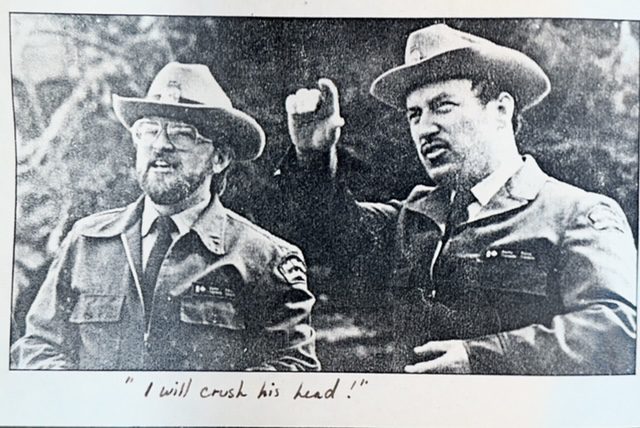

Duane West and Paul Galbraith, Fundy National Park, 1983.

I had wanted to work in Cape Breton. It was such a beautiful place, so I focused on that. I got the Assistant Chief’s job there, working for Al Gibbs. But it was Appealed, and the Appeal went on, and I won it again. They re-ran the competition, and I won it again. By the time I finally got there, it had been eight months or so, and it had kind of lost its charm.

Coincidentally right after I moved, there was an arsonist lose in Ingonish Beach. They burned down the highway station, so the plows and all the road maintenance equipment … they burnt all that down. Parks Canada golf course clubhouse was set on fire, and then Parks Canada had bought a property with an A frame on it. So, they decided to move this A Frame cottage over to the golf course to replace the burned down clubhouse. The arsonist torched it while it was still on the back of the moving truck. So, we had a burned down clubhouse, a torched moving truck, and A frame. Then they torched the parish hall, the church. So, waking up in the night to a major fire in the community, repeatedly, was disturbing to me. Cape Breton had historically a kind of violent undercurrent, that I had not been aware of. Some of it was old issues. George Mercer’s book touches on that a bit in “Dyed in the Green”. My whole Cape Breton experience, even though I worked for Al Gibbs who was great, had this kind of disappointment undertone to it for me, even though the park was amazing.

While my move there was uncertain because of the Appeals, Paul had left Fundy and was gone to Terra Nova and then on to Gros Morne. I applied on the Chief’s job in Fundy and to make a long story short, I got home from Sydney on a shopping trip and my firewood had been delivered. I suddenly had this “A-ha moment” where I went “Oh shit, I think I’m going to Fundy.” I went into the house and called Ken East, and he said “I was just going to call you. Yes, you did win the job.” So here I was with a load of winter’s firewood and I’m moving.

SH: So what year are we at here?

Duane: This was in 1983. I was only in Cape Breton for less than six months. It might have been as short as two and a half months. It was ridiculous.

So, I went back to Fundy as Chief. My career was in thirds roughly. I was a field warden for 10 years, a Chief for roughly 10 years and then I went on to miscellaneous senior appointments and Superintendent for the last ten years. I may have been the Chief, I may have been the acting Superintendent, but you weren’t allowed to call yourself that even if you were. So, I was back in Fundy and we continued on work on removing the Point Wolfe dam which was a scenic waterfall, but it was a barrier to Atlantic salmon spawning. So, we did that and the peregrine introduction was continuing on. So, I had three more years in Fundy and at that point I’d met and married Marguerite Richard. Then in 1986 we went to Jasper.

That’s where we crossed paths. So, two years as Assistant Chief, Resource Management in Jasper.

SH: So, what were some of your duties in Jasper Duane?

Duane: It was quite a dynamic time in Jasper because there had been the moving on of long-term managers. Duane Martin and Bob Haney had both moved on and Toni Klettl had retired. The stalwarts of the management team. I came in as an outsider and if I remember correctly, everybody else was still acting in their appointments. Marv Miller and Darro Stinson were acting and then Mike Briggs came almost at the same time as I did on a staffing priority at that level. He was going to be retrained for a Warden Service job. He had been in the Northern Fire and Forestry program out of Inuvik. It was a very dynamic time. I was resource management so that was safe ground, I had a nascent fire program starting up. Brian Wallace and Greg Fenton were doing the fire work. I had Wes Bradford who was the best intuitive wildlife manager the world has ever produced. He was looking after problem wildlife, and I had Gord Antoniuk working for me. It was an exciting time.

I had just read Alston Chase’s “Playing God in Yellowstone”. Working on the concept of ecological integrity on a greater park ecosystem. I can remember getting us to think outside of the boundaries, like the regional caribou issue. The mountain caribou was a major concern that we should be focusing on. I can remember being part of the screw up on opening up rafting on the Maligne and not knowing anything about harlequin ducks. That was brought to our attention rather abruptly. Introducing environmental assessments, working with Kurt Seele to get Jasper up to speed on environmental assessments. We just had just had bulldozers working in the Miette River for a month or so and nobody knowing about it. I had lots of fun in Jasper.

Then we began the business of reinventing government. I was assigned to the Management Information Framework Process, MIF. So, I spent a fair bit of time in Ottawa as well as traveling the country with the MIF team, and that was the beginning of the world of reorganizing and reinterpreting work. One of the dangers of the MIF thing was one of our case parks was Kluane. I went up there in August, and then a year later, the opportunity came, when the Chief’s position came open, it just thoroughly reminded me of a vow I had made back in 1976 when I went to Kluane on a vacation, was that if I ever had a chance of working there, I was going to take it without a second thought. I had a young son and a wife and managed to convince her that this was a great idea, so off we went to Kluane after two years in Jasper. That was way too short a time in Jasper. (Tape 50:18)

I remember you were one of our early visitors when we got there.

SH: Yes, you and Will and Sue Devlin were up there then. So, you moved up to Haines Junction then …

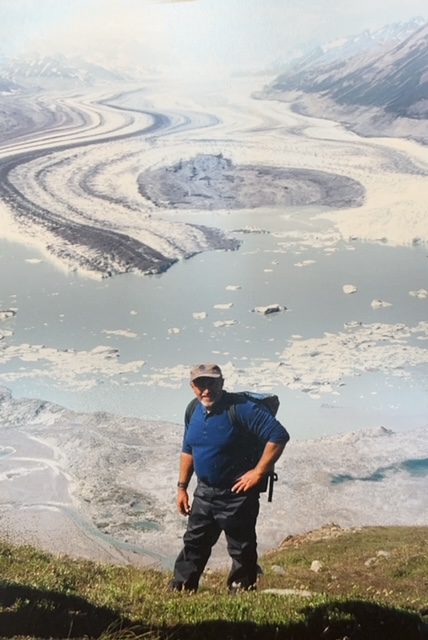

Goatherd Mountain, Kluane. It doesn’t get better than this!

Duane: Yes, I moved up to Haines Junction in 1988 and Phillipe was born in 1987 in Jasper. Right after he was born, I went up to Kluane on the MIF thing. We came home and landed in the Edmonton tornado. Our plane came in right during the tornado, and it was so violent, they wouldn’t let us deplane for a little while. Then we went through the jet way or whatever and it was just rocking. We got out and we heard the tornado had been at the other end of the city. It was all part of this weather system. The general works manager, Frank Leong, was on the team too, but his wife and Marguerite were both waiting at the Edmonton airport so it was more dramatic than necessary. Those things ensure you remember the trip.

So, we moved to Haines Junction. We went up via the Inside Passage on the Alaska State ferry system as the move … beautiful. We got into Kluane, and it was the summer that never came. It rained and was cold all summer and then late August transitioned into snow. Whose idea was this! But it was an amazing experience and an amazing park. It wound up capturing me for fifteen years.

SH: I remember you were Chief there and then you went into some big assignments or jobs?

Duane: I think the various things we went through …. When I went there, one of the things I was quite excited about was going to work for Charlie Zinkan. He was the Superintendent. We overlapped … I think I arrived in the beginning of July and Charlie and Marianne were out by mid-August. They went to Waterton. I remember that Charlie took me aside and said the Yukon land claims were going to become critical to the future of the park. He had been handling that file very close to himself. He gave me a marching charge. He said for this to succeed we have to get closer to the first nations community. If he gets invited to an event, he goes. Be involved in potlucks, funerals, community events and if you’re served gopher, eat gopher. I took those words to heart, and it ended up that in many cases I was the continuity on the land claim file, with the history in the negotiations. Superintendents changed …. Doug Stewart came in, but they didn’t end up letting him stay very long. He wound up going to Wood Buffalo to put out a fire there. A big part of my time when I was in Kluane, the land claims were interesting in that they were kind of off and on, hot and cold, but it was the big thing, Charlie had been dead on.

The park was literally on the table because it had been established so early and so brutally on the First Nations community from day one in the ‘20’s. It was part of the package for those communities of highway, park, residential school. It was all mixed. From the community’s perspective, enforcement is enforcement. They are here about your meat or your kids or whatever. What difference does it make? They are here taking something away. Great power and malice. So, there was a lot of resentment, but in Parks favor there is a core belief in protecting land and understanding that protecting land is essential for wildlife and culture from a First Nations perspective.

You could also turn them into allies if they understood that you were prepared to share management genuinely and see benefits from the Parks flow to the communities in a realistic way. Create workplaces that First Nations people could be comfortable in, and not your people and your culture versus a job … you had to give up one for the other …. we could respect that. That was my challenge and also a tremendous education. I got such privileged insights into the community and how it operated. The respect they had for the country, the knowledge they had of the country and the history tied to it, It was a beautiful exchange from my perspective. After I was in Calgary, I received a gift from the Kluane First Nation as part of being part of the land claim team. Their agreement was finished just as I was leaving. Great relationships were built at the table. It was one of the deeply privileged parts of my working for Parks for sure.

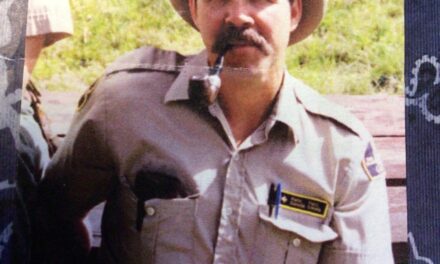

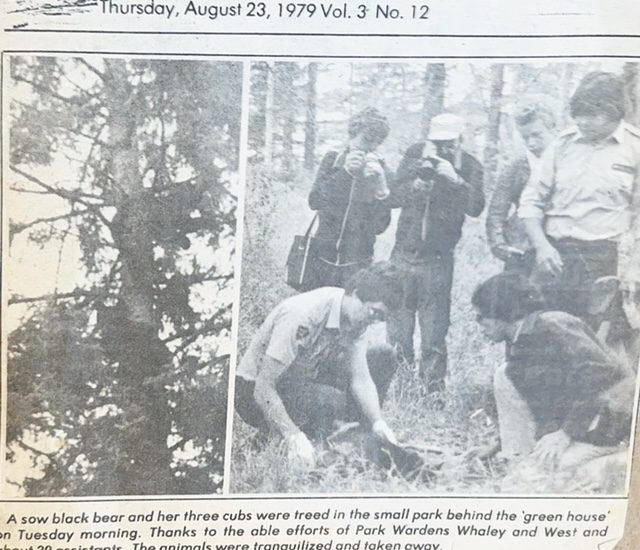

Slave River journal after we relocated a mother black bear and her 3 cubs out of downtown Fort Smith. Ray Whaley and Wesley Heron standing.

SH: You were incredibly good at that.

Duane: That led a little bit to Vuntut. I was the first person on the Vuntut, when Vuntut came through the land claims. Kluane was a pre-claims park that had to be negotiated to the claim, but Vuntut came out of the claim. It was the community of Old Crow. So, I was the first person whose salary was paid out of the Vuntut money, so I had a role in setting up the administration of how that park would be administered. We did a community planning exercise, for the impact and benefit plan and I managed that project. Then Bob Lewis took it over when it became more operational. Rhonda Markel was the first on the ground staff person for Parks Canada. We also brought trainees out of the community to Kluane, initially to train people, because we did not want to move Parks Canada people into the community first. We wanted the people in Old Crow, that there was somebody on the ground there, that was from there from day one. That worked out very well for Vuntut. The community had a sense of ownership and drive behind the park is there, but the Parks Canada presence is strong and valued. It was a great experience.

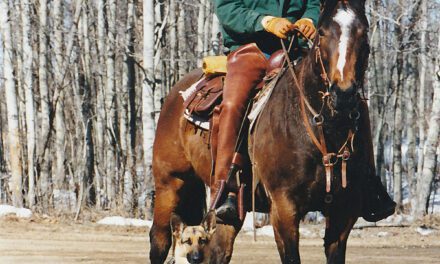

First Warden Patrol, Vuntut National Park 1998.

Old Crow is the only First Nations community that I’m aware of, that has never really had a true colonial experience. They didn’t have the big missionary influence. When the police went in, it was so brutal there, that they always had to have Vuntut Gwitchin people care for them. They made special constables and they would escort the police around, work with them one on one, to make sure they’d survive, because it is such a harsh environment. They’ve never lost that sense. It’s their country, they’re in charge, they work with the service providers, but they don’t take orders from them. For Parks it could have been a disaster to send the wrong person in there. It has worked out very well. That and Ivvavik were one of the first to come through the claims process and now, almost all across the country, if a claim doesn’t get a protected area, they are not happy. It has become a tremendous vehicle for establishment of Parks and conservation areas. (End of Part 2, Tape 1:03:44)

In 2003 I left Kluane and I was in the Western Canada office in Calgary and I was given an assignment to work on the how to translate … a Parks Canada approach to translating the benefits of claim established Parks to reality. So we were doing plans and strategies. I was working for Katherine Emmett. She was the Director for Northern Parks. We were doing plans and strategies around how they actually get the benefits in the agreements off the ground, around employment but also economic initiatives that would see benefits flow to communities.

I got exposed to what was going on with cruise ship traffic in Nunavut, which was a potential vehicle for visitors and benefits to Sirmilik and Auyuaitiq. I got to do a workshop in Churchill, and Katherine came too, which got me exposed to another park and region. It was a very exciting program out of Churchill. I was surprised how impressed I was with Churchill and Wapusk offerings. The beautiful job they did in turning the train station in Churchill into a Parks Canada Visitor Centre. Really elevating the offer there in terms of public appreciation and understanding of a very challenging site. Wapusk is hard to get to. Churchill, even at the fort has someone with a gun while they are giving the walks because a polar bear could be hiding behind a cannon.

SH: My daughter guides up there for Natural Habitat in the fall and says it’s pretty wild.

Duane: Oh, so she’s on the tours with the buses?

SH: Yes. She says it’s hard to convince clients at night that they need to take a cab back to the hotel from the restaurant because the bears are out.

Duane: I love the fact that in this country we have such challenging communities.

SH: What did you like about being a Warden? What didn’t you like about being a Warden?

Duane: What did I like about being a warden? Typically, at the end of the day that you could reflect on a day that you hadn’t anticipated when you started in the morning. Usually something came along and provided a distraction or an abrupt change in direction that required you to adapt to, because much of what we responded to was out of our control. It brought a sense of adventure to what you were doing and the challenge of responding and getting to reflect on it. I loved that.

What I liked least about being a warden was that we were instruments of dispossessing people at times. When I was at Fundy, it was the first time I realized the local people had a lot of grudges against the park and the wardens, representing the park … the long arm of the law. So, when I’d been working in Prince Albert and Wood Buffalo, and the locals had an axe to grind with the park, I always thought it was because as First Nations people they had been dispossessed from the park. But I realized it wasn’t specific to First Nations, it wasn’t a racial thing. People in Atlantic Canada, their experience with their land and homes being taken from them to create parks, was the same. It’s people whose identity is tied to place are really seriously disrupted when an arm of government or outsiders, or whatever you want to call it, come in and start telling them how things are. They supplant them as the custodians, owners of this place. It’s that conflict. But I also learned over time that we can shift and get comfortable trying to share the management of it, and not take it personally as well. Being an instrument of dispossession was my least favourite part of the work. That comes down to some aspects of controlling people, through law enforcement. Not everybody’s good time is appropriate in a park, and when you come up against somebody trying to have a good time, it is not a nice situation (Tape 7:46)

SH: What are some of the more memorable events of your Warden Service career or Parks Career?

I wrote a piece when I retired …. I wrote my best ten days working for Parks Canada, but when I finished it was fourteen days so I said I can’t count. I think it still stands. So, my best ten days working for Parks Canada and my worst ten days.

Note: I have inserted this piece here:

Today I am going to pack up my remaining personal items and the Staghorn Fern and walk out the door of the Parks Canada office at 635 8th Avenue Calgary. It has been a blast!

Right now listing is a rage: 101 Places To See Before You Die. The 10 Best Eco-Lodges in South Africa, 100 islands to Escape To, ad nauseum. Well, after casting a critical light on listing that is what I will do.